Between the streets and the layers of history

Every morning—or at least when I manage to—I try to go for a jog. It’s a new habit I’ve adopted since arriving in Cologne about a month ago, as a visiting researcher at the university. My regular destination is the Volksgarten, a quiet green park just a kilometer from the apartment I rented.

My route begins on Quirinstrasse, right by my building. From there, I turn onto Am Trutzenberg, a relatively calm street before the city wakes up. But farther along, as I enter Eifelstrasse, that quiet fades: nearly every building is covered in graffiti of one kind or another. Most of it is simple vandalism—names, symbols, random scrawls—but sometimes there’s also political graffiti, the kind that brings the Middle East to Europe, and to Germany in particular.

9 View gallery

Stolpersteine in memory of Holocaust victims, in Cologne, Germany

(Photo: Dr. Moti Gigi)

Even before I encounter the political colors, another kind of marker appears beneath my feet: Stolpersteine, or “stumbling stones”—small brass plaques embedded in the sidewalk, engraved with the names and life stories of Jews who lived right here before being uprooted in the Holocaust. The project began here in Cologne, when German artist Gunter Demnig placed the first stones in the early 1990s. Since then, they have spread across Europe, each one serving as a personal point of remembrance within public space.

Cologne, the Jews and the stones that remember

Cologne is one of the oldest cities in Germany, with a Jewish history stretching back nearly two thousand years. Jews are mentioned here as early as the fourth century CE, and during the Middle Ages the city was home to a large, thriving community—until the Jews were expelled in 1424. Over the centuries, they returned in several waves, and on the eve of World War II, the city’s Jewish population numbered more than 19,000. Most were murdered in the Holocaust; only a few survived.

Today, Cologne has a renewed Jewish community, but its history has not disappeared. It is embedded in the streets, the stones and the metal around them. The city’s Jewish museum documents centuries of Jewish life, but it’s on the sidewalks, beneath one’s feet, that the most powerful reminder lies: the Stolpersteine project.

These small stones—each just 10 by 10 centimeters—bear brass plates inscribed with the names of Jews who were deported, murdered or forced from their homes. Each stone is placed in front of the house where the person lived, so the sidewalk tells an intimate story: a name, a birth year, a date of deportation or death. More than 90,000 such stones are now scattered across Europe, making this the largest Holocaust memorial project in the world.

It is no coincidence that the project began here, in Cologne. Demnig, who was born in the city, saw it as the right place to raise questions about public memory: What do we choose to remember—and what do we choose to forget? He once said, “One stone is worth more than a thousand speeches,” and the streets of Cologne make his point vividly clear.

For me, as a morning jogger, encountering these stones is almost inevitable. Between one graffiti tag and the next, between a political slogan sprayed overnight and another painted over the following day, the brass letters suddenly gleam: a first name, a last name, a year. These are not words added to a wall, but memory embedded in the ground. In a way, it’s the first dialogue between past and present that I encounter with every run.

Graffiti as a medium of protest – from the Bronx to Europe

Graffiti was reborn in the United States of the 1970s, mainly in the Bronx, New York. Youths—most from marginalized backgrounds—used the walls of subway cars and building facades to mark their presence. In an era when they had little or no access to mainstream media, graffiti became the street newspaper of a new generation. Names, symbols, slogans—sprayed in bright colors and at a fast pace, meant to dodge the police.

9 View gallery

A man sprays graffiti on a preserved section of the Berlin Wall, in Berlin

(Photo: Sean Gallup / Getty Images)

Within just a few years, graffiti evolved from an act of rebellion on the margins to an international medium. In Europe, especially in post–Wall Berlin, the city’s walls became an open laboratory for political expression. The Berlin Wall itself—once a sealed border between East and West—was soon covered in words, images and messages. Many were explicitly political: calls for freedom, peace and human rights. Others were simply personal marks, traces of presence on a wall that had turned into a global symbol.

Since then, graffiti has become an inseparable part of Europe’s urban landscape—a tool of protest and a form of personal expression. The student uprisings in Paris, the anti-globalization demonstrations in Italy, the recent climate protests—all left their layers of paint on city walls. Wherever there’s political tension, graffiti isn’t far behind.

