On June 13, in the early morning, a new Israeli satellite named RUNNER 1 was launched from the Vandenberg U.S. Space Force Base in California. The satellite, which was launched aboard a rocket by Elon Musk's SpaceX, weighs less than 90 kg (200 lbs). This marks the beginning of an exceptional project led by Chile and the Israeli satellite company ISI (ImageSat) from Or Yehuda, which is controlled by the FIMI fund.

Read more:

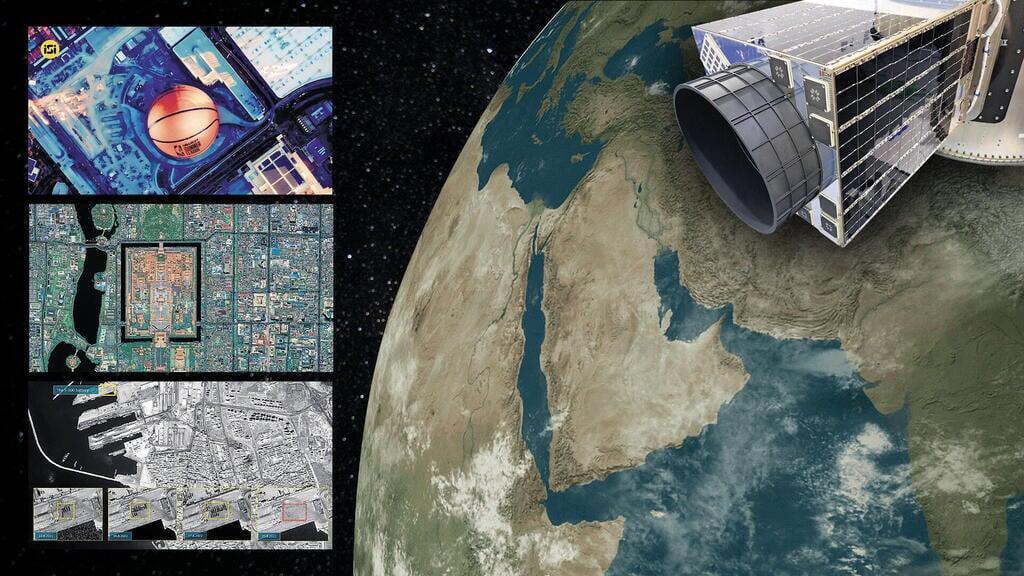

While satellite imaging capabilities were exclusive to major powers until the early 2000s, today, in theory, anyone can purchase satellite images. ISI, known for its "before/after" satellite images that appear following natural disasters or after Israeli Air Force strikes, was among the first to provide access to such images for commercial uses.

Today, it's one of only four civilian companies worldwide with the capability to provide particularly high-quality satellite reconnaissance. Two of them, the American Maxar and the European Airbus, are its direct competitors. The latest addition to this list is China's CGST.

The Runner and its counterparts exemplify the dramatic changes that have taken place in modern satellites over the past decade: from massive military reconnaissance satellites – for instance, the largest imaging satellite of the U.S. military weighs 16 tons – that orbit at high altitudes and whose existence is sometimes kept secret, to compact satellites equipped with sensors across various domains and sizes, orbiting at relatively low altitudes and serving a variety of civilian purposes.

"Today," says Shlomo Indy, 53, VP of Space Programs at ISI and head of the company's development group, "a simple farmer can mark his plot on a satellite image using a phone or tablet, specify that he's growing avocados or blueberries, and a computerized system, based on the satellite's images and data, will precisely determine where and how much water he should use for irrigation."

Space as an educational springboard

Chile, with its 20 million residents, is considered one of the fastest developing countries in South America and boasts some of the world's most advanced communication infrastructures. It was among the first to roll out 5G networks, and optical fibers reach over 90% of its population. The nation has also maintained an independent space satellite for years.

According to Indy, who oversees the Chilean project for ISI, "The Chileans made a fundamental decision: they want to nurture a new generation that isn't intimidated by technology, and they see space as a springboard for that. While our direct client there is technically the Air Force, in practice, it's a civilian initiative."

Three years ago, Chilean President Sebastián Piñera announced an ambitious space project with an initial $110 million investment. Around this, Chile has built numerous sub-projects in various fields, some of which have already begun implementation: promoting technological education, satellite communications, modernizing agricultural processing methods, establishing a weather alert system, more efficient handling of fires, floods and security events, and of course, a boost in the intelligence available to their military and internal security forces.

