When the brain wanders, when our thoughts drift and roam, this is not a failure. Rather, mind-wandering plays a necessary role in our daily lives, argues Prof. Moshe Bar, a brain and creativity researcher at Bar-Ilan University, challenging one of the most deeply rooted beliefs of our time: that focus is a virtue and wandering thoughts are a problem.

Later in the conversation, he also challenges other assumptions we have grown used to, such as the idea that we use only 10 percent of our brain, or that attention deficit disorder is truly a disorder. It isn’t, he says, because we do not always need to be focused. He insists that mind-wandering is so beneficial that nature would not invest time in it otherwise.

“It’s not that I’m against focus and concentration,” Bar emphasizes. “I’m simply saying there’s a time for focus and a time for wandering.” Indeed, in his thought-provoking book Mindwandering, published in 12 languages and now appearing in Hebrew (Techelet Publishing and Bar-Ilan University), he presents brain research showing that the very moments when we are “not focused” provide the foundation for creativity, emotional understanding and decision-making. And so, in an era that sanctifies productivity, concentration and self-control, a convention-breaking professor offers an almost subversive idea: less discipline and structured thinking, less fighting the brain’s impulses, and more listening to its need to lose focus in favor of staring into space and drifting along associative paths.

A vital function

“Studies have found that our brain wanders 49 percent of the time. That is, for half of our waking hours, our consciousness is not where our body is,” he says. “We all know the experience of sitting in a university lecture while our body is there, but our mind is off on a jeep trip in the Sahara. And since wandering exists and accompanies us 50 percent of the time, meaning nature has invested so much energy in it, it’s a sign that it serves vital functions.”

What functions, for example?

“One of the main functions is forward planning. For instance, you’re going to a job interview, meeting friends for dinner or negotiating with someone. You don’t arrive at those situations as a blank slate saying, ‘Let’s see what happens,’ but after your brain has run simulations and possible scenarios of what might occur in each specific situation. We rehearse these again and again, and we arrive as prepared as possible even for situations that may never actually happen.”

What do you mean by situations that may never happen?

“For example, I might think during our meeting about what would happen if there were a power outage here, or wonder whether my car has been stolen. In other words, we prepare even for situations that are highly unlikely to occur, because we always want to be ready.”

And does it have to be something negative?

“No. I can also imagine myself lying in a hammock in Jamaica, drinking coconut juice. That’s never happened. But I can let my thoughts wander into a situation that never took place. That situation enters my memory bank, and I can use it just like things that actually happened. Our memory is a repository of our experience and our experiences. Contrary to what people think, it’s not just an archive of the past, it’s primarily meant to serve our future.”

So wandering thoughts can create a situation we never experienced and store it in memory as if it happened? Is that what’s called thoughts creating reality?

“Yes. The book discusses how we learn from our imagination. The more you wander in your imagination and manage to create a richer, more sophisticated simulation, the higher your level of preparedness.”

In the context of creating imagined scenarios, Bar says the brain is not only fascinating but also disappointing in its desire to minimize uncertainty: “We like surprises in certain situations, but in the vast majority of cases we want to be prepared for what’s coming.”

That sounds like anxiety, doesn’t it?

“People with a clinical diagnosis of anxiety or depression don’t manage uncertainty very well. When someone is stuck with uncertainty for a long time, critical areas of the brain change. For example, the hippocampus, which is crucial for memory, loses volume. It’s astonishing that a way of thinking can affect the structure of the brain.”

Can you define uncertainty? After all, our entire lives are one big uncertainty.

“Uncertainty is a situation in which we cannot predict a future that is relevant to us with a satisfactory level of accuracy. I may not have the tools to predict how the stock market will behave tomorrow, and that’s fine if the stock market doesn’t concern me. But if uncertainty arises about what I’ll be asked in a job interview tomorrow, I can either generate simulations in my head and arrive more prepared and confident, or tell myself, ‘Oh no, what will they ask me? I might not know what to answer,’ and thus trap myself in repeated thoughts of uncertainty.”

So someone who doesn’t generate the simulation and calm down isn’t experiencing the kind of mind-wandering you’re describing, but remains stuck?

“Natural thought is open and associative, allowing us to predict things beyond the here and now. In contrast, among people with anxiety and depression there are too many brakes on thinking, resulting in closed, circular thinking around the troubling issue. For example, you get stuck on something negative you said to someone yesterday and can’t free yourself from it through simulation. You fall into a repetitive, ruminative pattern, walking in circles around a specific thought, usually a negative one. In anxiety, the circles revolve around negative ‘what ifs.’ In depression, around negative ‘what was.’ In both anxiety and depression, we are stuck in loops.”

