Quietly and out of the spotlight, Israel’s Water Authority is preparing for a historic moment: for the first time anywhere in the world, desalinated seawater will soon be pumped into a freshwater lake. The Sea of Galilee, Israel’s national reservoir, will be the global pioneer in this groundbreaking project.

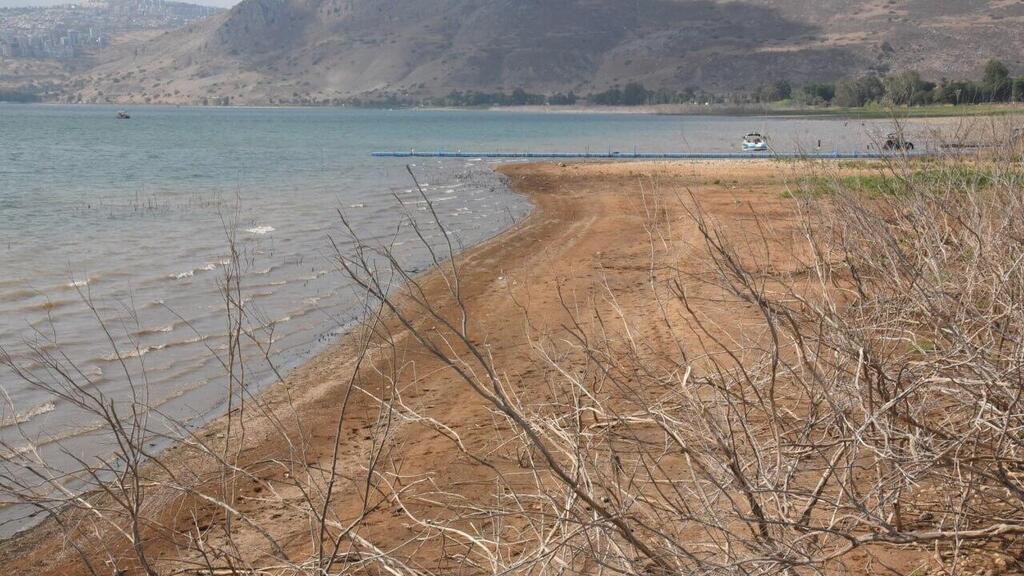

After a series of droughts pushed the lake dangerously close to the “black line” — the point where water extraction is considered harmful — officials are now moving to reverse years of decline. On Monday, the lake’s water level stood only 22 centimeters above the lower red line. For years, Israelis and the millions of vacationers at the Sea of Galilee have witnessed the lake recede, sometimes walking hundreds of meters to reach the shoreline. Public campaigns such as “Israel is drying up” became part of national life.

Now, the Water Authority is set to take unprecedented action. In the coming weeks, desalinated water from Israel’s Mediterranean coast will be diverted into the Sea of Galilee. “The lake is losing a centimeter of water a day in these dry summer months due to natural evaporation. We are eagerly awaiting the inflow and hope that with desalinated water we can guarantee a high lake level for Israelis and tourists alike,” said Idan Greenbaum, chairman of the Kinneret Cities Association.

Firas Talhami, head of the Water Authority’s northern region, recalled how the idea first emerged after the severe drought of 2013–2018. “We dropped below the lower red line and came close to the black line. That’s when experts proposed reversing the National Water Carrier and channeling desalinated water into the lake. Ultimately, this became the chosen solution,” he explained.

Although several rainy years delayed the project, planning and construction continued. Hundreds of millions of shekels were invested in laying new pipelines from the Eshkol site to the Zalmon River, where the water will enter the Sea of Galilee. Pumping stations along the coast were upgraded to move water eastward, a reversal of Israel’s traditional water flow.

By late October or early November, the Water Authority expects to begin pumping up to 5,000 cubic meters of water an hour — tens of millions of cubic meters over the autumn and winter months — to stabilize the lake. “This is a historic event that has never been done before anywhere in the world,” Talhami said. “We also considered the ecological impact, and the project will restore the Zalmon stream into a perennial waterway, reviving plant and animal life.”

The desalinated water will travel between 100 and 150 kilometers, drawn from plants in Ashdod, Hadera, and other coastal sites. Yossi Yaakobi, deputy CEO for engineering and innovation at Mekorot, Israel’s national water company, noted that the long-term plan is to increase capacity to 15,000 cubic meters per hour as more desalination plants come online. Israel has invested about 1 billion shekels in the “reverse carrier” project, which included reinforcing pumping stations, building large reservoirs, and upgrading water infrastructure nationwide.

If successful, the Sea of Galilee project could become a model for water management in a warming world where droughts are increasingly common.