Brain metastases are among the deadliest and most frustrating complications of breast cancer. In many cases, it is not the primary tumor that determines a patient's fate, but the cancer cells’ ability to penetrate vital organs, adapt to foreign environments and thrive. Despite major advances in biological and immunotherapy treatments in recent years, the brain remains a therapeutic challenge with limited options and a poor prognosis.

A new study led by researchers at Tel Aviv University’s Faculty of Medicine offers a biological explanation to a long-standing question in oncology: how breast cancer cells succeed in “settling” in the brain, and why this occurs only in some patients. The findings could lead to new drugs and enable personalized medical monitoring, including early detection of patients at high risk for brain metastases and targeted intervention in early stages of the disease.

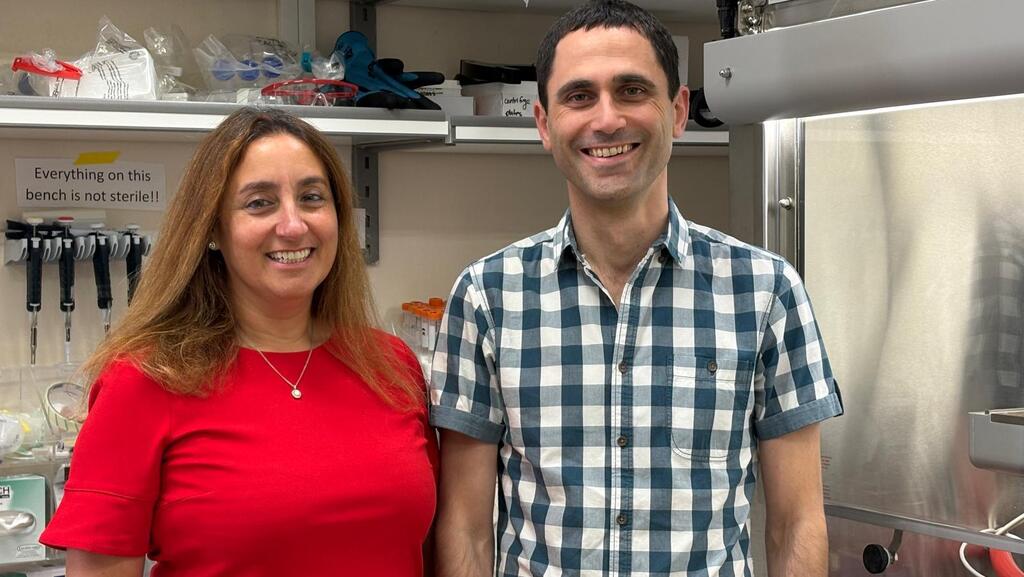

The study, published Monday in Nature Genetics, was led by Professors Uri Ben-David and Ronit Satchi-Fainaro, with Dr. Kathrin Laue and Dr. Sabina Pozzi, all from Tel Aviv University. It involved dozens of researchers from 14 laboratories across six countries: Israel, the United States, Italy, Germany, Poland and Australia. The work combined clinical and genomic data from cancer patients, advanced laboratory experiments and mouse models to investigate one of the most elusive and lethal mechanisms of breast cancer.

Breast cancer is one of several types, including melanoma and lung cancer, with a relatively high tendency to spread to the brain. While treatments for the primary tumor have improved, brain metastases remain a turning point in the disease, with limited treatment options and poor outcomes.

“Most cancer deaths are not caused by the primary tumor, but by metastases to vital organs,” said Satchi-Fainaro, head of Tel Aviv University’s medical school and cancer research center. “Among them, brain metastases are the most lethal and difficult to treat. One of the most important unanswered questions in cancer research is why certain tumors metastasize to specific organs. Despite the importance of this phenomenon, very little is known about the factors and mechanisms behind it.”

This question is particularly relevant when it comes to the brain, which is protected by the blood-brain barrier that blocks many substances and cells from entering. “Blood vessels in the brain are very selective,” said Satchi-Fainaro. “Yet cancer cells from the breast manage to break through and survive there. The question is, how?”