The benefits of staring into space

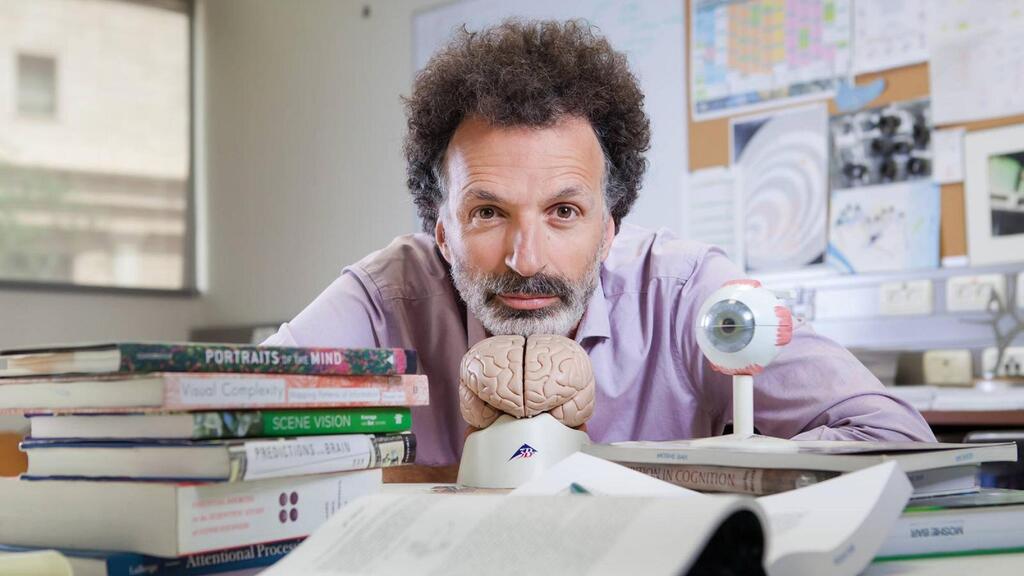

Prof. Bar, who says he is in love with his work and could not imagine waking up with a smile for any other job, brings to the table fMRI brain-imaging tests, which help researchers discover what happens in the brain when people do different things, such as identifying faces or sounds.

“This is how it was discovered that even when a subject is deliberately asked to do nothing, to rest and not think about anything, the brain is still intensely and uniformly active. And this network that operates even when we are doing nothing is called the ‘default mode network,’” he explains, noting that it is precisely there that mind-wandering occurs.

Prof. Bar, tall, smiling and good-natured, who often laughs as he talks about his research, doesn’t just speak about wandering — he practices it. His academic path reflects it as well. He began with a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering at Ben-Gurion University, completed a master’s degree in mathematics and computer science at the Weizmann Institute, and earned his doctorate in psychology and brain research in California.

“In my defense, from the outside it looks like attention deficit disorder, but everything was connected. There’s a common thread running through the fields, and it’s not as scattered as it seems,” he laughs, his blond curls laughing along with him.

He grew up in Dimona, where his mother worked with at-risk youth and his father worked at the nuclear reactor. As a teenager, he left Dimona and moved in with his grandparents in Rishon LeZion to study electronics in high school, and he served in the Air Force. Today he lives in Tel Aviv and is a devoted father of three children aged 14 to 25.

At this point, he volunteers that his thoughts are currently wandering to his boxing training later that evening, a field he took up a few months ago.

“I’m addicted. There’s a chance my next book will be about the brain and boxing, if I still have a brain left after all the blows. It’s a field that requires rapid responses based on minimal data. At the same time, I see a connection to my Talmud studies, which I’ve taken up in recent years, where in every situation you also have to imagine out loud all the possible scenarios.”

Speaking of scenarios, in the book you talk about a human brain that was not designed for continuous thinking, and about the gap between brain biology and cultural and technological demands.

“You’re asking how we close the gap? It’s like a tug of war. I’m working on an article, if I were 100 percent focused on it and didn’t think about anything else that might distract me, on the one hand I might finish it very quickly, but on the other hand it might be less creative and interesting. That’s why I argue that we need to respect this wandering. Because another important thing that happens during wandering, beyond planning, is what we call ‘creative incubation.’ In this state, the conscious and unconscious mind work on solving a problem we’ve encountered but haven’t yet solved — and the solution emerges behind the scenes of thought. The result is that kind of ‘aha’ moment.”

A moment of discovery.

“One that often comes with a subjective feeling of something mystical. ‘Where did this brilliant idea come from?’ I ask myself. But you have to understand that it’s a kind of incubation. That’s why I encouraged my children to stare into space, while some parents tell their kids, ‘Get up, do something, go play sports.’ There’s room for both approaches, we just need to allow space for the one that has gotten a bad reputation.”

Which is staring into space.

“Yes. There are certainly cases where I need to be focused and solve my problem, versus situations where I’m waiting for the incubation to finish and therefore allow myself to wander through the forest of thoughts.”

Doesn’t a culture that sanctifies focus instead of staring into space produce exhausted people?

“There are cultures that sanctify focus, and in my view it comes at the expense of creativity. Then there are more creative cultures that are less disciplined and perhaps also less productive. Without a doubt, we Israelis are a nation with attention deficit disorder.”

I call it attention inspiration.

