One could have opened this piece with the words “BB is dead.” But given their contemporary connotations, a clarification is needed: these are the initials of one of the great sex symbols of European cinema. “Sex symbol” itself is a term now often associated with a sexist discourse that judged film stars in bodily terms. Brigitte Bardot, who died Sunday at age 91, left this world perhaps somewhat forgotten, a curiosity, a former star who secluded herself in the French resort town of Saint-Tropez with her fourth husband, far-right activist Bernard d’Ormale. She resurfaced from time to time in headlines for her campaign for animal rights, as well as for a series of controversial remarks in recent decades against immigrants and Islam that led to six fines.

Former French President Charles de Gaulle once called her “as important a French export as Renault cars.” Bardot was the face of modernist French cinema and of the French New Wave, alongside actresses such as Jeanne Moreau. But she was there even before the New Wave broke out. She was a face, but also a body. It is perhaps no coincidence that Jean-Luc Godard’s film starring Bardot, “Contempt” (1963), was released in Israel under the title “The Body and the Heart.”

She projected sexuality, youth, physicality and freedom. She was synonymous with all of these, at least in the 1950s and 1960s, until her retirement from cinema in the 1970s. She embodied modernist European cinema that challenged American conservatism. She was perhaps not as naïve as Marilyn Monroe’s screen persona, nor did she project the earthy popular appeal of Sophia Loren, but she became the image of a modern male fantasy. Simone de Beauvoir defined it in a famous 1959 essay about Bardot as the “Lolita syndrome.” Indeed, the initials of her name in French are pronounced “bébé,” meaning baby.

Bardot also dyed her brown hair blond for her role in the landmark film by her first husband, director Roger Vadim, “And God Created Woman” (1956), sparking a global trend known as “Bardot blonde,” much like another blond icon, Monroe.

Although she had appeared in small roles earlier, including in René Clair’s “Les Grandes Manœuvres” (1955), her major breakthrough came with Vadim’s film, which became a global sensation. In it, Bardot played a young, liberated orphan who carries on relationships with young men, including one played by Jean-Louis Trintignant, who becomes her lover behind the back of her husband, and also attracts the attention of an older man played by Curd Jürgens.

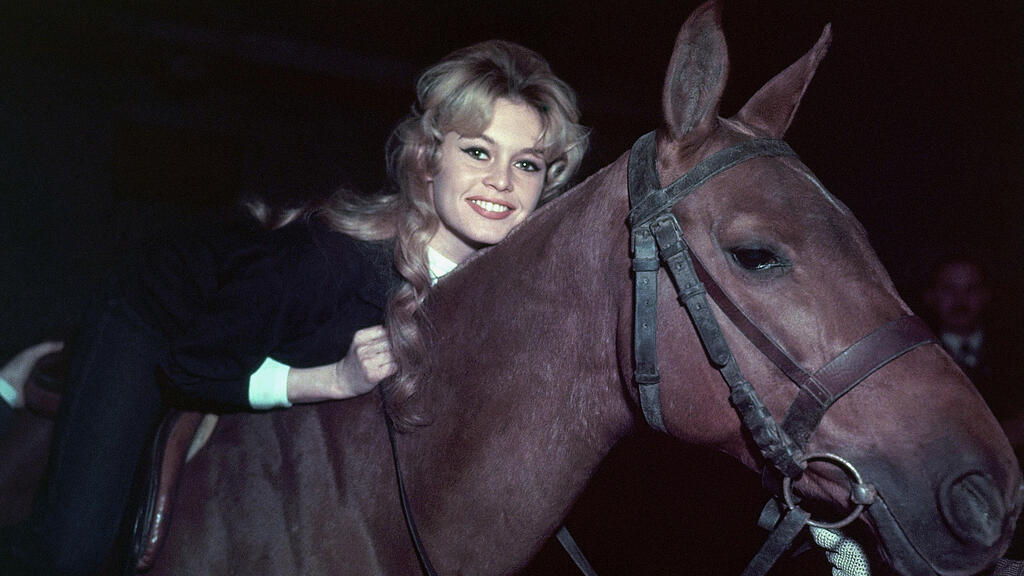

5 View gallery

Bardot was the seductive vamp, the femme fatale

(Photo: Fox Photos / Stringer, Getty)

She was the seductive vamp, the femme fatale, an embodiment of the objectification of the female body through the male gaze. Vadim was the male director, the “God” of the title, who created Bardot on screen and controlled her personally and professionally. It was scandalous, youthful, defiant cinema that was not formally part of the French New Wave, which emerged three years later in 1959, but clearly foreshadowed it.

A decade later, after the couple divorced, Vadim tried to recreate the formula with another blond who became his wife, Jane Fonda, in the futuristic camp film “Barbarella” (1968). Bardot, meanwhile, began working with what might be called more serious directors. She starred in several films by Louis Malle, including “A Very Private Affair” (1962), in which she essentially played herself, a movie star struggling with public exposure, and “Viva Maria!” (1965), a comic Western in which she appeared alongside Jeanne Moreau as a revolutionary in South America.

She also starred in Godard’s “Contempt,” playing the wife of a frustrated screenwriter portrayed by Michel Piccoli, who is hired to adapt Homer’s “Odyssey.” The film, based on a novel by Alberto Moravia, was initially intended to star Marcello Mastroianni and Sophia Loren, but Godard objected. Bardot was cast largely because producer Carlo Ponti, Loren’s husband, believed her presence would boost the film’s commercial appeal, for reasons not necessarily related to her acting. Bardot also starred in Henri-Georges Clouzot’s “The Truth” (1960), playing a woman on trial for murdering her musician lover and, like Bardot herself, challenging the values of a moralistic society.

Her activism for animal rights began after she came to the aid of Charlie, a German shepherd belonging to Alain Delon, at a ski site after the dog bit another skier. That skier turned out to be France’s finance minister at the time and a future president, Valéry Giscard d’Estaing. At her home near Paris, Bardot raised six goats, a dozen cats, a rabbit, 20 geese, a donkey and sheep.

From her marriage to French actor Jacques Charrier, who died about three months ago, Bardot had one child, Nicolas-Jacques. Bardot did not like motherhood. During her pregnancy, she declared, “I am not a mother and do not want to be.” She said she hit her stomach several times and asked her doctor to arrange an abortion. She also said the fetus was like “a cancerous growth” and that she would have preferred to give birth to a puppy.

This was not the only episode pointing to her mental distress. She attempted suicide several times, after her breakup with Trintignant in 1958 and again on her 49th birthday in 1983.

Bardot was also a fashion icon. She helped popularize the bikini following her appearance in the 1952 film “Manina, the Girl in the Bikini,” and the voluminous beehive hairstyle. She also inspired what became known as the “Bardot pose,” sitting with legs crossed in front and arms folded across the chest. Bardot recorded several songs, most notably in collaboration with Serge Gainsbourg, who wrote hits for her such as “Bonnie and Clyde” and “Je t’aime… moi non plus.” She also wrote five books. In 1973, she appeared in her final two films, “If Don Juan Were a Woman,” directed by Vadim, and “The Edifying and Joyous Story of Colinot,” directed by Nina Companeez.

Like Greta Garbo before her, Bardot became an enigma after her retirement. Every public appearance sparked media curiosity, such as her 2007 visit to President Nicolas Sarkozy while using crutches. Unlike Garbo, however, she remained active, particularly in animal rights, founding the Brigitte Bardot Foundation and selling her jewelry to support it, while also continuing to make controversial public statements. To say that Bardot’s death marks the passing of a legend, like Garbo’s, would not be an exaggeration.