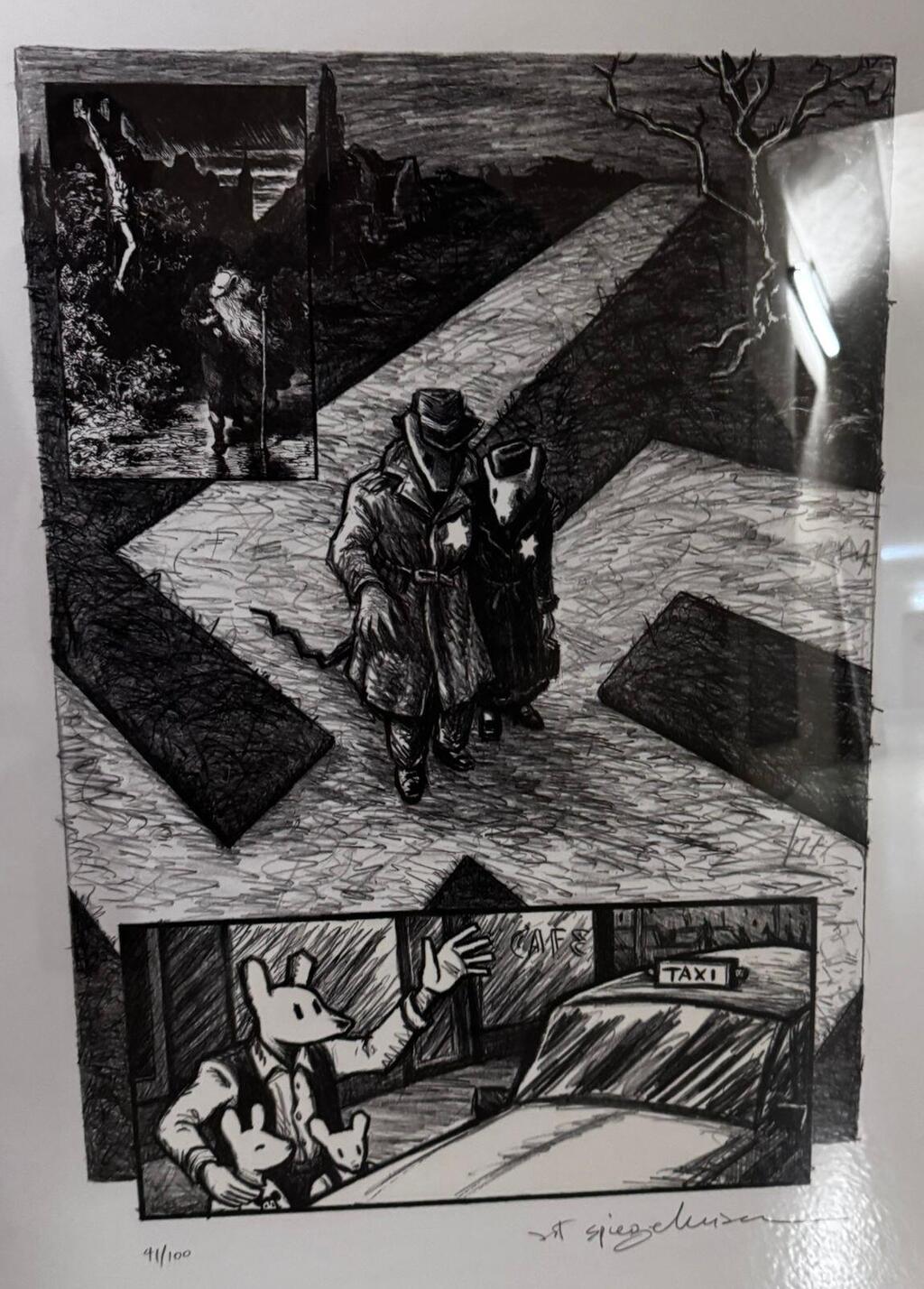

Last Thursday, a new exhibition titled Bad/Good Jews opened in Berlin. Set inside a former Nazi bunker built in 1937, the exhibit seeks to explore 21st-century Jewish identity through more than 80 works by five Jewish artists — including Pulitzer Prize winner Art Spiegelman, best known for his graphic novel Maus.

Yet this isn’t a typical gallery exhibition; it’s deliberately staged far from major Berlin art institutions, in a space saturated with the weight of history and war.

