In October 2024, a year after the October 7 massacre, 1,000 writers and workers in the literary world, including Nobel Prize winner Annie Ernaux (Happening), Sally Rooney (Normal People), Arundhati Roy (The God of Small Things) and philosopher Judith Butler, signed a letter declaring a boycott of Israeli publishers as a protest against the war in Gaza.

They said they would not allow their books to be translated into Hebrew or published in Israel. The signatories also announced a boycott of Israeli cultural institutions that, in their words, remain silent in the face of the oppression of the Palestinian people and the “genocide in Gaza.” In fact, some of the signatories, including Ernaux, had called for a boycott of Israel even before October 7 and had already refused to allow their works to be translated.

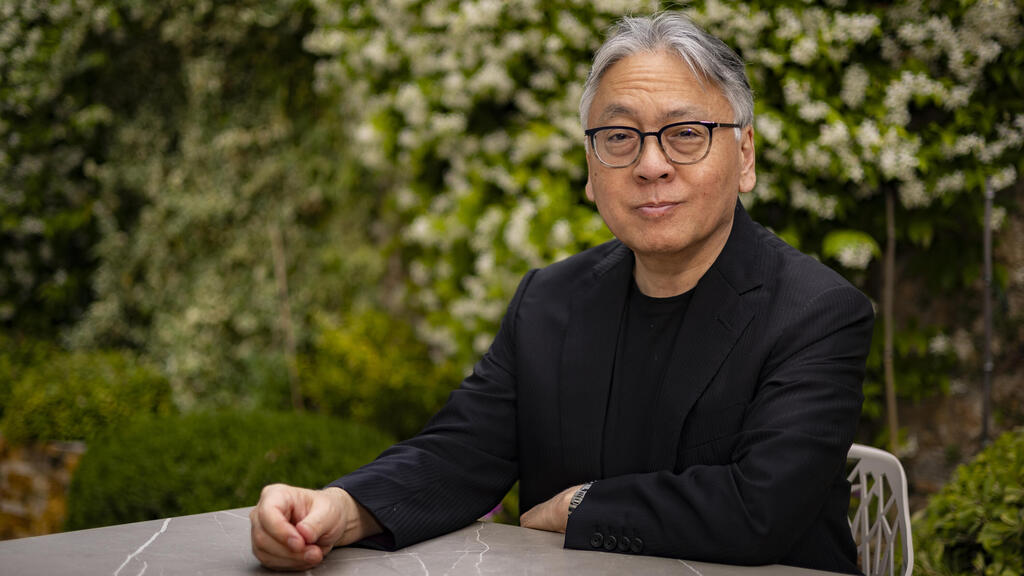

By contrast, Sir Kazuo Ishiguro, 71, the British novelist and screenwriter of Japanese origin and a Nobel laureate for books such as A Pale View of Hills, The Unconsoled, When We Were Orphans and The Remains of the Day, does not believe in boycotts. He prefers dialogue. He also has no intention of preventing his books from being translated into Hebrew.

When we met at the most recent Cannes Film Festival, Ishiguro was curious about how Israeli creative work is functioning and coping during the war. “You know, I just had lunch with Kei Ishikawa, the director and screenwriter of the film A Pale View of Hills, and we were talking about the state of cinema in Israel,” he said. “Tell me, are you still making films while the fighting is going on?”

I explained that already in the early days of the war, filmmakers were heading into the field with cameras. “Of course, documentaries are being made, but are you also making narrative films?” Ishiguro continued to ask. I told him that a filmmaker like Nadav Lapid came to Israel after October 7 to direct his film Yes, which is also competing at Cannes. I also explained the difficulties facing Israeli cinema in light of boycotts and exclusions, as well as the fact that there are now fewer budgets.

As someone born in Nagasaki, nine years after the American military dropped the atomic bomb on his hometown, killing 74,800 people in a single day and causing severe deformities among many of the survivors, it is hardly surprising that Ishiguro is drawn to questions of memory and forgetting, revenge and forgiveness, and also to how Israel is dealing with the trauma of October 7.

“How do you recover from major traumatic experiences? There is no simple answer to that question,” Ishiguro says. “The question of memory is always a difficult one, whether on the personal level or the national level. It is a very important question, for example, in Israel. And everywhere else, for that matter. Are there times when it is no longer healthy to remember what has passed? Does it harm your ability to move forward and act? Memory can preserve cycles of hatred, anger and revenge.”