In Germany, graffiti moves between two poles: on one hand, it’s considered vandalism and a criminal offense; on the other, it’s deeply embedded in urban culture. In cities like Berlin, Hamburg and Cologne, it’s almost impossible to find a street without some kind of inscription. Sometimes they’re random—tags, symbols, names. Other times, they’re sharp political messages: against racism, in support of refugees or, as I saw in Cologne, messages tied directly to the Middle East.

The five layers of writing on 'The Wall'

Stage One: Free Gaza

Just after turning onto Eifelstrasse, my eyes catch the words Free Gaza painted in large white and black letters. The slogan repeats again and again—on shopfronts, under bridges, along bike paths. A direct message, almost ready-made for protest. It felt as if the city itself had donned the uniform of demonstration. I couldn’t photograph it right away. When I returned the next day, a group had already added the hostages’ symbol, along with the date “7.10” in yellow paint.

Stage Two: The alteration – 'From Hamas'

It didn’t take long for the original inscription to change. The word Gaza was covered in bright yellow, replaced with the words "From Hamas" in black. A new message was born: Free From Hamas.

Stage Three: Remembering the hostages

On the same wall, new inscriptions appeared: "7.10 Never Forget" and "Free The Hostages." The reuse of the original word "Free," this time with a different addition, altered the meaning once again. The wall became an improvised memorial, a reminder of missing human lives.

But the call didn’t remain only in graffiti. A few streets away, on the facade of the Great Synagogue on Roonstrasse, a huge banner was hung—black, red and white—facing the busy street, carrying the same cry first sprayed on a gray wall. This was no longer an act of rogue protest but an official communal statement. The Jewish voice in the city amplified what the graffiti had already begun to say: that the struggle is not only over land or borders, but over human lives held captive.

9 View gallery

A banner calling for the release of hostages held by Hamas hangs on the facade of the Great Synagogue on Roonstrasse in Cologne, Germany

(Photo: Dr. Moti Gigi)

Stage Four: From black to bronze

Even that wasn’t the end of the story. The inscription "From Hamas," first written in black, was later covered again—this time replaced by "From Israel" in bronze-gold letters. The shift from somber black to a gleaming metallic tone seemed to express a desire to give anti-Israel messages a more permanent, enduring presence.

Stage Five: The quiet erasure

In one case, an entire building facade was covered in graffiti—layers of colors, slogans and competing claims. But the residents refused to serve as a platform. Within days, everything was painted over, and the wall returned to a clean state.

9 View gallery

A building wall in Cologne, Germany, after graffiti was removed amid ongoing exchanges of political messages

(Photo: Dr. Moti Gigi)

It may have been the quietest political statement of all—not taking a side, but refusing to be a stage. In a way, it mirrored the digital world: like on Facebook, when group moderators decide a post has crossed the line—and simply delete it.

From the digital wall to the physical one and back again

What’s happening on the walls of Eifelstrasse in Cologne mirrors almost exactly what happens on Facebook or on X (formerly Twitter). Someone posts "Free Gaza." Someone else comments and reframes it "From Hamas." Another adds new context "7.10 – Never Forget, Free the Hostages." Then comes a counter-response "From Israel." Finally, the post is deleted—not by one of the participants in the argument, but by the building’s owners, acting like moderators who decide the thread has gone too far.

The wall functions like a live feed: it changes daily, retains traces of earlier posts and remains visible to everyone passing by. But unlike Facebook, there’s no true Delete button here. Every erasure becomes a new layer, every edit leaves a mark. The public space turns into a vast screen where each side tries to claim the narrative—not just with words, but with colors: white against yellow, black against bronze.

Research, polarization and a global echo

My presence here in Cologne isn’t accidental. I’m here as part of a joint research program between Sapir College and TH Köln, studying polarization in Israel and Germany after October 7. We’re exploring how division is reflected in traditional media and on social networks. Of course, the polarization didn’t begin then—but the events of October 7 amplified it dramatically, creating a wave that still reverberates today.

In that context, the connection between three arenas—the Stolpersteine of the past, the graffiti walls of the present and the “walls” of social media—creates and amplifies a tangible memory that speaks to today’s intertwined Israeli and global realities. In each of these arenas, a constant debate unfolds: about memory, identity and narrative. Each reveals how the divisions here—in Cologne, in Israel and in digital space—reflect the same global fracture that refuses to fade.

