Farmers in the Negev Desert during the Byzantine period, from the 4th to 7th centuries, developed a flourishing wine industry despite the region’s arid conditions, relying heavily on sophisticated rainwater collection systems — according to a new study from the University of Haifa.

The new study published in the scientific journal PLOS ONE, reveals how these farmers achieved remarkable success and why their industry eventually collapsed. Using an innovative computational model, researchers reconstructed the scale of wine production, the conditions behind its prosperity and the vulnerabilities that led to its decline.

4 View gallery

Byzantine agricultural infrastructure in Negev Desert

(Photo: Yotam Sofer, University of Haifa)

“Our study shows how ancient societies adapted to extreme climates and their dependence on maximizing natural resources, offering valuable insights for today’s climate challenges,” said Prof. Guy Bar-Oz of the University of Haifa.

Wine was a highly profitable and sought-after commodity across the Mediterranean throughout history, reaching its peak in the Byzantine Negev. Previous research highlighted the advanced dryland farming techniques used by Negev farmers, such as building terraces, drainage channels, stone dams and storage cisterns to capture and utilize rainwater for irrigating vineyards and fields.

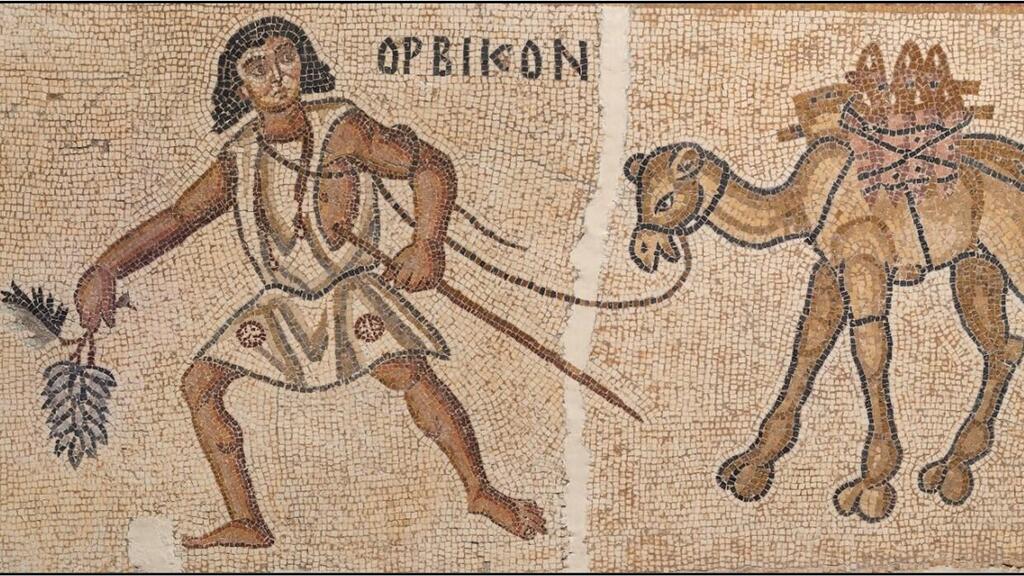

4 View gallery

Byzantine agricultural infrastructure in Negev Desert

(Photo: Yotam Sofer, University of Haifa)

However, until now, no quantitative model had assessed how these methods enhanced yields or how vineyards performed during droughts or extreme climate shifts. The study, conducted by Prof. Bar-Oz, Prof. Gil Gambash, research student Barak Garty from the School of Archaeology and Maritime Cultures and Prof. Sharona Tal Levy from the Faculty of Education’s Department of Learning and Instructional Sciences, explored the resilience of this agricultural system and how Negev farmers sustained a commercial wine industry in the desert.

The researchers developed a unique digitized model integrating archaeological, environmental and climatic data from the Byzantine Negev. The model incorporated details on terrain, soil types, terrace systems and rainwater collection, alongside precise data on precipitation and evaporation.

4 View gallery

Computer simulation of Byzantine wine production in the Negev

(Illustration: University of Haifa)

Through simulations, the team calculated the volume of water reaching the vineyards, estimated grape yields and evaluated how farmers coped with prolonged droughts. “Our model simulates different scenarios, showing what happens to the agricultural system when the climate changes or rainfall drops drastically,” the researchers explained.

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

“It provides a near real-time glimpse into how desert farmers planned their agriculture and responded to extreme conditions.” The findings reveal that rainwater collection and terrace systems enabled Byzantine farmers to produce significant wine quantities even with less than 100 millimeters (3.94 inches) of annual rainfall.

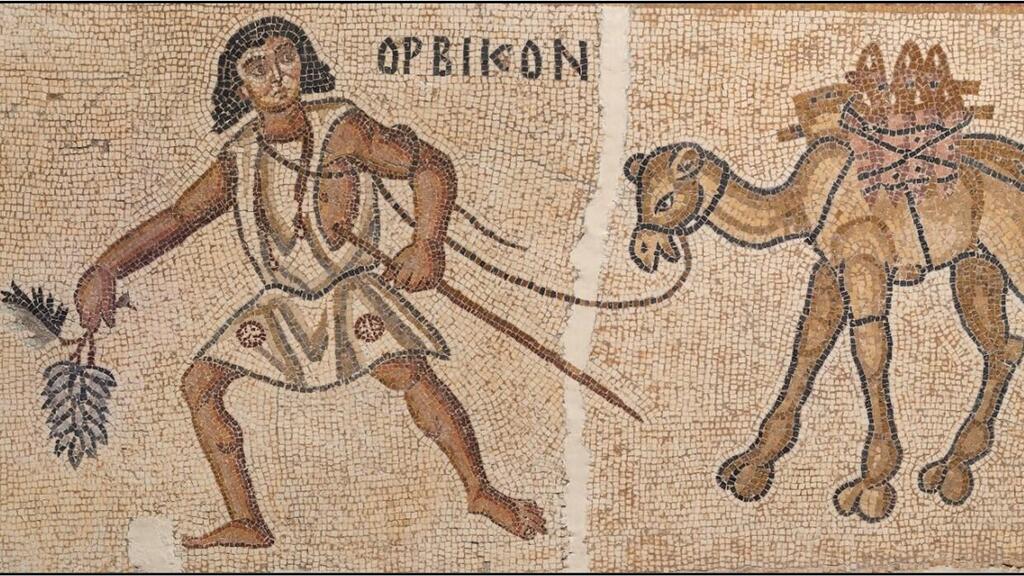

4 View gallery

6th century Bynzantine fresco found in Israel showing grape farmer

(Photo: Israel Museum)

Strategic vineyard placement in wadis increased the success of desert agriculture, which depended entirely on precipitation levels. The model showed that two consecutive drought years reduced wine production by nearly a third compared to average years, while a five-year drought slashed output by over 60%.

Recovery from prolonged droughts could take more than six years, highlighting the system’s fragility. The study underscores the challenges of sustaining agriculture in such a harsh environment and the vulnerability of the Byzantine wine industry to extended dry spells.

“Our findings illustrate the difficulty of desert farming and the system’s susceptibility to prolonged drought,” the researchers noted. “This is a crucial lesson for today, helping us understand the limits of agriculture in arid regions and design systems better equipped to handle climate change.”