Is posting a selfie from Auschwitz‑Birkenau on social media an act that dishonors the memory of the Holocaust victims — or one that honors them? It seems that, as with many things, the answer depends heavily on the context and the style.

“When young people take selfies in Auschwitz, it is not much different from Israeli politicians who ask a professional photographer to shoot them there,” says Professor Jackie Feldman, chair of the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at Ben‑Gurion University of the Negev. In a new study, he connects the impending loss of the last Holocaust survivors with a growing trend among youth: the need to document themselves, even at places where many of their people were murdered.

“Twenty‑five years ago, my doctoral work focused on youth trips to Poland,” Feldman said, “I argued that this was a kind of pilgrimage for a civil religion, and what mattered was not the trip or the speeches the students heard — but how you shape the space, the time, the rituals and the sense of security. From interviews with the teens, I learned that what was most important to them was to touch death, and come back feeling more Israeli, or more proud as a Jew. The destruction of Polish Jewry and the humanitarian story weren’t really important to them.”

At the time, there were no smartphones and selfies were impossible.

“But there were cameras,” Feldman recalls. As part of preparing students for the trip to Poland, he had asked them to leave their cameras on the bus, saying: ‘Remember — you are not the eyewitness.’”

What was the reaction?

“There was an outburst of revolt. Both the students and the teachers protested. Their message was: once we take pictures and show them to others, we feel that we fulfilled the commandment of bearing witness — of being ‘witnesses of the eyewitnesses’.”

5 View gallery

President of Israel Isaac Herzog alongside Polish President Andrzej Duda, at the March of the Living in Auschwitz

(Photo: Kacper Pempel/Reuters)

Since then, a lot has changed — among other things the rise of social media.

That context gives another dimension to what’s happening. For example, more than a decade ago, the satirical Facebook page “Me and my beauties at Auschwitz” sparked controversy.

In light of that, Feldman says that, although little has changed in 30 years regarding how youth view Holocaust memorial trips, there are three major differences now.

First, in earlier years these trips were accompanied by firsthand witnesses — Holocaust survivors — but most have since died or are too frail to travel. Second, nowadays there are no surprises — participants know exactly what they will see and where they'll be photographed.

Third, the rise of social media and smartphones has unleashed a flood of images, shared in all possible media — even on dating apps or places like Grindr.

“People post selfies to appear ‘cool,’” Feldman says.

