"I pledged to continue to strengthen dialogue with the Jewish people," wrote Pope Leo XIV, Robert Francis Prevost, in a letter sent last week to Rabbi Noam Marans of the American Jewish Committee. Today, this statement from the newly elected pope may sound almost self-evident but the relationship between the Catholic Church and the Jews has known very different days.

The Crusades, the Inquisition, the expulsion from Spain and blood libels are just some examples of Christian persecution of Jews in the past. The roots of this persecution go back to the figure of Judas Iscariot, who, according to the New Testament, betrayed Jesus and handed him over to the Romans.

However, over the years — especially in the second half of the 20th century — there were dramatic changes in how the Catholic Church leadership viewed Judaism and the Jewish people. Pope Leo XIV's words indicate that even the recent diplomatic tension between the Vatican and Israel, due to comments made by the late Pope Francis regarding the war in the Gaza Strip, does not negate these changes.

Father Alberto Joan Pari has been in Israel for 18 years. A friar of the Franciscan Order — which was entrusted with the custodianship of Christianity’s holy sites in the Holy Land 800 years ago — he meets with all communities.

In his role as secretary to the Custos (the Custos is the head of the Custody) and especially as the official responsible for interfaith dialogue in the Church in Israel, he sees it all: the complexities, the challenges but also the dialogue and hope for change.

"I've been responsible for interfaith dialogue for over 12 years," he says. "When I started, there were just a few isolated projects — groups of Israelis who wanted to learn a bit about Christianity and came to visit.

“That was the basis for dialogue and we worked hard to expand it. Today, 900,000 people visit us every year — especially young people after high school and before military service but also students and retirees."

What's the purpose of interfaith dialogue?

"To meet and tear down the walls between us, the stigmas that exist. A prime example is the cooperation we started 10 years ago with a synagogue — the Zion community in Jerusalem, led by Rabbi Tamar Elad-Appelbaum.

For a decade now, we've been jointly studying the weekly Torah portion with the synagogue's community. Together, Hebrew-speaking Jews and Christians study midrashim of the great rabbis and Church fathers and now we’re also studying Psalms together."

The turning points of the 20th century

A major turning point in the Church’s attitude toward Jews came with the conclusion of the Second Vatican Council in 1965, when the declaration Nostra Aetate ("In Our Time") was read — on the Church’s relation to non-Christian religions. This historic statement absolved the Jews of the charge of killing Jesus and called for an end to antisemitic persecution.

"I grew up after the Second Vatican Council, which was the turning point in Christianity’s position toward Judaism," says Father Pari. "At the Council, the Church corrected its theology and its understanding of the relationship between Christians and Jews. After the Second Vatican Council, we said: we were wrong — the Jews aren't responsible for Jesus' death, neither that generation nor those that followed.

“This brought about a tremendous change: before the Council, Christians thought the Jews were to blame, that they were the reason we couldn't reach salvation. After the Council, we came to understand our mistake and said: sorry, the Jews can reach salvation in their own way."

Father Pari explains that "the only Gospel in the New Testament that clearly points to Jews as being guilty of anything is the Gospel of John. It was written shortly after an important meeting in Yavne. All the heads of Judaism gathered and decided that Jews who believed Jesus was the Messiah could not participate in their communities and had to leave synagogues and congregations.

“So John testified that the Jews were against the Messiah and had done such and such. From there came the Church’s view that the Jews didn’t believe in the Messiah and were therefore guilty — not part of God’s community and forever condemned to pay for it.

“But there’s no clear theology behind that. The only direct link people make is to Judas Iscariot — but even that’s not valid. Today’s theology says: the Messiah had to go through death, so you can’t blame the Jews for handing him over to the Romans. It had to happen."

The Holocaust was one of the central events that influenced changes in the relationship between Catholicism and Judaism. Though many Jews were hidden in monasteries and churches during the Holocaust, some historians accused Pope Pius XII of remaining silent in the face of atrocities and failing to use his power and status to help save Jews.

According to Father Pari, "Before the Holocaust, there had never been such a profound event that shook the population and so it wasn't possible to create meaningful connections that could lead to a shift in perception. After the Holocaust, questions arose within the Church: are we responsible? Did we have a part in this? That event opened the door for reflection and action."