7 View gallery

The Nazi bunker where the exhibition Bad/Good Jews is displayed

(Photo: Zeev Avrahami)

Most of the works — provocative, sometimes dark and always dialogue-seeking — were created by Alexander Melamid, Michail Grobman, Marat Gelman and Yury Kharchenko, who also co-curated the exhibition. Speaking just a day before the show opened, as staff were still hammering nails into bunker walls, Kharchenko reflected on what sparked the project.

“After October 7, I felt a deep reconnection to my Jewish identity,” he said. “The traumas of the Holocaust resurfaced. Our vulnerability as Jews became stark again. We suddenly faced ideological antisemitism from both the left and right — Holocaust denial, the justification of terror and the demonization of Israel. That’s what drove Marat and me to create this exhibition. And that’s why we chose this location — a Nazi bunker that echoes the tunnels of Gaza.”

Gelman adds: “We're pushing back against how Jewish identity is being defined today — whether someone is a ‘good’ or ‘bad’ Jew, based on political affiliation. That’s why we brought together such varied works: painting, graphic art, AI-generated pieces and artists from across the political spectrum. We want to show that we’re like everyone else — good and bad, rough and refined, New York leftists and Israeli right-wingers. This is a protest movement, but it’s also a space that gives voice to the victim.”

7 View gallery

The work Genrikh Yagoda, from the exhibition Bad/Good Jews

(Illustration: Alexander Melamid)

Kharchenko challenges the notion of the eternal Jewish victim. “Even in my own family — where many were murdered under the Nazis — some took up arms, joined the Red Army and killed Nazis. Sometimes we’re the hunted mouse, like in Spiegelman’s Maus, but sometimes we’re the cat. You can’t separate art from politics. But this isn’t a space for conflict, it’s for powerful, provocative art that invites dialogue.”

From exilic fiddler to strong sabra

One large installation facing the street signals the bunker’s hidden presence; a wartime relic now repurposed to host exhibitions, parties and celebrations of life. Inside, descending steep stairs past reinforced doors, the exhibition begins with Gelman’s AI-generated images, transformed into acrylic-on-canvas pieces, that depict a violin and a rifle.

These works epitomize the show’s core theme: the transformation of the Jewish image — from the weak, exilic fiddler to the strong sabra who refuses to turn the other cheek. Sometimes the violin leans against the rifle; sometimes the rifle rests on the violin. In the series’ climax, the Jew plays a violin that is, in fact, a weapon.

When asked which they prefer — the Jew with the violin or the one with the gun — both artists pause. Having grown up in the Soviet Union and only connecting with their Jewish roots after moving to Berlin, the question isn’t simple.

“Before October 7, I would’ve had a much clearer answer,” says Kharchenko. “But now I prefer the Jew with the gun, the Israeli who defends himself. The one who makes me feel strong. I now understand that a Jew who can hold a rifle is a Jew who can afford to play the violin, but he cannot only play the violin. That might have worked in Polanski’s The Pianist.

“For me, all those Jewish artists in the current scene who adopted the anti-Israel ideology of the left, they’re the ‘useful Jews,’ the bad Jews.”

He continues: “October 7 hit me hard. So hard that I went back to synagogue after 15 years. I felt it physically. I couldn’t paint for weeks. And then I realized that’s exactly what Hamas wanted. For us to be paralyzed. To stop doing what we were born to do. The attack on Israel wasn’t only physical; it was psychological torture. And my way of fighting back was to recover and start painting again.”

After moving to Berlin, Kharchenko studied at Kahal Adass Yisroel, a yeshiva that was firebombed days after October 7. At one point, he was told, “Art is not a Jewish thing.” That same yeshiva is now a key supporter of the exhibition.

Despite the curators’ insistence that the content of the exhibition isn’t meant to be loud, the fact that Jewish artists are exhibiting in a Nazi bunker is a strong enough statement; the works themselves are visceral cries. They confront antisemitism that many thought was long buried, an art world that has turned its back on them and a deep personal fear about their future as Jews, especially in a moment when many in the Diaspora are beginning to question whether Israel is still the safe haven they believed it to be.