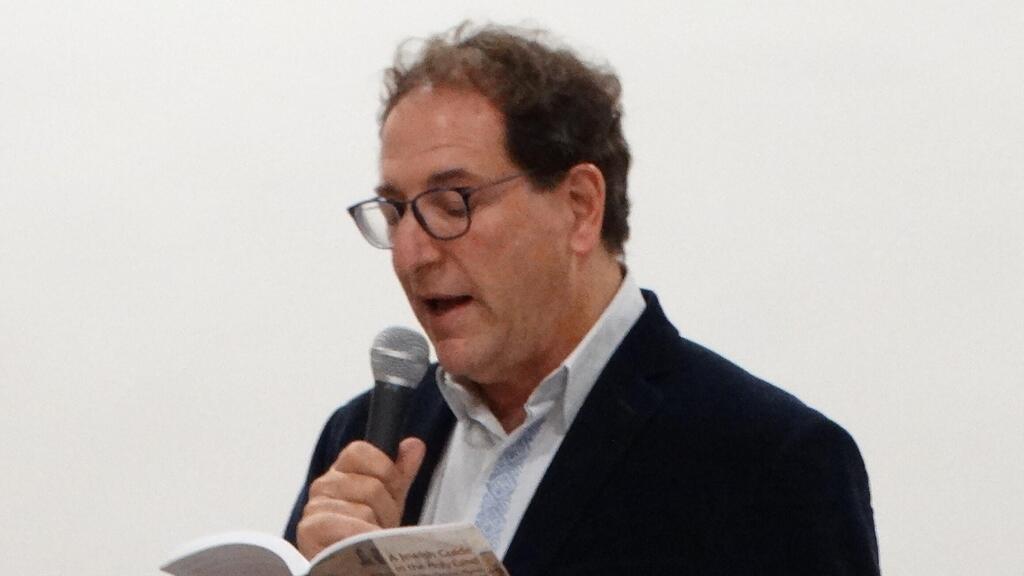

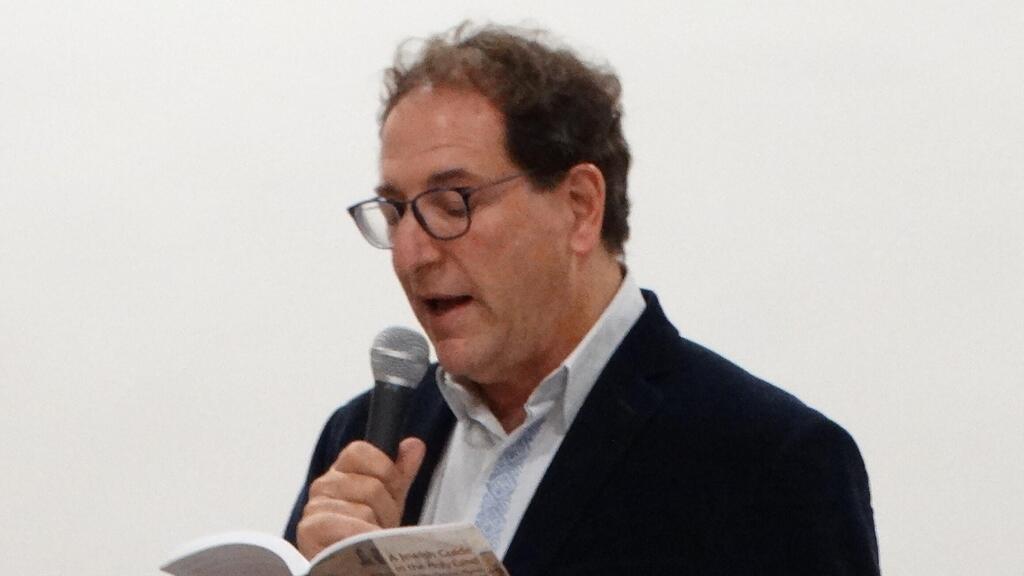

5 View gallery

Professor Jackie Feldman: 'Even when 'Schindler's List' was released in theaters, there were many who harshly attacked it'

(Photo: Private album)

Can anything be done about it?

“When 'Schindler’s List' was released in theaters, many – including Eli Wiesel and Claude Lanzmann – criticized it harshly. Today almost every institution acknowledges the film’s contribution. For selfies — Auschwitz management tried to distinguish between a ‘respectful selfie’ and a ‘disrespectful selfie.’ They said: we can’t prevent it, but let’s display on our website what we consider respectful poses — serious expressions — versus what we don’t consider respectful. Then the public will respect those who shoot respectfully, and will criticize those who post, for example, a balancing act on the train tracks.”

Feldman also recalls the photographic project of Israeli‑German artist Shachak Shapira. As a protest against what he perceived to be a trivializing “selfie culture” at the Berlin Holocaust memorial, Shapira began replacing backgrounds in selfies with photographs of Holocaust atrocities, demanding those who posted disrespectful selfies to apologize. “For a while it worked, but today attempts at censorship online are almost powerless,” Feldman says.

'Men get fewer negative reactions than women'

As part of his research, Feldman examined hundreds of photos, posts and responses on social media, and conducted interviews with young people around the world. The results were presented recently at a joint research workshop of the Leo Baeck Institute in Jerusalem, the Holocaust memorial center Yad Vashem, and the Rav Center for Holocaust Studies at Ben‑Gurion University, marking 70 years of the institute’s existence.

5 View gallery

Auschwitz site administrators tried to distinguish between 'respectful selfies' and 'disrespectful selfies'

(Photo: From social networks)

“Over 70 years since its founding, the Institute has been an academic home for researchers studying Jewish heritage of the German‑speaking world," Dr. Sharon Livne, deputy director of the Baeck Institute, said. "We pride ourselves on documenting and researching the history and culture of German‑Jewish communities, including Holocaust memory and archival legacy. At times when Jewish and Israeli identity face crossroads — questions about home, immigration, nationality and state — the institute remains an important knowledge hub.”

Feldman argues that the Auschwitz selfie is part of a broader phenomenon — using the “self” as a mode of seeing and being seen. “If you didn’t photograph it, didn’t post it then you didn’t exist. Everything must be transparent, even what was not meant originally for public eyes. History must become personally relevant.”

He adds: “Since the 1980s, youth trips to Poland emphasized photography and the idea that visitors become ‘witnesses of the eyewitnesses.’ The selfie is a direct continuation of that — the witness becomes the medium. While it is hard to learn about trauma just through a selfie, one can learn about identity, belonging, and how young people view their place in history and politics.”

Is there a difference in how selfies are received?

“A man receives far fewer negative comments than a woman posting the same selfie,” Feldman notes. “Although there’s no difference between a personal snapshot and a politician’s portrait taken by a professional, a selfie taken in front of Auschwitz, with a serious face and horizon behind them, seems to the public like something natural.”

5 View gallery

The March of the Living in Auschwitz. The number of Holocaust survivors remaining alive is decreasin

(Photo: Wojtek RADWANSKI / AFP)

The number of Holocaust survivors alive today continues to decline, and their passing has a major impact on how the Holocaust will be remembered. “Since the 1980s, knowledge was mostly passed down by survivors: they told their stories in ceremonies and memorial sites, visited schools, and later joined the ‘Memory in the Living Room’ project. Since the younger generation will hardly ever meet survivors, they obtain information via social media and media representations. For this generation to absorb the memory effectively and meaningfully it must pass through emotion, it needs something intimate,” Feldman explains.

He argues that in the past, intimacy came through direct contact with survivors, people the young met and who became living witnesses. As those survivors disappear, documentation has moved to photos, video, Facebook, and now the selfie.

“Today’s youth are the next generation of Holocaust memory bearers," he says. "Digital media isn’t just about selfies — it offers new ways to transfer memory: interactive conversations, even holograms of survivors who are gone. Even a single selfie of a friend who visits a Holocaust site can transform the Holocaust into a personal, relevant topic.”