During the 1970s and 1980s, a string of gruesome murders terrorized the province of Florence. The killer preyed on couples who were making love in secluded areas at night, often inside their cars. After shooting them, he removed the woman’s body, stripped her, and mutilated her, particularly her breasts and genitals, using a diver’s knife. The brutality earned him the nickname The Monster of Florence.

Between 1968 and 1985, eight double homicides were recorded, all committed with the same 0.22-caliber Beretta pistol. The killings sparked nationwide panic. Young couples no longer dared to venture into fields, forests, or even side streets, and the case became Italy’s version of Jack the Ripper, an unsolved mystery that blended sex, violence, and fear.

From The Monster of Florence

(Video: Netflix)

Over the years, several suspects were arrested and even convicted, but doubts persisted. In 2001, police suggested the murders were part of a satanic ritual in which victims’ body parts were used in ceremonies. Critics accused investigators of incompetence and sensationalism, and many Italians still believe the real killer, or killers, were never caught.

Fear, obsession and conspiracy

Theories about the case abound, from satanic cults and organ trafficking to sexual repression and police cover-ups. In one of the most shocking incidents, two German students, Wilhelm Friedrich Horst Meyer and Jens Uwe Rüsch, were killed in 1983 while traveling in a Volkswagen van. Because Rüsch had long blond hair and a slender build, police believed the killer mistook him for a woman. Pornographic material found nearby led investigators to speculate that the pair were lovers, a discovery that may have enraged the killer.

At the request of Italian authorities, the FBI’s Behavioral Science Unit created a profile describing a sexually impotent man in his 40s who lived alone or with an elderly relative and harbored a deep hatred toward women. He likely wore the same clothing and used the same weapon for each murder. The FBI even speculated that he might have consumed parts of his victims’ bodies as a means of control. The profile was never officially adopted, since none of the suspects fit it.

A popular theory holds that the crimes were committed by a group of men from Sardinia. The final murders occurred in 1985, when a mushroom picker discovered the bodies of two French tourists, Jean-Michel Kraveichvili and Nadine Mauriot. A severed nipple from Mauriot’s body was later mailed to prosecutor Silvia Della Monica with a threatening note, prompting her to leave law enforcement.