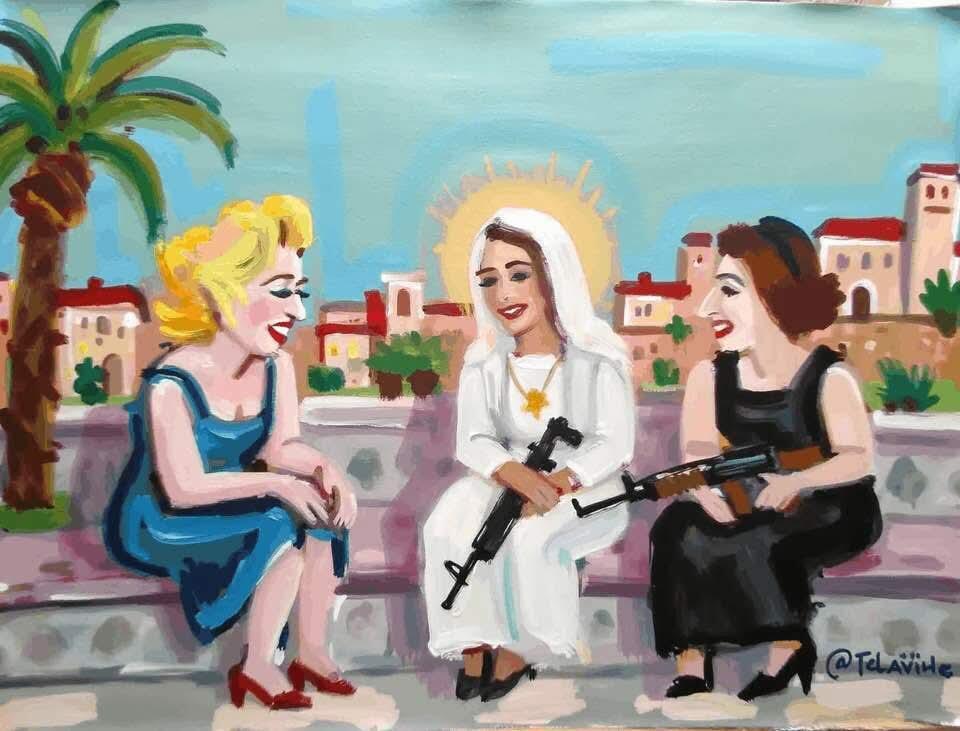

In the central room of the Bad/Good Jews exhibition, behind a wall featuring a striking painting by Gelman, depicting three Jewish women in Jerusalem, Golda Meir, Marilyn Monroe and Mary Magdalene, holding rifles (“That was my most formative image of Israel when I first visited in 1989,” Gelman says. “Women with guns!”), hangs some of the most provocative work in the show: large-scale pieces by Kharchenko.

Beside this mural is a series of paintings by Alexander Melamid depicting ten “bad Jews.” “Each responsible for at least a hundred deaths, minimum!” Gelman asserts. But it’s Kharchenko’s pieces that dominate the space, both in size and statement.

One canvas features symbols of the Israeli military, gradually darkening in tone. Another centers on Jean Améry — a Holocaust survivor and one of the first Jewish philosophers to publicly condemn left-wing terrorist violence — framed by the flags of Britain, the U.S. and the Soviet Union (this one bearing a swastika embedded within it), alongside Israeli and Palestinian flags. At the center, in a sign mimicking Auschwitz’s infamous gate, are the words From the River to the Sea, and just beneath it, a small white bubble reading “6:29” — the exact time Hamas launched its October 7 assault on southern Israel.

“It’s a nod to Dalí’s work,” Kharchenko explains, referencing the melted-clock imagery and symbolic layering. “The symbols tie Auschwitz to October 7 — a historical arc where Jews are always the victims.”

The centerpiece is part of a series of works revolving around that Auschwitz-style gate. One piece features Theodor Herzl alongside Beavis and Butt-Head protesting for Palestine; another shows a naked Snow White beneath a banner reading Arbeit Macht Frei (work will set you free), the infamous inscription on Auschwitz's main entrance gate. “People told me you can’t show pornography in this context,” Kharchenko says. “But it’s always been like this. It was like this then, and it’s like this now. Someone was listening to Beethoven a hundred meters away from where babies were being executed. And today, Holocaust memorials feel like amusement parks, complete with ice cream stands and souvenir shops.”