In the view of the acclaimed and decorated author, memory also plays an important role in recovery. “When is it better simply to forget certain things and when is it better to remember them? Sometimes, when you experience things that are so difficult, it is better to forget. That is true on the individual level and sometimes also on the level of the state. If you spend too much time thinking about the past, it paralyzes you. It can destroy a nation’s future, split society into factions and lead to civil war.

“For me, postwar Japan is an example of a very successful recovery, not only on the level of economic reconstruction. Japan became a strong liberal democracy and remains one of the world’s most stable free and liberal democracies. It is a very interesting example of a country that moved from several decades of fascism and violence to a prosperous, peace-seeking state. To some extent, this was an achievement of deliberate forgetting, which helped healing and prevented the population from sinking too deeply into the bitterness of guilt. It gave that generation of Japanese people hope and the courage to move on. But of course, the pain and trauma are surely there somewhere.”

‘Nagasaki was the spark that ignited my writing career’

In 1960, when Ishiguro was five, he immigrated with his parents and two sisters to Guildford, England. His father began working as a researcher at the British National Institute of Oceanography, specializing in his field. He intended to stay in England for a year or two and then return to Nagasaki, but in the end, the family remained. At 19, Ishiguro set out on a hitchhiking journey across the United States, inspired by writers he admired. A year later, he returned to England, and in 1974, began studying at the University of Kent. He later completed a master’s degree in creative writing at the University of East Anglia.

After a series of short stories, he published A Pale View of Hills in 1982, his first novel. At the center of the plot is Etsuko, who emigrated from Japan and now lives alone in a country house in England. During a visit from her daughter, Etsuko recalls a summer in postwar Nagasaki. That summer, she became acquainted with a strange new neighbor, whom people regarded with suspicion. The neighbor, who has a young daughter who is also considered strange, plans to emigrate to America with her American boyfriend.

“The book A Pale View of Hills is about people trying to understand how you recover from something like the atomic bombing, searching for hope and courage,” Ishiguro says. “In such a situation, it actually takes courage just to hope. The story of the young women I described in the book, who despite everything they went through are still willing to take another risk in order to improve their lives, is very moving to me. That courage is also passed on to the next generation, to Etsuko’s daughter, who wonders whether to bring a child into the world and is afraid. Over the course of the book, she finds the courage to take a step forward. In general, earlier in my career, I was always interested in people who struggled with their past and their memories.”

A Pale View of Hills marked the beginning of a remarkable career, and in 2025 it was also adapted into a film, which competed, among other sections, in Un Certain Regard, the Cannes Film Festival’s second-most prestigious framework, and is now being released in Israeli theaters.

How did being born in Nagasaki shape your life and your work?

“The central role Nagasaki played for me is that it was the spark that ignited my writing career. Until I began thinking about Nagasaki, I dreamed of being a singer and songwriter, with no connection to Japan. I wanted to be like Leonard Cohen, Bob Dylan and the like, and I wrote songs.”

Record companies were not enthusiastic about the songs. “At that point, I began writing short stories set in Nagasaki, and those were actually published. My mother said to me: ‘If you’re going to be a writer, it would be right for me to pass on some of my memories of World War II to you.’ They weren’t necessarily horrific memories. Without my mother’s initial push, I’m not sure I would be writing narrative novels today. I had ambitions to write other kinds of books, and when I sat down to write A Pale View of Hills, I decided I would not make direct use of any of her stories, so nothing she shared with me appears in it or in the film. The main character is not my mother. That was a clear decision I made.”

You were five when you left Nagasaki and returned at 35. Do you actually remember your childhood there?

“Yes, of course, though not memories from the period described in A Pale View of Hills. I remember hikes we took in the mountains around the city. On one of those trips, I rode a cable car for the first time, and that scene made its way into the book. There’s also a boy in the novel who wins a prize at a shooting gallery at a fair, and I, too, won a similar prize as a child. I didn’t shoot a pistol — it was more like a rifle — but I won a large crate of vegetables. Through writing, I kept Japan alive in my mind. A Japan that no longer exists. Since Mr. Ishikawa brought back real memories I had put into the novel in the film A Pale View of Hills, the premiere at Cannes was an interesting experience for me.”