ISI is spearheading this project, having been selected as the main contractor for the program from 45 global contenders. The Runner 1, a mini-satellite, is leading the charge in this endeavor. It's the world's first imaging satellite with an optical system—meaning a combination of camera and telescope—designed from the start to also capture video in full color. It's positioned at a relatively low altitude of about 340 miles, orbiting the Earth.

ISI, which developed it (and had it built by the American company Tyvak), is expected to launch two more similar mini-satellites in the next couple of years. All three will augment Chile's existing satellite in space.

Later on, seven more tiny microsatellites will be launched, each with a diameter of roughly 12 inches and weighing 25-30 pounds. Interestingly, some of these will be constructed in Chile itself. All ten satellites will be launched aboard SpaceX rockets.

Of course, satellites are accompanied by ground stations – an extensive system rich in computing and artificial intelligence, established by the Chilean government in collaboration with ISI.

A new national space center called CEN opened last year in the city of Serillos. From there, as well as other centers in the cities of Santiago, Albuska, and Pedual, commands are sent to the satellites, and the downloading, collection and analysis of the images and data they provide are executed.

The centers will feature laboratories established by Imagesat for assembling satellites and their payloads (mainly cameras and various sensors), a space mission control center, a center for analyzing geospatial data (including that from drones and UAVs), and also a center for entrepreneurship and innovation. They are also developing specialized apps with a user-friendly interface for government workers who are expected to use the collected information.

Recently in Chile, training sessions have been initiated by ISI engineers. Chilean engineers there are learning about satellite system design, image processing and more. By the end of the year, company experts, reinforced by specialists and scientists from Israeli academia, will begin teaching lessons in high schools and academic courses at Santa Maria University in Santiago.

As part of the collaboration, engineers from the Chilean Air Force arrived in Israel in recent days. They will be trained in Israel over the next year in satellite assembly processes and satellite integration.

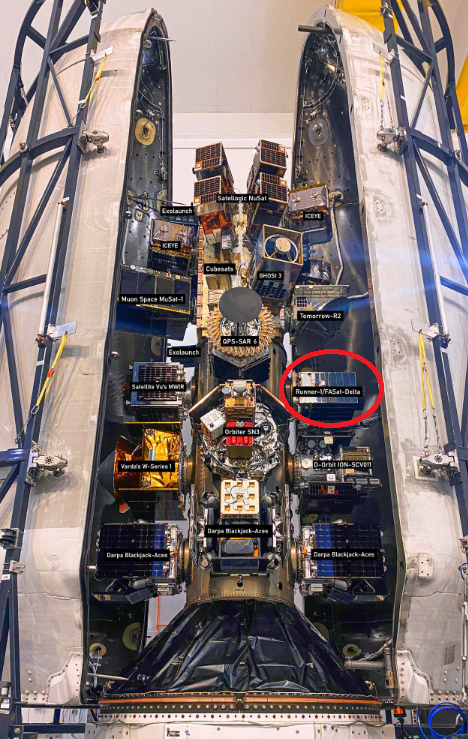

The 200th successful landing of a SpaceX launcher, after the launch of satellites, including Runner 1

(Video: SpaceX)

With the assistance of Israel's Ramon Foundation, which specializes in developing advanced educational programs on aviation and space in Israel, ISI has completed a special curriculum for the Chileans called SpaceLab. Initially, this program is being implemented in 23 schools across the country; much like the Beresheet spacecraft project in Israel, which served as a catalyst for extensive educational activities to promote interest in space research.

Assuming the final tests conclude as expected, the company will provide Chile with a solution this month that enables impressive satellite communication coverage. While satellite communication is expensive, it's a good option for people living in remote areas or those not connected to conventional communication infrastructure. It's also essential for medical emergency systems, military and security operations.

Satellites by the pound

According to ISI CEO Noam Segal, 55, mini-satellites like Runner 1 and the new micro-satellites are part of the "New Space" trend, which began about 14 years ago as a student's final project. Two professors, one from Stanford and the other from the California Institute of Technology, introduced the CubeSat concept — essentially a container loaded with small satellites.

This container can be attached to a large launch rocket, effectively "hitching a ride." When the rocket reaches the appropriate altitude, it "deploys" them into space, significantly reducing launch costs. The idea took off, and launch companies began accepting satellites for launch at a rate of "$20,000 per kilogram." Launch costs can indeed be steep: launching an EROS-type satellite, for instance, costs around $60 million, while the satellite itself costs about $130 million.

