In Parashat Vayigash, we transition from the high drama of Joseph’s emotional reunion with his brothers to a detailed account of his economic management of Egypt during the seven years of famine. The Torah describes how Joseph collected all the money, then the livestock, and finally the land itself for Pharaoh in exchange for bread. This unusual focus led R. Don Yitzchak Abarbanel to ask why the Torah elaborates so much on what seems like the secular administrative chronicles of Egypt rather than the divine instruction of God.

The debate over Joseph’s policy

Interpretations of Joseph’s economic strategy vary significantly. Some, like the French Tosafist Rabbi Joseph Bekhor Shor, view Joseph’s actions critically. They argue that since Joseph had collected the grain as a tax during the years of plenty, he should have distributed it for free during the famine. This "nationalization" of all property and money—while Joseph’s own family received food for free—is seen by some as a catalyst for the resentment and antisemitism that would eventually lead to the enslavement of the Israelites.

However, a different perspective suggests Joseph acted with great wisdom by using money as a tool to manage and limit consumption. By charging a normal price rather than a famine price, Joseph ensured that the storehouses would not be stormed unnecessarily and that food would not run out prematurely. Much like modern welfare allowances, distributing necessities for free can lead to corruption, fraud and manufactured "needs." In times of crisis, free distribution often descends into chaos and social unrest, as people feel the distribution is unjust or engineered by insiders.

Trust and professionalism in crisis

Why did the Egyptian masses accept these policies without rising up? History shows that revolutions, such as the French Revolution, are often the result of mass food shortages. Joseph and Pharaoh maintained order by fostering a culture of trust and transparency. When the people cried out to Pharaoh, his response—"Go to Joseph"—was a masterstroke of political management. It signaled that there was an orderly plan prepared years in advance and that the system was led by a responsible professional. Furthermore, Joseph’s status as a foreigner, unaffiliated with any specific internal Egyptian faction, may have helped quiet local anxieties about favoritism.