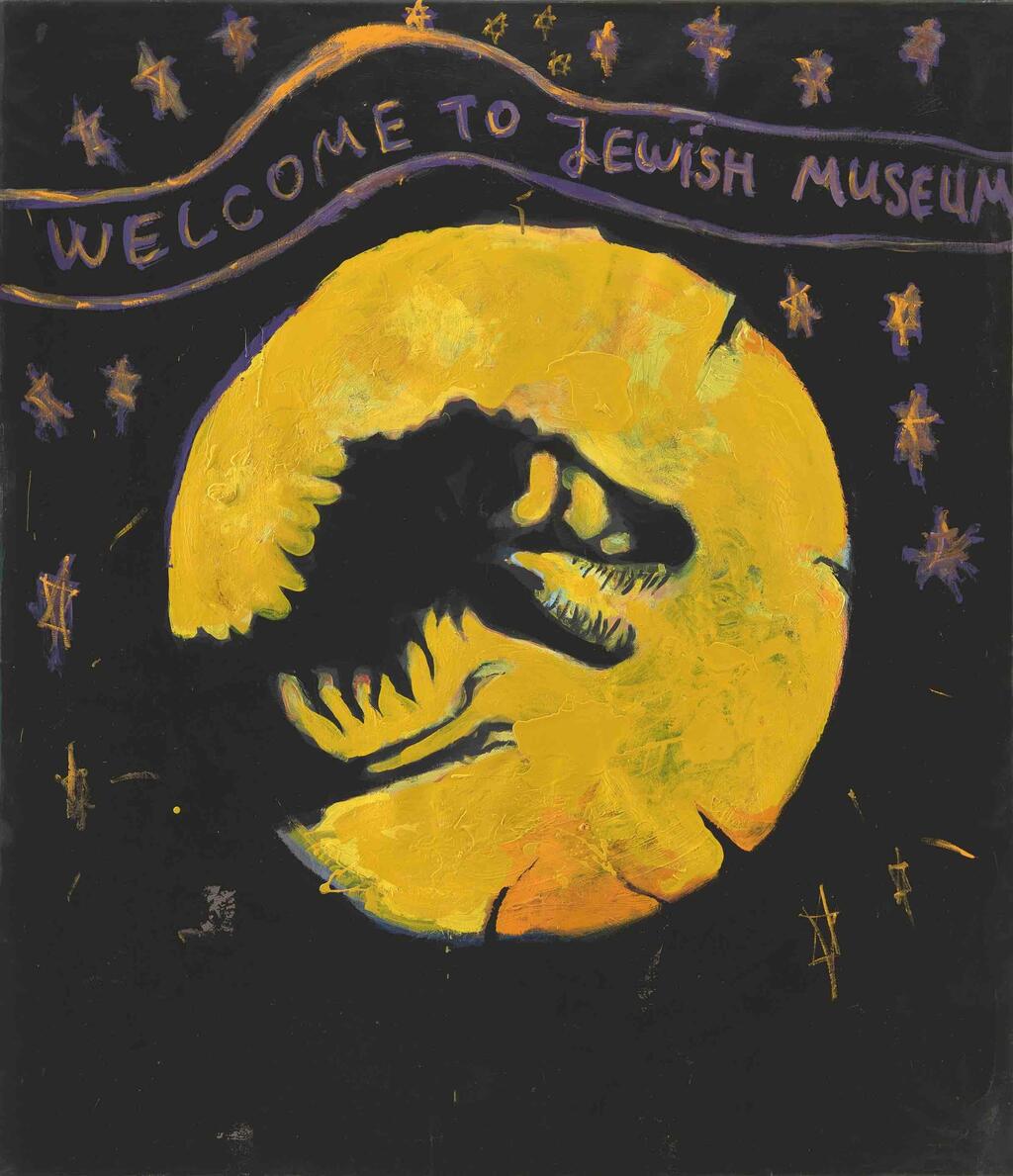

In another especially stark and surreal piece, a giant dinosaur looms over falling Stars of David — representing Jews — beneath a reimagined Auschwitz-style sign: Welcome to the Jewish Museum.

7 View gallery

The work WELCOME TO JEWISH MUSEUM, from the exhibition Bad/Good Jews

(Illustration: Yury Kharchenko)

“It touches on how we remember the Holocaust,” Kharchenko explains. “There’s Shoah by Claude Lanzmann, and there’s Jurassic Park by Steven Spielberg, who also directed Schindler’s List. Each has its place, its own way of remembering. Some prefer the raw interviews of Lanzmann, others the Hollywood blockbuster. There’s no one correct way.”

Why dinosaurs?

“At first, I thought it was more symbolic — how some Germans see Jews: as Holocaust survivors and nothing more, like dinosaurs whose whole identity is surviving extinction. But now I think it reflects a deeper fear — that we, too, as Jews, might be facing extinction.”