Granted, the imaging capabilities of these satellites are more modest than those of the traditional giant satellites, and their lifespan is limited due to the harsh radiation conditions in space — only 3-5 years compared to the 20 years that older satellites can last. However, they serve as an excellent complementary solution.

According to ISI CTO Doron Shterman, 37, before the "New Space" era there were only about 1,000 satellites in space, today there are around 10,000. By 2030, this number is expected to reach tens of thousands.

Shterman says color imaging opens up new areas for satellite services, such as mapping, agriculture and monitoring the Earth's climate. Color satellite imagery can quickly identify diseases attacking crop fields or pollution in the ocean waters.

On the other hand, it provides a lower resolution than black-and-white images and also requires the installation of more advanced equipment on the satellite. ISI takes pride in the fact that, for example, Runner 1 delivers color resolution close to what it provides in black and white (about 27.5 inches per pixel).

7 View gallery

The satellites that were launched into space in June on the spaceX launcher, the Israeli satellite is surrounded by a red circle

(Photo: SpaceX)

ISI, originally established by Israeli Aerospace Industries (IAI), only began developing its own satellites about 5 years ago and is now valued at about NIS 704 million ($183 million). Out of its 90 employees, 30 primarily focus on the design of these small and lightweight satellites.

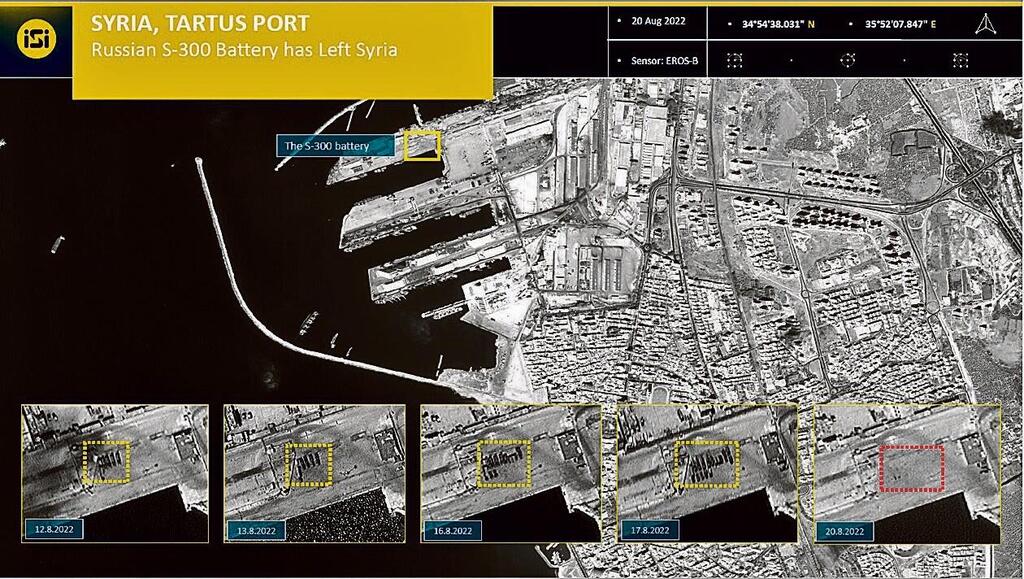

However, the company's crowning achievement comes from the ownership of the three large EROS satellites, which were manufactured for ISI by IAI. The first two were originally developed as the civilian counterparts to the military imaging satellites from the Ofek series, with the intention of selling the satellite capabilities on the international market without exposing them. In practice, following the launch failures of Ofek 4 and Ofek 6, both EROS A and EROS B ended up serving the defense establishment as military satellites.

The latest representative of the EROS capabilities, currently a global top-tier, is the EROS C3" This satellite was also constructed by IAI, launched just about 8 months ago, and last week it has already transmitted its first breathtaking, full-color images at maximum resolution.

It's one of the most advanced civilian observation satellites in the world, capable of capturing images with an impressively high resolution of 30 centimeters (12 inches) per pixel (meaning each pixel represents a 30 cm square on the ground). It can operate even in challenging lighting conditions and can capture images across multiple channels simultaneously. The C3 can scan up to about 600 kilometers (370 miles) in a single sweep and deliver dozens of images in roughly 10 minutes. It's also among the few satellites globally that allow for real-time imaging and immediate image downloading – a particularly vital feature for security incidents and natural disasters.