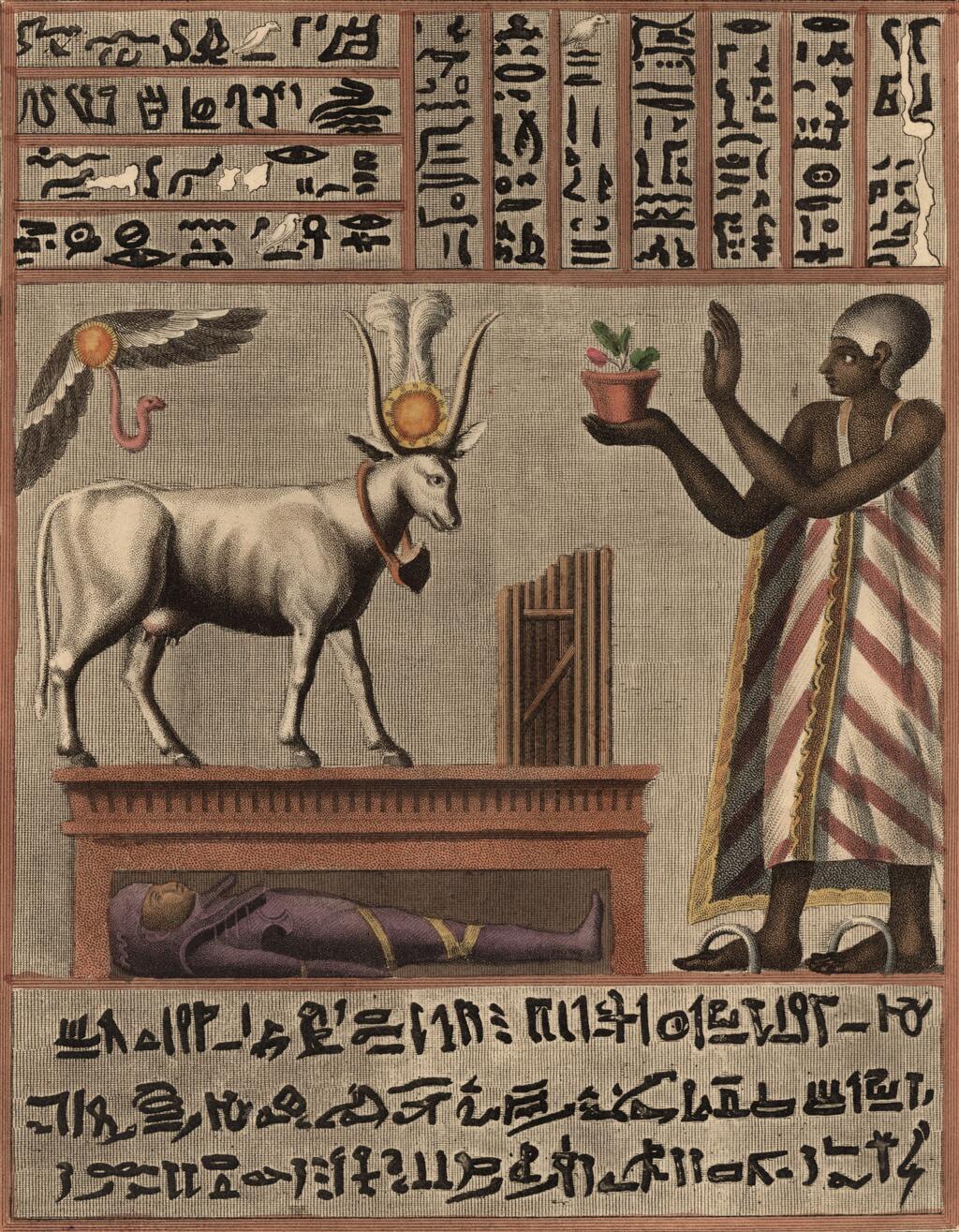

The strategic value of livestock

When the money was exhausted, Joseph pivoted to a policy of exchanging livestock for bread. On the surface, this might seem like a poor deal for Joseph; he was trading precious food for starving animals that would now become a "cash-flow sink" for the government to feed. This desperation to save livestock is echoed in the later story of King Ahab and Obadiah, who searched the land just to keep their horses and mules alive during a drought.

However, for Joseph, this move was a strategic success. By taking in the animals, he signaled to the markets that the king’s storehouses were so abundant that they could sustain the entire nation’s herds. This projected a sense of calm and optimism. Moreover, this consolidation allowed for long-term "alpha". Researchers note that around this era, Egypt developed royal stables and sophisticated horse-breeding programs that turned the nation into a regional military power. By centralizing the livestock, Joseph enabled experimentation and the cultivation of superior genetic traits, reinvigorating the nation's herds.

Leveraging family talent

To manage this massive project, Joseph looked to his family. Pharaoh offered Joseph’s brothers roles as "chiefs over my livestock." This was not mere nepotism; the brothers were experts in shepherding, carrying on the sophisticated knowledge of their father, Jacob. Jacob had famously used his understanding of animal mating and genetics to build his own prosperity years before. Joseph integrated this family expertise into the Egyptian state, ensuring that the economy would return to its pre-famine state even more powerful than before.

Modern takeaways and the vision for the future

Joseph’s management offers profound lessons for modern economics. One of the great challenges for democracies today is long-term investment. Unlike authoritarian systems that can finance projects with 50-year horizons, democracies often focus on short-term electoral cycles and immediate welfare distribution. Conversely, overly planned economies can dull the entrepreneurial spirit, leaving nations a step behind in innovation.

Joseph found a balance. He built the infrastructure and storage reserves necessary for survival, but he also eventually returned initiative to the people. When he finally gave them seed to sow the land, he emphasized that it was an investment: "for seed for the field" came before "for your food." He trusted the citizens to think about their children and grandchildren, emphasizing that private initiative ultimately benefits the entire state.

Ultimately, Joseph’s story is one of optimism and the human ability to influence nature through transparent management and long-term vision. By looking beyond the immediate crisis and building a complex, intergenerational "function," Joseph transformed a period of death into a foundation for a great power.