On the parched fields of Nir Oz, where children once roamed freely and neighbors lived as an extended family, silence now lingers. The kibbutz that for decades embodied warmth and community was now marked by loss and unanswered questions.

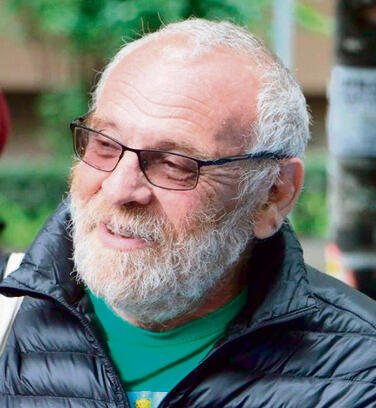

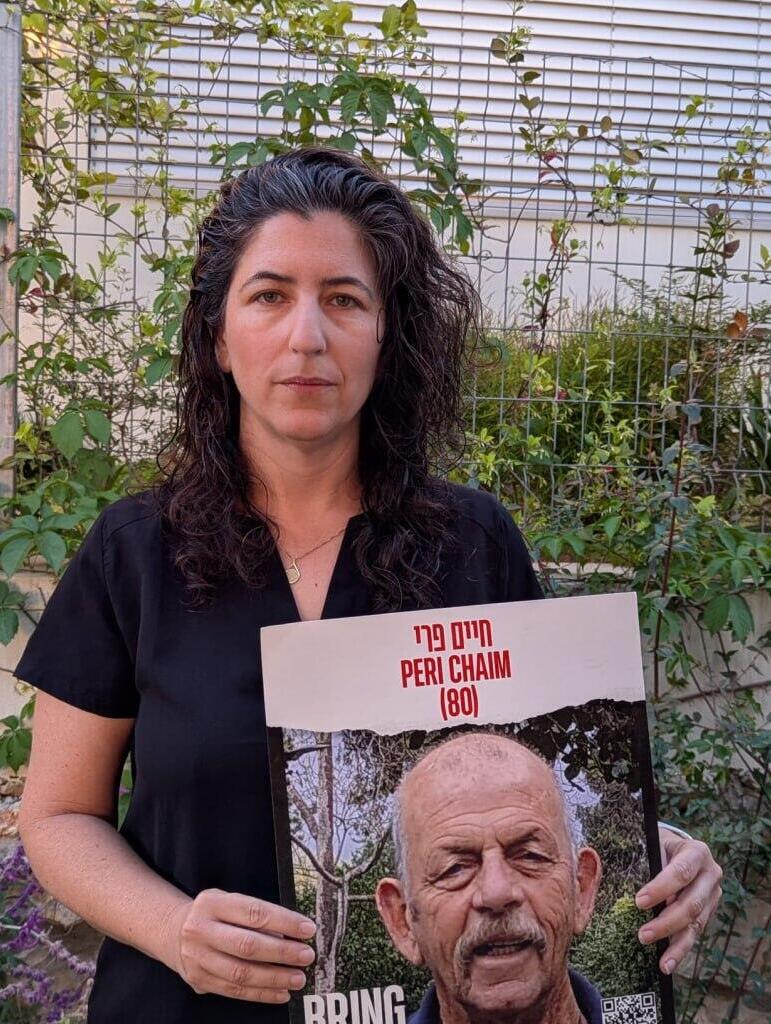

It has been a year since the bodies of Alexander Dancyg, 76; Avraham Mundar, 79; Yoram Metzger, 80; and Haim Peri, 80, were recovered from Khan Younis after being murdered in Hamas captivity. Their deaths, along with those of other elderly residents who were kidnapped from Nir Oz during the massacre of Oct. 7, symbolize a generation of founders who built the kibbutz and are no longer there to see it rebuilt.

“Metzger, Dancyg, Peri — they’re part of my childhood landscape,” said Rotem Cooper, 59, whose father, Amiram, was among those murdered. “The kibbutz was like a big family. We grew up together in the children’s houses, and every adult was in some way a parent. Alex was my history teacher. With Gadi Moses I worked in the metal shop. Munder was simply ‘Keren’s father.’ It was just family.”

Amiram, he recalled, was a man of culture and community leadership. “He was the secretary of the kibbutz, one of the initiators of the Nirlat paint factory. The kibbutz was his life’s work. But my father was abandoned twice: once when the borders weren’t protected, and again when he wasn’t brought home. Even Hamas didn’t believe the elderly would be left in captivity for months.”

For Rotem, the thought of expanding military operations in Gaza fills him with dread. “The moment the tanks rolled into Khan Younis, conditions for the hostages collapsed,” he said. “They were living on the ground, in tiny spaces, with barely any food or water. Talking now about conquering Gaza, while hostages are still there, is madness. If I knew my father was still alive and they decided to go ahead anyway, I couldn’t live with myself.”

Keren Mundar, 56, knows that pain firsthand. On Oct. 7, she lost her brother Roy, 50, while she, her parents Ruth and Avraham, and her son Ohad, then 9, were kidnapped. She, her mother and her son were freed in the first hostage deal, but her father was killed months later.

“I miss his loving gaze, his humor, his hugs,” she said quietly. “And I want to say I’m sorry. Sorry, I left him on the floor when we were taken, thinking they would show mercy. Sorry, he had to suffer 131 days of neglect and inhuman conditions. Sorry, he didn’t survive. Not because of him, but because of a government decision not to bring him home.”

For Noam Peri, 42, daughter of Haim, the sense of betrayal is just as sharp. “My father, Munder, Metzger, Moses — they were all part of the same founding group. They built this place, fought in every war. And then they were kidnapped from their homes, abandoned in captivity, and murdered. Except for Gadi, none came back alive.”

Decisions taken during the war, she said, left scars. “Military actions that knowingly endangered hostages were a black flag. We will hold decision-makers accountable. But what matters most now is saving those who are still alive. We can’t bring back the dead, but we can still save the living.”

For the children of Nir Oz’s founding generation, grief has become inseparable from urgency. They long for the return of remains, but even more so for the safe return of those still held. “One quarter of the people I knew were murdered or kidnapped,” Rotem said. “It’s unimaginable. I want my father’s body back, but more than that, I want the living to come home. As long as they’re there, that is the first duty.”

Keren’s words echo the same plea. “The most important thing now is to bring everyone back. No one left behind.” And as Noam put it: “For us, Nir Oz will never be the same. A whole generation of founders is gone. But I can’t grieve fully yet. The urgency to save those still alive is stronger than anything else.”