Ishiguro’s relationship with cinema began in childhood. Watching the film Ikiru, by Japanese director Akira Kurosawa — about an aging bureaucrat who learns he is terminally ill and decides to search for meaning by working to establish a children’s playground in a poor Tokyo neighborhood — shaped the way he sees the world and his writing. Years later, he wrote the screenplay for the film Living, starring Bill Nighy, which was based on Ikiru and earned an Oscar nomination. Ishiguro is also a great admirer of Steven Spielberg.

“I also work on the side as a screenwriter, and I’ve served on juries at Cannes and Venice. Cinema is a huge part of my life. I think many writers of my generation feel the same way. It takes quite a long time to read a book, but you can get through most of a director’s filmography in four days,” he says, bursting into laughter. “Even less, if you’re willing to enslave yourself.”

Several of Ishiguro’s books have been adapted for the screen, the most famous being The Remains of the Day, which won the Booker Prize in 1989. The film, directed by James Ivory in 1993 and starring Anthony Hopkins and Emma Thompson, was nominated for eight Academy Awards. The success made Ishiguro famous worldwide. The story centers on Mr. Stevens, a British butler devoted to his work and meticulous in its execution, at the expense of his personal life. After the death of Lord Darlington, who sympathized with fascism and Nazism, the estate falls into decline.

“Like one of the characters in A Pale View of Hills, the butler is an older man who looks back on his life and realizes that the values upheld by the society he lived in have changed so dramatically. Everything he once took pride in, and on which his life was built, suddenly becomes a source of endless shame. Or at the very least, wasted effort, despite the fact that he did everything he possibly could. And now the years he has left are short, and he has no second chance — and he knows it.”

Ishiguro does not believe that film directors betray his original books. “I like to think of my books as if they were Greek mythology, or some kind of legend. A story that can be passed down from generation to generation, and that in each new era and place receives a different adaptation.” He does not cling too tightly to the original text. “Sometimes it’s creative laziness. The story is already there, and it’s much easier to just run with it than to change it. At a certain point in film productions based on my books or screenplays, I step away, because my presence is very distracting. Later, of course, I pop up again.”

‘There are many opportunities in artificial intelligence, but also enormous dangers’

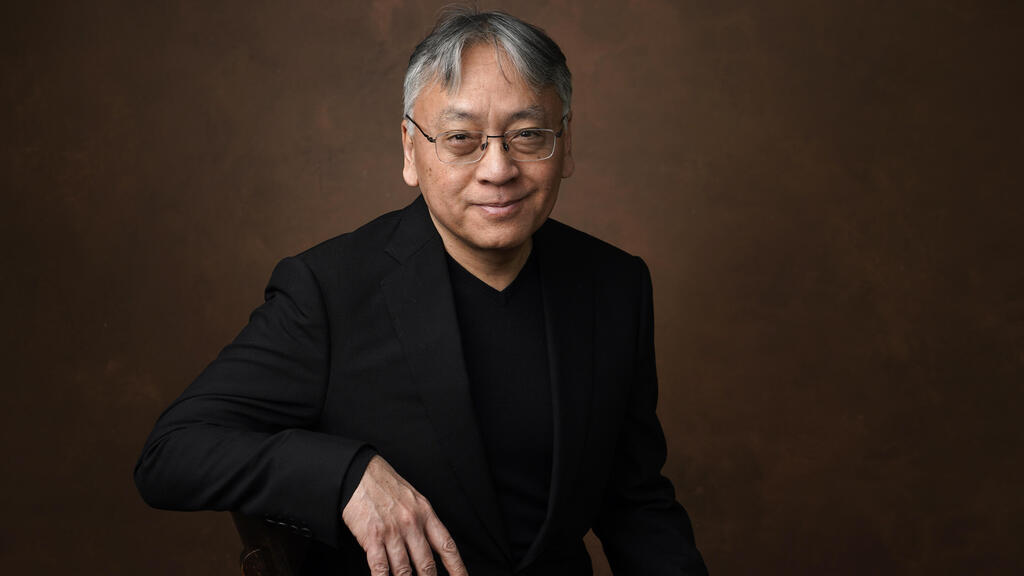

In 2017, as noted, Ishiguro — whose books move across genres — won the Nobel Prize in Literature. When he received the news, the first thing he did was call his mother, who was then 91. He mentioned her and Nagasaki in his acceptance speech. In the past, Ishiguro had declined and refused several prizes. This time, he could not refuse.