From true crime to cultural myth

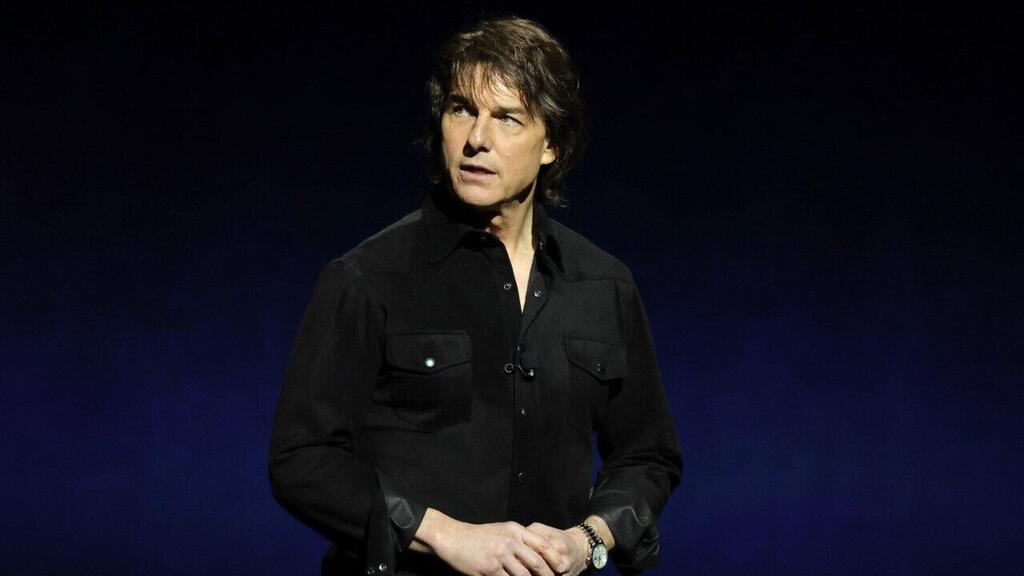

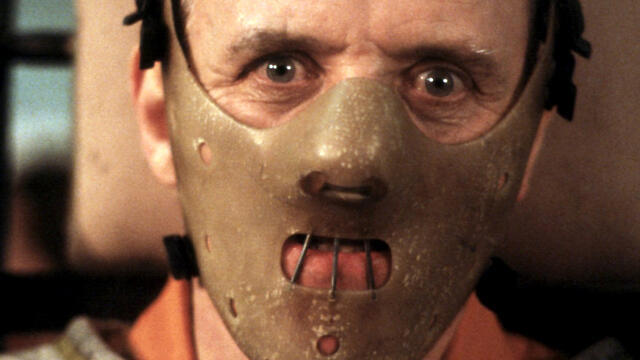

Forty years later, the Monster of Florence still grips Italy’s imagination. The case has inspired books, documentaries, and films, including Thomas Harris’s Hannibal novel and its film and TV adaptations, each referencing the Florence killings. Hollywood stars have long been drawn to the story. Tom Cruise once acquired the rights to Douglas Preston and Mario Spezi’s bestseller The Monster of Florence, before George Clooney took over the project. Despite multiple attempts, no major adaptation reached the screen until now.

Netflix’s new four-part miniseries, The Monster of Florence, directed by Stefano Sollima and Leonardo Fasoli (Gomorrah, ZeroZeroZero), revives the story for a global audience. The series premiered at the Venice Film Festival and revisits the early stages of the investigation through the eyes of the first suspect.

'The danger of turning pain into entertainment'

“The choice to tell this story means venturing into territory where evil no longer wears a mask,” Sollima told ynet. “In trying to represent it, you risk adding pain to pain or turning tragedy into spectacle. But true horror must be faced, not avoided. This series is not about solving the mystery, it is about remembering.”

Fasoli added, “We decided to tell the story from the suspects’ perspective, not the investigators’. That felt natural to us, it is the point of view of the monsters.”

Both creators emphasized their commitment to factual accuracy. “We used real names and real events,” Sollima said. “This was a true story, so we could not invent. Our only creative decision was what to leave out, to avoid confusing the audience even more.”

The choice to tell this story means entering a space where evil no longer wears a mask,” Sollima told Ynet. “In trying to represent it, you risk adding pain to pain or turning tragedy into spectacle. But true horror must be faced, not avoided. This series isn’t about solving the mystery, it’s about remembering.”

“The case is still technically open,” Fasoli noted. “For example, the family of the two French victims from 1985 continues to investigate. They are not satisfied with the court’s conclusions.”

Trauma, sexuality and repression

The creators of The Monster of Florence met with several people still connected to the case and alive today. One of them is Natalino Mele, the son of Barbara Locci, who was murdered along with her lover, construction worker Antonio Lo Bianco, on August 21, 1968, in a town near Florence. The killer shot the couple while six-year-old Natalino was asleep in the back seat. When the boy woke up, he saw his dead mother and ran to a nearby house—at least, that’s what he later claimed. The fact that Natalino was barefoot during the murder led investigators to doubt his testimony. They believed the killer had carried him on his shoulders to the nearby house.

Barbara’s husband, Stefano Mele, was eventually charged with the murder after confessing under police pressure. He later claimed he was only present at the scene. Barbara, incidentally, was one of the few victims whose genitals were not mutilated. Mele served several years in prison, but while he was incarcerated, another couple was murdered, apparently with the same gun. Barbara was known to have had affairs with several men, some of whom she brought home, and Stefano was forced to host them in their house.

Mele claimed that the real killer was a man named Salvatore Vinci, a handyman from Sardinia, a widower whose wife had allegedly committed suicide. Vinci, described as a pervert and a sadist, had lived for several years in the home of Mele and Locci and was sexually involved with both of them. Vinci’s wife provided him with an alibi. Mele was convicted based on what prosecutors said was a strong motive and on chemical tests that indicated he had fired a gun. He was sentenced to 14 years in prison under aggravated circumstances and was acquitted only in 1989.

“In that time and place,” Sollima explained, “a shepherd’s son admitting he was gay was unthinkable. The repression could easily twist a person’s psyche.”

Evil, fascination, and patriarchy

Since the Oscar-winning The Silence of the Lambs in the early 1990s, the fascination with serial killers has become an ever-growing obsession. Do you have an explanation for that?

“It is the charm of evil,” says Sollima. “There is something strangely captivating about portraying the face of evil. Maybe we want evil to feel distant from us, something abstract or exaggerated. That, for me, is what makes serial killers so fascinating—the evil itself. They represent evil, while you, as the viewer on the other side, represent good.”

Fasoli added that Italy’s culture of family and Catholicism shaped both the crimes and the response to them. “Italy has had very few serial killers,” he said. “Family ties make isolation rare. But the Monster of Florence is our biggest and most infamous.”

Sollima concluded, “This story exposes something deeply rooted in Italian society, patriarchy and the way men view women. Even today, women are killed here every day, because a man was jealous or could not bear to be left. The Monster of Florence did not just kill women; he symbolized a culture that feared female independence.”