Israel is at the forefront of treating Alzheimer’s Disease with newly approved drugs that slow the disease’s progression—but only for patients who can afford the steep price tag. The groundbreaking medications, which are not covered by the national health basket, can cost up to NIS 13,000 (roughly $3,500) per month, leaving most patients without access to them.

Sourasky Medical Center was the first in the country to offer the treatments. “It’s not a miracle but if we can keep people functioning longer—we’ve won,” said Dr. Tamara Shiner, head of the hospital’s Advanced Alzheimer’s Treatment Unit.

3 View gallery

Patient recieving Alzheimer’s Disease altering medication at Sourasky Medical Center

(Photo: Yuval Chen)

Ilana, a 64-year-old patient diagnosed two years ago, started taking Leqembi (Lecanemab) in January 2024, shortly after its approval. “I didn’t care what it was—I just needed hope,” she said.

Today, she still drives, shops and debates politics. Her private insurance covers part of the costs, leaving her to pay about NIS 4,000 ($1,000) monthly out of pocket. “Why is chemotherapy in the health basket and this isn’t?” she asked. “These medications give people their lives back.”

A scientific breakthrough

Recent years have seen a major shift in Alzheimer's treatment. For the first time, medications are available that target the disease’s root cause rather than just easing symptoms. While Israel has an estimated 100,000 Alzheimer’s patients, the new treatments remain outside the public health system due to their cost.

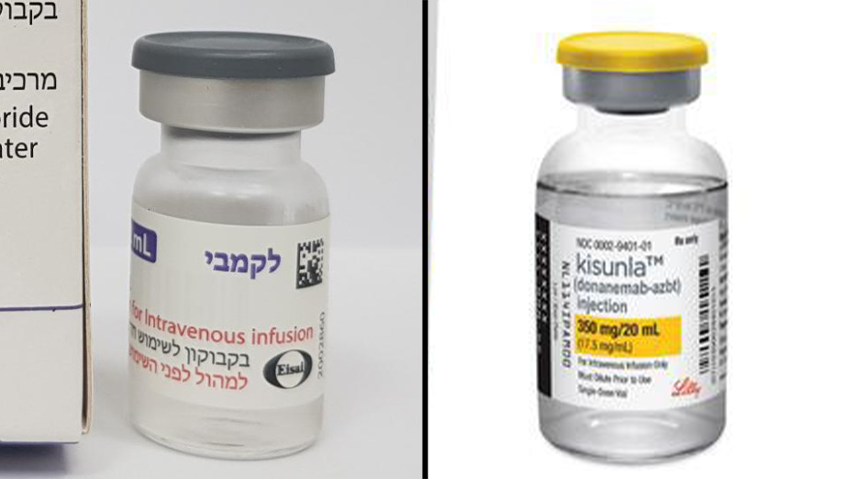

Among the most promising treatments is Leqembi, an intravenous drug administered every two weeks. It reduces beta-amyloid levels in the brain by 60%, and long-term studies show that 50% of patients remained stable over 42 months—compared to just 35% in untreated cases.

Another medication, Kisunla (Donanemab), was approved last year. Given monthly, it delayed cognitive decline by over five months and reduced the risk of advancing to the next stage of the disease by 37%. The third drug, Aduhelm (Aducanumab), received approval in 2021 but is now rarely used due to the superior efficacy of newer options.

“These aren’t miracle cures,” said Dr. Shiner. “But if we can delay the transition from mild cognitive impairment to early dementia, that’s huge—more time living independently, working, even driving.”