7 View gallery

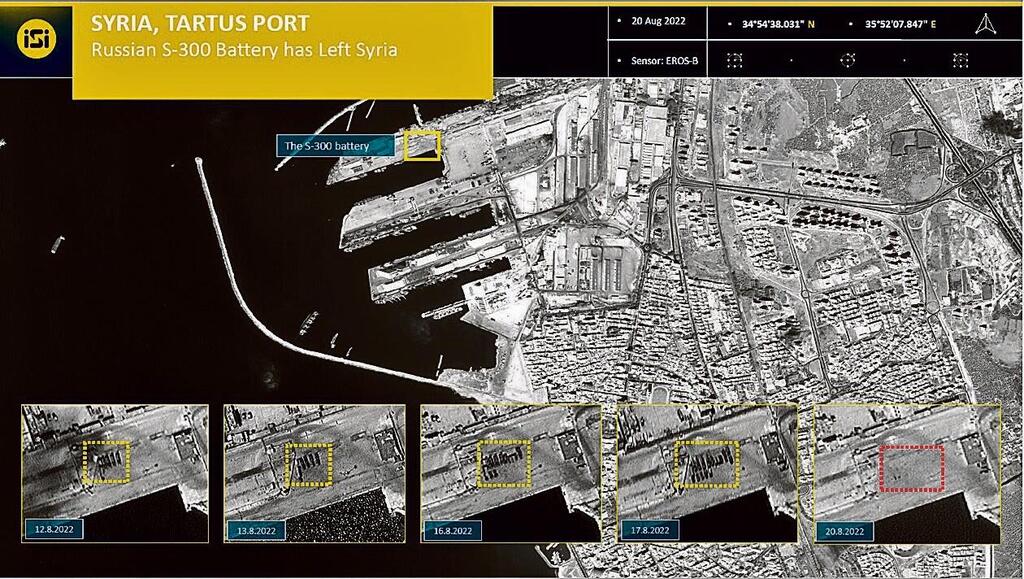

Tartus Port in Syria in 2022, before and after the Russian S-300 batteries were removed from it

(Photo: ISI)

Commercially, it's especially cost-effective since it can serve both civilian and security users at the same time. While typically, color satellite images are 4 times lower in quality than black-and-white ones, with EROS C3, the color images are only 2 times worse in quality.

A single image from such a satellite covers a massive area of about 10 km by 10 km. From this, the desired area is "extracted" for enlargement. This way, thanks to repeated images, it's even possible to reconstruct floor plans of buildings based on sequential shots of their construction stages.

A look into the future

Shterman has been involved in satellites since his military service. He has been with ISI for 7 years, and concurrently is completing a Ph.D. in electrical engineering at the Technion.

What sets Israeli satellites apart?

"Firstly, they're very small compared to their competitors. EROS C3 weighs only 880 pounds, while the comparable American/European satellite weighs 2 tons. The reason is simple: constraints. Our launcher simply can't 'lift' heavier satellites. But the advantages are clear — agility and the ability to shoot video — meaning a lot of consecutive images, up to 30 frames per second. We not only know how to extract intelligence from an image but also how to plan the act of shooting optimally to obtain the precise information required."

"A satellite in low orbit moves relatively quickly and circles the Earth every 90 minutes. This means it only hovers over a shooting area for a few minutes. Moreover, the Earth itself rotates, so a lot of calculations, skills and precise targeting are required."

You're a private company. Any entity or country purchasing services from you — or your competitors — needs to consider that the information gathered will be accessible to you.

"That's true, but as a private company, ISI fully owns its satellites. As such, we can sell our clients direct access to the satellites without them having to 'go through us'. The system we sell also includes a ground component, which determines what the satellite will collect and through which the satellite is controlled. The client can control the satellite's camera themselves when it's over a specific area. This is similar to how the American company Maxar operates with the U.S. government."

Shterman and his team are currently busy developing a new series of satellites, KNIGHT – advanced sensing satellites with even more enhanced capabilities. These include the ability to photograph at a resolution of 50 cm per pixel, color video, as well as short-wave infrared capabilities that dramatically improve image quality in low light conditions, fog, and smoke, revealing camouflage networks.

But CEO Segal is already looking further ahead. "The Chile project is a good example of the direction we're all heading in. The entry threshold to the space world is decreasing. We're in a transitional period between dedicated satellite computers, which cost $5 million each, to multi-core smartphone processors costing a few dozen dollars that can replace them and also execute tasks on-demand."