‘We also need to let go’

During the war between Israel and Hamas, former Pope Francis accused the IDF of brutality. He claimed that Israel was " machine-gunning children" in Gaza and spoke of "bombings of schools and hospitals" — without mentioning the evidence that Hamas terrorists were operating from those same institutions.

Against this backdrop, Israel didn’t send a senior official representative to the Pope’s funeral — a decision that drew heavy criticism.

"The feeling of victimhood — of seeing oneself as a victim — can become a self-fulfilling prophecy," warns Rabbi Yakov Nagen, head of the Ohr Torah Interfaith Center, part of the Ohr Torah Stone network.

"We’re in a global event and an event like this requires cooperation with other nations and religions. To give up in advance and say 'everyone’s against us,' to be a 'people that dwells alone' — that’s not how we’ll get through this. 'Together we’ll win' means forming alliances and we have to understand that."

He adds: "God willing, the new pope, who comes from Chicago — a city with a large Jewish community — will continue the process of interfaith dialogue and reconciliation. It's important to say that part of this process is that we, too, need to let go.

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

“There's an ugly phenomenon of spitting on Christians in Israel. If we stay stuck in the pain of the past — we won't build a different future. Yes, we have trauma but we want to build something better."

As for the late pope's attitude toward Jews, Rabbi Nagen notes that in a letter to Dr. Eugenio Scalfari, Francis wrote: "God has never abandoned His faithfulness to the covenant with Israel and through the terrible trials of recent centuries, the Jews have maintained their faith in God — for which we, the Church and the entire human family, can never thank them enough."

"He had a tendency toward pacifism and I don’t think he had anything personal against the Jewish people but I don’t intend to excuse it," Rabbi Nagen says about Francis's one-sided statements on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. "It’s just important to remember that even if there were a few outrageous remarks at the end of Francis’s life, we’re in a completely different place now."

According to him, "It was a process. In the past, there was a widespread accusation that the Jews were guilty of Jesus’s murder and cursed for all generations and that led to endless Jewish bloodshed. There was also a belief that we were wandering the world because we were cursed."

That connects to the “wandering Jew” myth.

"Yes. There were also formal prayers in the Church calling for the conversion of the treacherous Jews who would accept Jesus. In 1965, Nostra Aetate called out against antisemitism. Another dramatic change happened under Pope John Paul II.

“He led the way to recognition of the State of Israel. It must be understood — this was a massive upheaval. A founding myth of Christianity was that the Jews were punished with wandering because they didn’t recognize Jesus."

How do Christians explain the success of the State of Israel and Zionism?

“In Protestant Christianity, there’s long been talk of the return to Zion as a positive process, a sign that the Messiah’s return is on the way — especially among evangelicals.

“In Catholicism, after dropping the claim that the Jews are cursed — recognizing it as a distorted interpretation not based in Christian sources — there’s been a renewed acknowledgment that Jesus was, after all, Jewish, as were all his disciples.

“The Bible still speaks of the return to Zion. Once the theological block to acknowledging the Jewish connection to the land was removed, recognizing the State of Israel became possible.”