From Cologne to Berlin: The narrative continues

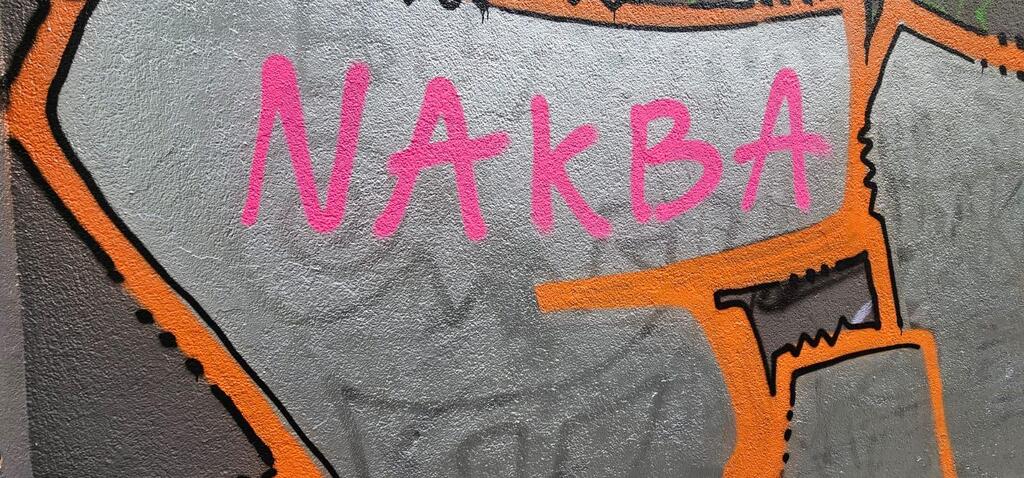

As part of our research, my German colleague and I presented our initial findings at a conference on Israel held in Potsdam. Before returning to Cologne, I stopped in Berlin for a night, staying near Rosa Luxemburg Platz. There was something both symbolic and ironic in what I saw there: on a gray wall, in bright pink letters, the word "NAKBA."

The symbolism was almost overwhelming—graffiti invoking the Palestinian catastrophe on a street named for Rosa Luxemburg, a Jewish woman who fought for social justice and was murdered in 1919 by conservative forces. With all the painful, bloody history of Jews in Germany, this new graffiti constructs a reality in which Jews are not the victims of catastrophe, but the cause of one for the Palestinian people.

Conclusion: The past, the present and what comes next

So, on my daily running route—which repeats itself each morning, as I’ve mentioned—I move between layers of time, space and meaning: from the Stolpersteine that return Jewish history to Cologne’s sidewalks, to the ever-changing graffiti that brings the Middle East into the heart of Europe, to the blank facades wiped clean in the name of domestic calm.

It raises many questions. I often wonder what someone like Helene Berlin—born in this very neighborhood in 1884, deported in 1941, and officially declared “no longer alive” (Für tot erklärt)—would say. What would she and the many Jews whose lives were cut short think of today’s graffiti, of Israel’s place in the world, of a war nearing its second year, of the hostages, of how Israel is perceived in Germany now?

This is a space where past, present and future meet anew every morning. The open question is how Europe’s public sphere will look in the coming years: will it remain an open battleground of colorful slogans, or become a censored space that erases layers, messages and debates—much like what happens on social media?

As I finish my jog and turn back home, I pass the same walls again. The changes are small—a new inscription here, a partial erasure there—but enough to remind me that the struggle over narrative isn’t confined to the Middle East. It’s right here, in the heart of Europe, on sidewalks engraved with the names of murdered Jews.

In a month, I’ll finish my stay here and return to Israel. The graffiti will remain—changing, fading and reappearing. The stones will stay fixed in the pavement. The larger question—how Europe chooses to confront both its history and today’s Israeli-Palestinian reality—will continue to echo with every step along Germany’s streets.

- Dr. Moti Gigi is a sociologist and senior lecturer in the Communication Department at Sapir College, and a visiting researcher at TH Köln in Cologne.