Contrary to popular belief, tipping is not an effective incentive to improve service, according to a new study. Researchers found that because most people tip out of conformity rather than appreciation, waiters expect to receive tips regardless, which weakens their motivation to put in extra effort. As a result, the quality of service doesn’t necessarily improve, while the pressure to conform may cause tip rates to keep rising.

The study, published in the journal Management Science, was conducted by Dr. Ran Snitkovsky of Tel Aviv University’s Coller School of Management and Professor Laurence Debo of Dartmouth College’s Tuck School of Business. It explores the logic behind tipping — or the lack thereof.

The researchers focused on two main motivations for tipping: genuine appreciation for service and social conformity. Those who truly value good service tend to tip above average, while conformists simply follow their lead. In societies where tipping is a social norm, this dynamic drives average tip rates upward over time.

“Tipping is a phenomenon that’s difficult to explain using classical economic tools,” Dr. Snitkovsky explained. “For the purely economic person who seeks only material benefit, there’s no reason to tip after the service is already received. Some theories suggest tipping secures better service in the future, but that doesn’t explain why people tip even when they know they’ll never return. Another argument claims tipping motivates better service — but if I’m rational, it’s better for others to tip to keep service levels high, while I save my own money. So we need to consider behavioral and psychological factors to fully understand this phenomenon.”

A recent USA Today report found that the average American spends nearly $500 a year on restaurant and bar tips, with the tipping system generating over $50 billion annually in the U.S. — a major source of income for millions of servers.

“We used a mathematical model and tools from game theory and behavioral economics to analyze what drives tipping,” Dr. Snitkovsky said. “We looked at two key motivations: gratitude toward the service provider and the feeling that ‘this is what everyone does.’ In other words, there are appreciators and conformists.”

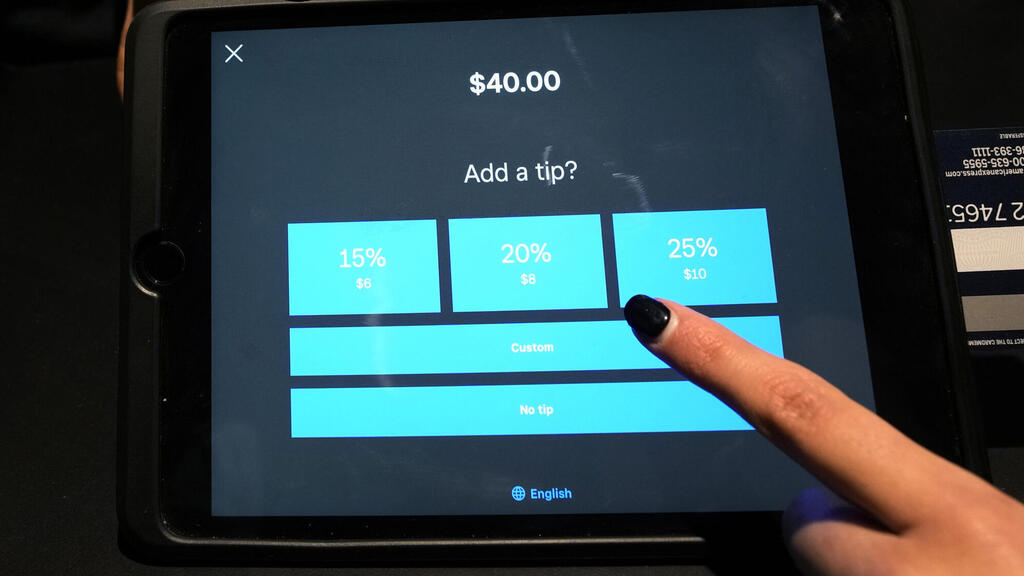

The study found that in societies with stronger social norms, where people feel a greater need to act like others, average tip amounts rise over time. “The process naturally pulls the average upward,” Dr. Snitkovsky explained. “In the 1950s, tipping in the U.S. averaged around 5 percent. Today, it’s closer to 20 percent. Appreciators lead by tipping higher, and conformists follow to avoid deviating from the norm. The widening income gap might also play a role in this rise — an idea supported by our model and suggested by Professor Yoram Margalioth of Tel Aviv University’s law faculty.”

Another question the researchers examined was whether tipping effectively motivates service providers themselves. The model shows that tips can be an incentive — but a weak one. Since many customers are conformists who will tip regardless, waiters have little reason to make a special effort. “If a waiter knows most customers will tip the standard rate anyway, there’s no real incentive to go above and beyond,” Snitkovsky said.

He admits his own bias: “I hate tipping,” he confessed. “I came to this research not entirely neutral. Personally, I dislike the practice, which is why I wanted to understand it better. Tipping puts the customer in an awkward position. Studies show it encourages sexist behavior toward waitresses, who may feel pressured not to set boundaries to avoid losing tips. There’s also evidence people tend to tip more to servers of their own ethnicity, introducing a racial element. There are plenty of reasons to abolish tipping — but it has positive effects, too, which makes it a complex issue.”

“In the end,” he concluded, “it’s a system where those willing to pay more effectively subsidize service for those who pay less, which isn’t entirely bad. Tips do have a small effect on whether a waiter decides to provide good service. But in the 21st century, business owners have better tools to measure performance — online ratings, for example, or even in-store cameras.”