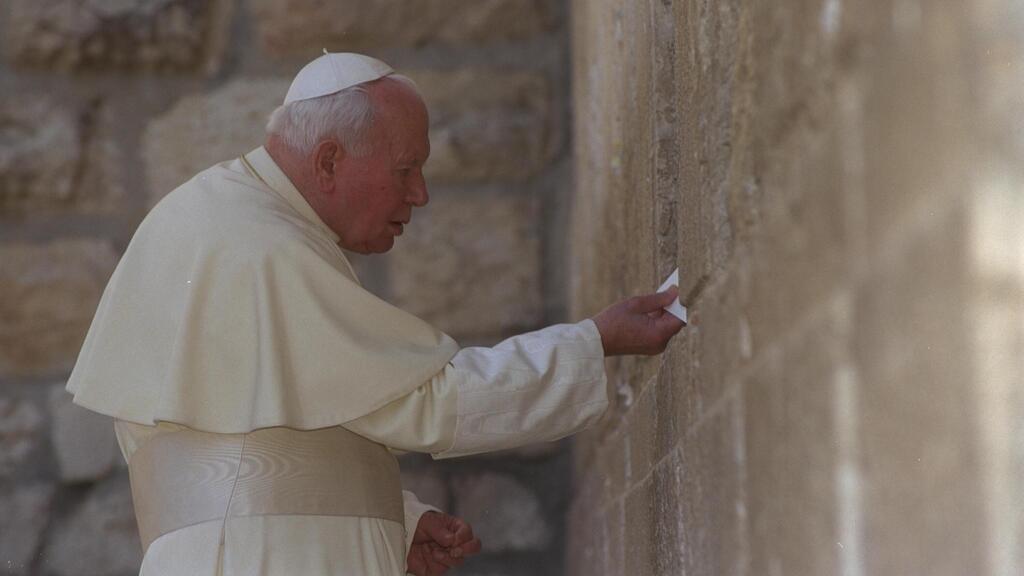

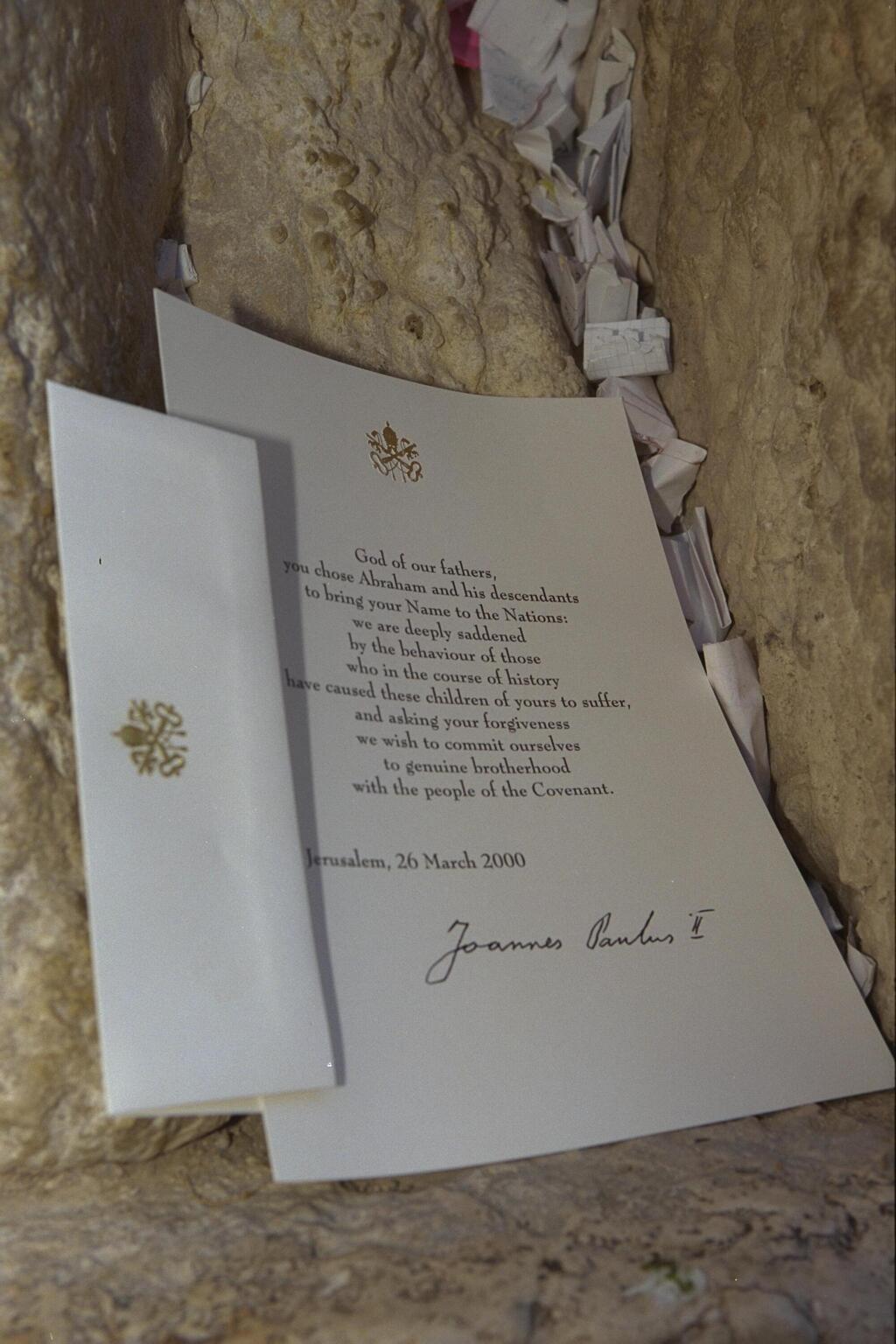

Pope John Paul II not only recognized the State of Israel but also referred to Judaism as Christianity’s “older sister.” During his visit to the Western Wall on March 26, 2000, he placed a note between the stones asking forgiveness for the Church’s past persecution of Jews.