“I can say with complete honesty that the Nobel Prize is an institution I greatly respect, and I have immense respect for the previous literature laureates who have received it since 1901. Many of my greatest heroes are on that list,” Ishiguro said at the time in an interview with the Nobel Prize website. “The Nobel Prize is an award that has managed to capture the imagination of the world. Not as a marketing tool, but as something that demonstrates ideals about humanity and what we aspire to, and that is quite rare: peace, cooperation between people, humanity’s effort to improve our civilization.”

7 View gallery

Kazuo Ishiguro at the Nobel Prize ceremony in 2017

(Photo: Pascal Le Segretain/Getty Images)

The judges wrote in their citation: “In novels of great emotional force, Ishiguro has uncovered the abyss beneath our illusory sense of connection with the world. Memory, time and a lifelong sense of self-deception are central themes in his work. His language is marked by restraint, even when describing dramatic events.”

In A Pale View of Hills, some of the characters grapple with questions of alienation and belonging, common among those born in one place and living in another. Were these issues you yourself faced as a child immigrant?

“It was less acute for me, because I was very young when we emigrated from Japan. I started first grade with my British peers. For my sister, who is four years older than me, it was certainly much harder. At the time, my family was quite isolated. There were no other Japanese people around us. But I didn’t experience an identity crisis. Today, for example, London is multicultural. Many people feel they must belong to a particular minority group, and resistance quickly emerges against attempts to distance oneself from that group in favor of other forms of belonging.”

On this subject, Ishiguro draws insights from the 33 years he has lived with his family — he is married to Linda, a social worker he met through a charity project for the homeless, and they have one daughter, Naomi, herself a writer — in the Golders Green neighborhood of London. “It’s a Jewish area, and one of the big issues in the neighborhood isn’t fear of antisemitism, but rather the question of whether young people should marry outside the community and assimilate, or stay strictly within it. Among many people we know in the neighborhood, this conflict is very much alive. Some say, ‘Young people should leave and marry whomever they love,’ while others say, ‘Well, when they’re children, just introduce them to other Jewish children so that eventually they’ll marry Jews.’”

Are you talking about the ultra-Orthodox community in Golders Green?

“In our area there are Jews from across the spectrum, but of course there are also very devout Jews, and the fiercest debates take place between different groups within the community. A Pale View of Hills also raises the question of how you build a life in a society that is completely different from what you know, and the risks and hopes that come with that. The book speaks to the urge to seek a better life by crossing into an ‘other world.’”

These days, Ishiguro is developing a new screenplay and also working on a new book, which he describes as “silly.” When I ask why, he replies, “It’s a comic thriller.” In the past, he has written a detective thriller as well — When We Were Orphans, about a celebrated detective who returns to Shanghai, the city of his childhood, in 1937 to investigate a family mystery.

7 View gallery

Kazuo Ishiguro (left) with the cast of A Pale View of Hills at the Cannes Film Festival

(Photo: Pascal Le Segretain/Getty Images)

In his books, Ishiguro does not write only about the past. Never Let Me Go, which won awards when it was published in 2005, was in fact a science fiction novel about children raised to become future organ donors. In Klara and the Sun, published in 2021, the narrator is Klara, a solar-powered robot trained by artificial intelligence to serve as a companion to a girl dealing with a mysterious illness. “Director Taika Waititi (Jojo Rabbit, the Thor films) is now adapting Klara and the Sun for the screen — starring Jenna Ortega, Natasha Lyonne and Amy Adams,” Ishiguro says, laughing. “Taika prefers to work entirely on his own. Even his producers don’t know what he’s doing, and it makes them anxious. They’re very worried. But in the end, you have to respect the fact that everyone works differently.”

You’ve written about the future and technology. What is your relationship with the current AI mania?

“I don’t use ChatGPT, and I don’t even touch social media. Artificial intelligence fascinates me, and I was ahead of my time on this subject. I even participated in conferences on AI long before people began talking about it. I became friends with computer scientist Demis Hassabis, one of today’s AI geniuses and a co-founder of DeepMind, shortly after his program AlphaGo defeated the world champion Go player Lee Sedol in South Korea. That seemed like a turning point. That’s how I learned a great deal about how different the new AI is from what we were used to thinking, and about its capabilities. That was also what lay behind the idea for Klara and the Sun.

“Today I’m less up to date and don’t use the commercial versions of AI that have come onto the market, but I haven’t changed my view of the great danger inherent in this technology, or of the great excitement and benefits it offers. The same things worry me, and the same things excite me. There are many opportunities in artificial intelligence, but also enormous dangers.”