Once in the brain, cancer cells face an unfamiliar environment. Unlike the fat-rich tissue of the breast, the brain consists of neurons, immune cells and astrocytes — cells that support and nourish neurons. “This is a hostile environment that cancer cells aren’t supposed to know,” she said. “But we found that astrocytes don’t just ignore the cancer cells, they actually help them settle in the brain. That’s why we were so curious to study this process, how the cells arrive, survive and cooperate with astrocytes to thrive.”

The study combined two complementary cancer research approaches at Tel Aviv University: the lab of Prof. Ronit Satchi-Fainaro, which examines how cancer cells interact with their surrounding microenvironment, and the lab of Prof. Uri Ben-David, a cancer genetics researcher who focuses on chromosomal changes in cancer cells.

Using clinical and genomic data from thousands of breast cancer patients, along with laboratory experiments, mouse models and tumor samples taken directly from surgery, the researchers set out to determine what allows breast cancer cells to spread specifically to the brain. They compared genetic features of brain metastases with metastases in other organs and with primary tumors that do or do not tend to spread to the brain.

Their analysis pointed to the gene p53, known as the “guardian of the genome” for its role in triggering cell death when damage occurs. The researchers found that p53 was already inactivated in primary breast tumors that later formed brain metastases. To test its role, they engineered otherwise identical breast cancer cells that differed only in p53 activity, using CRISPR gene editing. “When we injected the cells into mice, loss of p53 dramatically increased their ability to form brain metastases,” Satchi-Fainaro said.

Further investigation showed why p53-deficient cells thrive in the brain. The gene normally regulates fatty acid production, a metabolic process that is critical in the brain, where fats are scarce. When p53 is impaired, cancer cells increase their ability to produce fatty acids, helping them survive and grow in the brain.

The team also identified enhanced interaction between p53-deficient cancer cells and astrocytes, support cells in the brain. Astrocytes supply cancer cells with building materials, allowing them to reshape the brain environment and grow more rapidly.

These findings were confirmed in mouse models using both human and mouse breast cancer cells, as well as in brain metastases taken directly from breast cancer patients. In the human samples, the researchers observed reduced p53 activity alongside increased activity of SCD1, a gene involved in fatty acid production, and a strong association with astrocyte presence.

The findings could carry significant future therapeutic implications, the researchers said, by identifying a biological vulnerability in breast cancer brain metastases. “The mechanism we discovered is not only essential for the formation of brain metastases, it is also their weak point,” said Prof. Uri Ben-David. “If we target this mechanism, we may be able to damage brain metastases — a condition that currently has no effective treatment.”

The team tested several drugs that inhibit SCD1, a gene involved in fatty acid production. The drugs, developed originally for other diseases and now at various stages of development, proved effective against metastases with impaired p53. In mouse models and in brain metastasis samples from breast cancer patients, blocking SCD1 significantly reduced metastatic growth. “In mice that received the treatment, tumor progression was markedly slowed and survival rates increased,” said Prof. Satchi-Fainaro. “This shows there is real potential here.”

Beyond future therapies, the researchers said the findings may have immediate clinical relevance. The p53 mutation identified in the study could serve as a biomarker to identify breast cancer patients at higher risk of developing brain metastases early in the disease. “If a patient carries this genetic alteration, her risk of brain metastases is higher,” Ben-David said. “That could justify closer monitoring, including brain MRI scans, which are not part of routine follow-up for breast cancer patients today.”

The findings could also inform treatment decisions. While oncologists have many biologic drugs available, only some can cross the blood-brain barrier, and those that do often cause more severe side effects. Identifying patients at higher risk for brain metastases could help guide choices between more aggressive treatments and more tolerable options. “The clinical relevance is not only in developing new drugs,” Ben-David said. “It may also affect how breast cancer patients are monitored and treated today, using tools that already exist.”

The project was supported by competitive grants from the Israel Science Foundation, the Israel Cancer Research Fund and Spain’s Fundación La Caixa. It was also part of broader research supported by the European Research Council, including an Advanced Grant and Proof of Concept grant in Satchi-Fainaro’s lab and a Starting Grant in Ben-David’s lab.