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

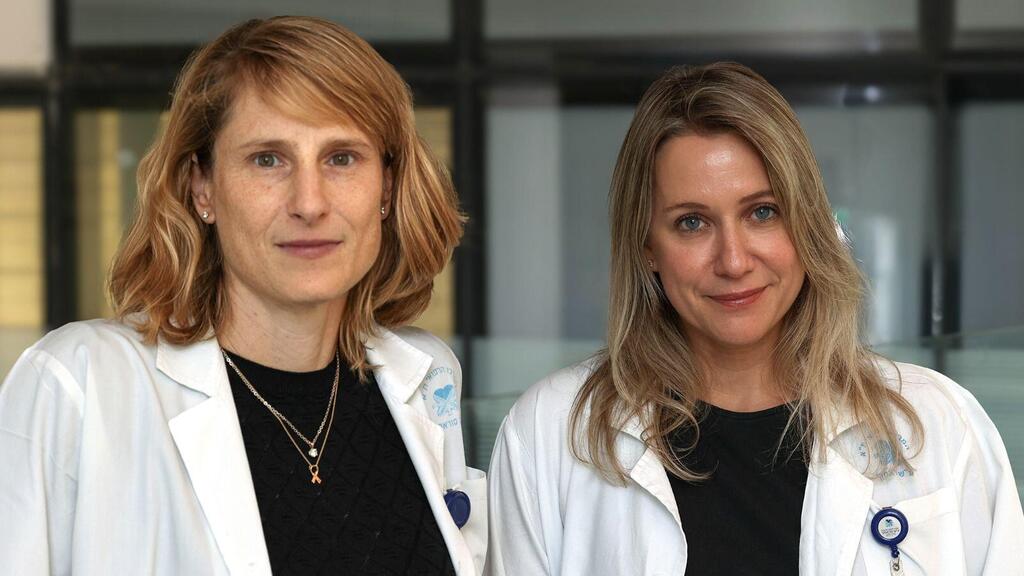

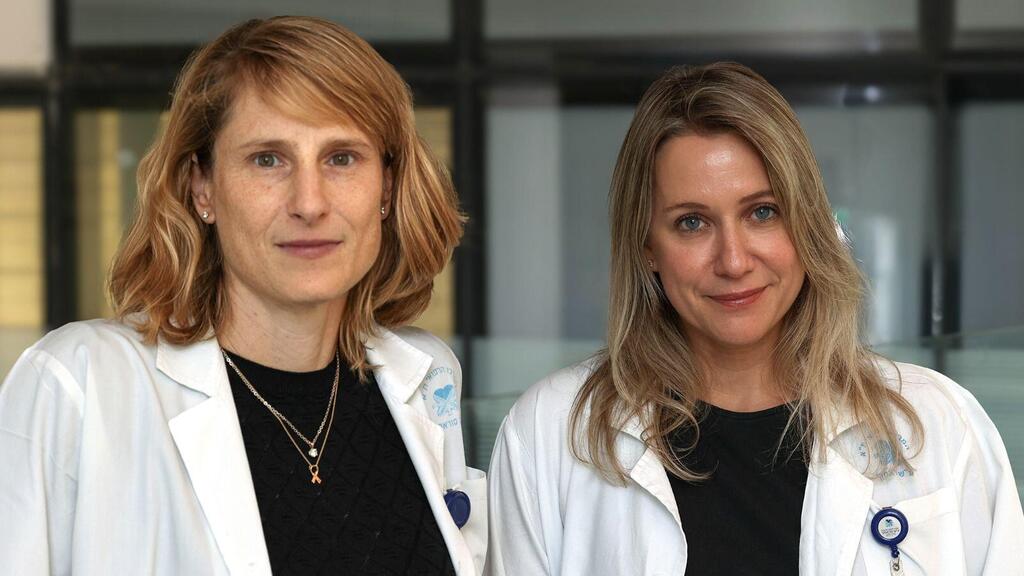

3 View gallery

Dr. Tamara Shiner and Dr. Noa Bergman

(Photo: Jenny Yerushalmi, Sourasky Medical Center)

Hope—at a price

Gabi, 78, was among the first to receive Leqembi at the hospital. After a year and a half on the drug, doctors say his condition has remained stable. “No deterioration means it’s working,” said his wife Mali. “We were shocked the drug wasn’t included in the health basket. It gives people hope.”

Dr. Noa Bergman, head of Sourasky’s Cognitive Neurology Department, said the hospital fought hard to bring the drugs to Israel. “We knew we couldn’t wait—some patients wouldn’t be eligible if we delayed,” she said. The first shipment arrived just two weeks after October 7.

More than 130 patients are now receiving the treatments at the hospital. “We’ve built an entire infrastructure,” said Dr. Bergman, including physicians, nurses and coordinators. But the financial burden remains steep, with monthly costs ranging from $2,000 to $4,000.

“We have cancer drugs in the health basket that extend life by only three months,” she said. “These medications fundamentally change the trajectory of Alzheimer’s—and yet they’re excluded.”

According to Bergman, the Health Ministry still treats Alzheimer’s as a geriatric issue, even though patients in early stages may still work, travel and function independently. “People need to know that those with Alzheimer’s live among us,” she said. “We need to catch the disease in its earliest stages.”

A quiet revolution

Some patients have reported minor side effects; one developed treatable brain swelling. Due to the risk of brain hemorrhage, patients undergo frequent MRIs and those with genetic predisposition are not eligible for treatment.

The drugs are currently offered at several hospitals but Sourasky Medical Center remains the national leader. “These treatments have redefined Alzheimer’s,” said Dr. Bergman. “They’re not the end of the story—just the beginning.”