Daniel and Neta live near the Central Bus Station in south Tel Aviv—in a home that has a reinforced shelter. But following recent damage to shelters in cities like Petah Tikva, they began looking for a safer option. That search led them to the station’s long-forgotten atomic bomb shelter—an enormous but badly neglected facility.

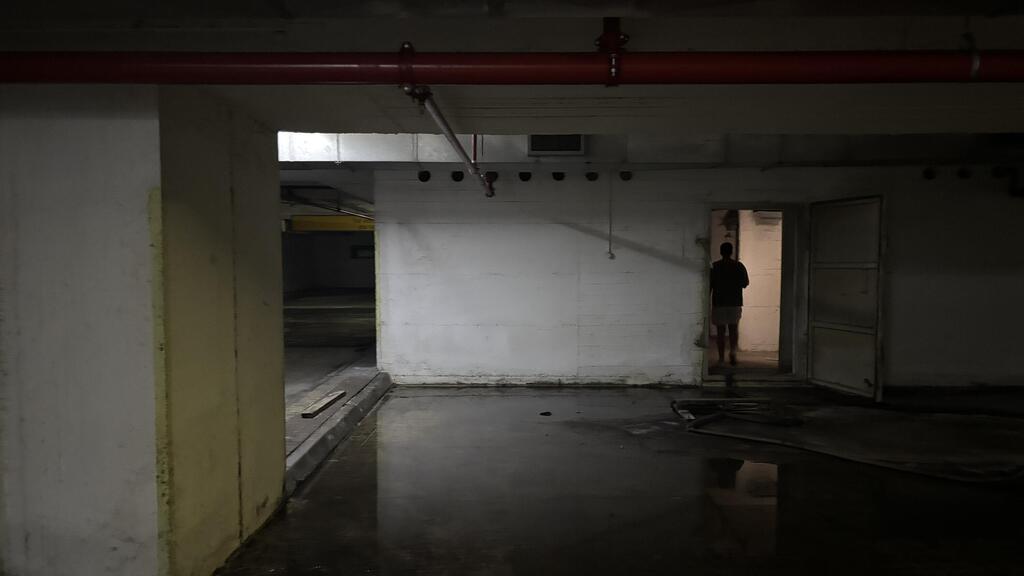

“The Central Bus Station is fascinating,” they said. “We knew there was a huge nuclear-proof shelter here but it doesn't seem livable.” The shelter includes decontamination chambers, toilets, showers, changing rooms, water tanks, a massive vault and heavy red blast doors—all now hidden behind decay.

“I came to see if I could sleep here at night, but in this condition, there's no chance,” said Sapir, another resident of south Tel Aviv, who’s been urging the city to address the state of public shelters.

“Some shelters are closed off, even when sirens sound. A few days ago, I asked why a school shelter was locked and was told they feared looting. I understand the concern but you could remove valuables or open it only during alerts. Keeping it shut isn’t acceptable.”

Sapir added that many residents of south Tel Aviv—both long-time locals and asylum seekers—are from low-income communities, often without access to home shelters. “Unlike more affluent location in Tel Aviv, which have games in their shelters, here it’s pitch black, filthy and stinking of sewage. There are wooden pallets so people can avoid stepping in feces. Why is this acceptable?”

Others have given up on the shelter altogether. Menachem, who sells electronics in the station, said: “I haven’t gone down there. Just look at the stairwell—who knows what it’s like down there?” Outside, taxi drivers echoed the sentiment: “We’re not going down there during a siren.”

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

Access to the shelter is confusing. Even if you follow the signs and descend three levels, you’ll find a locked door. “By chance we saw an emergency door labeled 37/1. Someone was there and didn’t want to let us in, though we’re not sure what his role was,” Daniel and Neta recalled.

“We went down several more levels and finally reached the shelter.” Sapir added, “Even the Hebrew signs aren’t clear. People panic during sirens—why should they be met with locked doors? There should be signs in all relevant languages: Hebrew, English, Arabic, Amharic and Tigrinya.”

In response, the Tel Aviv Municipality said it had opened all public shelters across the city, upgraded signage and added large underground parking lots as additional protected spaces in coordination with the IDF Home Front Command.

Hundreds of shelters in schools, welfare centers and community buildings have also been inspected, with over 600 reinforced spaces now available to the public, all meeting national safety standards.

Due to the citywide shortage of proper shelters, Tel Aviv and the Home Front Command have added approximately 90 new public shelters since the war began. In recent days, the Central Bus Station shelter was reopened after a thorough cleaning conducted by station management in coordination with the city.

The municipality clarified that while the shelter is now operational, its maintenance is the responsibility of the bus station’s management company.