“I’m all for it. Do you know how many emails I’ve received from people around the world who read the book and wrote, ‘Thank you for giving me permission both to stare into space and to have attention deficit disorder’? Not long ago I gave a lecture in Sri Lanka to a large cybersecurity company, where I spoke about cognitive fatigue among people who work long hours in monotonous roles in front of a computer. There are no muscles involved, so what gets tired? It turns out that when neurons operate, they also produce waste — things in the brain break down. Under normal conditions, the brain knows how to clear and recycle this waste and we’re fine. But in cases of prolonged focus, for example, people who stare too long at X-ray screening machines at airports, the brain performs the same action for too long and doesn’t have enough time to clear the neurological waste. Since it includes toxins, the result of its accumulation is a decline in our decision-making ability. And interestingly, the only solution to this accumulation is sleep.”

In the book, you draw a sharp distinction between an exploratory brain and a brain stuck in a loop of fear, offering a new understanding of anxiety, guilt and burnout. What’s the difference between productive wandering and exhausting wandering?

“I discuss this at length in the book, and it’s important to go into depth to provide tools for distinguishing between healthy and unhealthy wandering, including examples of our limited ability to control our thoughts. For instance, there’s a well-known experiment in which people were told not to think about white bears. Of course, the only thing they could think about was white bears. In that context, there are ways to improve or optimize our wandering. For example, if I’m about to go for a run or a long drive and I know my mind is going to wander, beforehand I might read a draft of an article I’m writing. That increases the chance that the topic will pop up during spontaneous mind-wandering.”

So your recommendation is to put the brain into an exploratory mode?

“It depends. If you need to finish an article or your tax report, you don’t want to explore, you want to do one plus one and reach your goal in a reasonable amount of time. You won’t get anywhere if you spend all day dreaming.”

So how do you find the golden mean?

“As in many situations in life, a large part of the solution is being aware that we have different modes of thinking, and that each of them, unless it’s pathological, like in anxiety, depression or trauma, has a purpose that fits the situation. For example, if I’m going to a soccer match or a board meeting, each requires a different state of mind. The friction happens when there’s no separation, for instance, when a hyperactive child sits through a philharmonic concert.”

The prevailing view is that mind-wandering is a problem that needs fixing. Who’s responsible for that perception?

“It’s true that I often regret the fact that children who daydream in class or think about something else are told they’re not OK and need to come back to the here and now. It stifles their creativity. On the other hand, a teacher can’t have a class of 40 daydreamers not learning the multiplication table, so I don’t want to blame the education system, it has clear goals it needs to meet. This connects to the idea that there’s a time for every mode of thought, and that in most cases nature oscillates in a self-balancing way. You dream for a few minutes, then return to the board, ask what you missed and fill in the gaps. It’s not that you disappear into wandering for an hour and a half. Nature knows how to make us oscillate between these states without the sides necessarily noticing.”

Still, what is the biggest mistake we make about how the human brain is supposed to work? What haven’t we understood?

“First of all, we haven’t understood what we’ve just been talking about, that we need to respect the wandering space. And also that the creative process requires two modes of thinking. It’s not boom, I’m creative, there are stages. We liken the brain’s process in searching for a creative solution to a diamond. There’s the first stage, which is open thinking, that’s when we shoot ideas in all directions.”

Brainstorming?

“Yes. Even brainstorming has rules. For example, there are no stupid ideas, no ‘this won’t work,’ no ‘this has already been done,’ and no boss in the room, the goal is to generate as many ideas as possible. Then comes the other side of the diamond: closure. The brain says, ‘I’ve generated 37 ideas and I need one. Let’s evaluate the effectiveness of each idea and choose the best one.’ That is, we start with a mental free-for-all of many ideas, and in the end we need to close. Even someone with attention deficit disorder who is very creative ultimately has to sit down and choose the idea to move forward with. There isn’t only staring into space and only focus — there’s a combination.”

If you had to shatter one myth about how the brain works, which would it be?

“There’s a myth that refuses to die, according to which we use only 10 percent of our brain. In fact, our research on mind-wandering helps us understand that the brain is very active even when we’re doing nothing. People go on retreats to try to quiet the mind, and it’s a hard battle. Even when we’re not engaged in anything, our brain is very active, in the shower, in traffic jams. It doesn’t stop.”

And what’s the most exciting discovery you’ve made in your research?

“That if we know where a thought is wandering to, what’s the point of thinking it?” he asks, as if sharing a secret with himself, and immediately answers with an example from his time as a professor at Harvard, from which he returned after 13 years to head the Gonda Brain Research Center at Bar-Ilan University.

“When I was at Harvard, once a year I would travel to a very beautiful place in Florida, where a conference in brain research was held. It was the seventh year I flew to the same conference, and on the plane I was already imagining how I’d arrive at the airport, pick up my suitcase, go get the convertible Mustang, arrive at the beautiful, familiar hotel and unpack, go for a barefoot run on the beach like I love, go out to a restaurant I know and love in the evening, watch a movie in my room and fall asleep. And then I get to the hotel and what do you think happened in reality? I didn’t go anywhere. The simulation was so accurate that I didn’t need to experience any of it in reality. The endorphins in my brain had already been harvested.”