The note, now preserved at Yad Vashem, read: “God of our fathers, You chose Abraham and his descendants to bring Your name to the nations. We are deeply saddened by the behavior of those who in the course of history have caused these children of Yours to suffer and we ask Your forgiveness. We wish to commit ourselves to genuine brotherhood with the people of the Covenant.”

The impact of October 7

During the war, Rabbi Nagen met with delegations of Christian clergy from abroad. “In one case, I met Christian leaders from Africa who had come to express solidarity with Israel after October 7,” he recalled.

“The Foreign Ministry brought me and Rachel Goldberg-Polin, Hersh’s mother, to meet with them. She spoke about Hersh’s abduction and began crying. Since these were Christians well-versed in the Bible, I told them: ‘Gentlemen, in the Book of Jeremiah it says, Rachel weeps for her children, refusing to be comforted… they will return from the land of the enemy.

“This isn’t a thing of the past, it’s the present. Right before your eyes — Rachel is weeping for her children.’ They started crying too.”

“I spoke with a leading Christian figure from Nigeria and he told me: ‘Every month in our country, Boko Haram terrorists commit atrocities like October 7 but no one counts us, no one sees us.’

“People need to understand that the world’s obsession with the Jewish people is just that — an obsession. It manifests in hatred, yes but also in other ways. Who in the world doesn’t know about the Israeli hostages? But how many people know that 2,000 Yazidi women are still being held as sex slaves by ISIS?”

How can the lessons from Christian-Jewish reconciliation be applied to Jewish-Muslim relations?

“That’s already happening — we’re in motion. It was expressed, among other things, in the Abraham Accords. Theologically, it’s much simpler with Muslims: they too believe in one perfect God and historically, there’s less baggage.

“The Jewish side can offer respect and warmth toward Muslim faith and religious life. A lot of work is needed on personal relationships — building mutual respect, a two-way street — with the goal of identity serving as a bridge, not a battleground.”

When Father Alberto Johan Pari is asked to assess current Christian-Jewish relations in Israel, he responds: “Before October 7, the relationship was mostly good — especially between the Vatican and Israel. There was real dialogue, also between Christians and Jews more broadly.

“There were some incidents of spitting at clergy in Israel, especially in Jerusalem and that went a little too fat. It’s a small group of Jews who do it — it’s unclear what motivates them — but it’s one specific community.”

“October 7 changed things dramatically. The pope’s words were very delicate. When he spoke against the terrorists, it was fine. When he supported the hostages, that too was fine. But when he expressed concern for the humanitarian situation, people thought he was siding with Hamas. Politically, the situation is very sensitive now. But there’s a new pope and his first words were about peace, interfaith dialogue and building bridges between nations.”

Are Christians in Israel troubled by how Jewish society treats them?

“I can’t speak for everyone, of course. I’m a Christian, an Italian clergyman living within Israeli society. I work with a community of Hebrew-speaking Catholics who are all Israelis but most of the local Christians in Israel are of Arab descent. It’s a very complicated issue.

“From the Arab Catholic communities, I understand they’re feeling uncomfortable these days — because of their Arab identity. Politically, they’re Israeli but in their faith or in their hearts, many are Palestinian Arabs. It’s part of a bigger question — what does it mean to be a Christian in a country with a Jewish and Muslim majority?”

He continues, “What all religious leaders are trying to say is that the role of Christians is to be in the middle. We have to help the different communities in this country, to create dialogue, to promote coexistence.

“To learn together, to work together, to live together in one state. That’s a very Catholic idea — we’re an international church, without borders. So our role is a bit more ‘free’ — to build bridges.”

Were you disappointed that Pierbattista Pizzaballa, the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem and the first cardinal from Israel, wasn’t chosen as pope?

Father Pari laughs. “We had high hopes. We could’ve only benefited if he had been chosen. A pope from here understands the situation in this country, in the Middle East and in our community.

“We were certain he could’ve continued dealing with the Israeli-Palestinian issue, Jerusalem, choosing the right person to head the Franciscan order, the next patriarch of Jerusalem. But now that he’s back here — that too is a blessing, so we’re happy either way.”