Of the homes that made up the beautiful Kibbutz Be’eri before October 7, only one house will remain standing — the home of the Dvori family. Kibbutz members voted to preserve the family’s house for at least the next five years as a memorial to the massacre the community endured on that Black Saturday. All the other burned homes — scenes of murder, abduction and atrocities — will be demolished and replaced with new houses. In the future, the Dvori family home, or parts of it, will also be relocated to a memorial site for Be’eri’s victims. For now, it will stand in the kibbutz as the sole remaining testimony.

The house is completely burned, breached through the walls, windows and roof, yet we closed the front door behind us out of sheer habit, devoid of logic. Despite the devastating sight, the reasons the house will not be demolished rest on two main factors. First, it is a corner house at the edge of the Carmela neighborhood, which, along with the Olive Grove neighborhood, was a focal point of the Hamas infiltration. The house directly borders the kibbutz’s wheat fields, meaning that when residents return to Be’eri in the near future, the single burned house left standing will not be part of their daily landscape and will not, God forbid, constantly trigger memories and trauma that will accompany them for the rest of their lives.

6 View gallery

The Dvori family home in Kibbutz Be’eri before Oct. 7

(Photo: Courtesy of the family)

Another reason is that the Dvori family was not at home on that terrible Saturday. They were vacationing abroad and were spared the brutal terror attack that invaded what had been their home. Yogev Dvori, 52, and his wife Yael, 49, were in Cyprus with their four children — Zohar, 20; Tomer, 18; Roni, 15; and Adi, 13. “Two days before the massacre, we left for a short vacation in Paphos,” Yogev Dvori says. “As a family, we did not experience the traumatic event that Saturday. Each of us left with a small carry-on suitcase, and that is basically what we have left. From the house we salvaged just a few items, mainly sentimental ones, like a photo album and a Bible I received at my bar mitzvah.”

The terrorist squads that infiltrated Kibbutz Be’eri first stormed the front row of houses, doing whatever they pleased. The Dvori family home was among the first they broke into, and when they realized no one was there, they poured accelerants inside and set it on fire. From there, they continued their rampage of murder and destruction throughout the kibbutz. Inside the house, the living room, kitchen and bedrooms were destroyed. The reinforced safe room was damaged the least, along with the few items it contained.

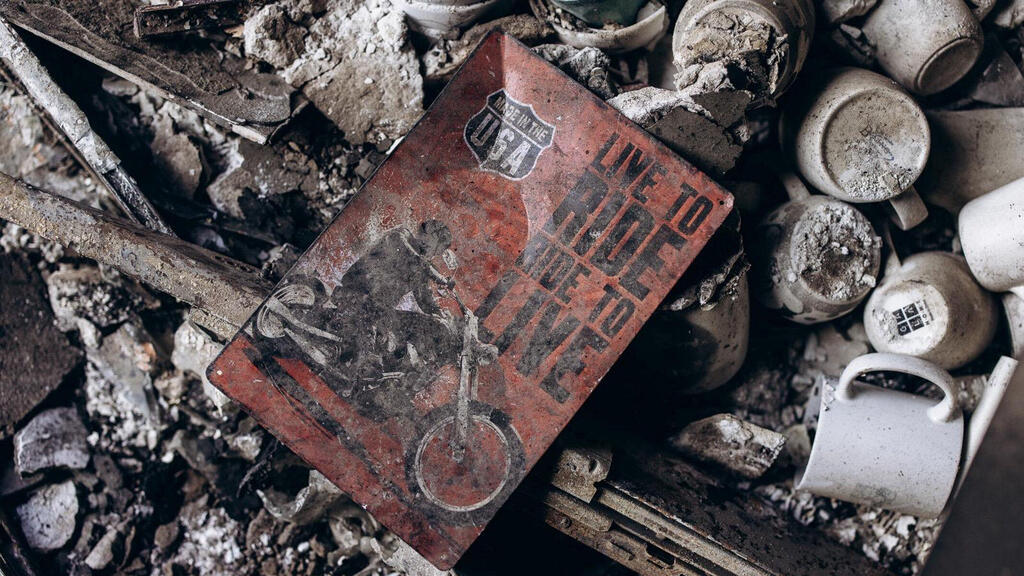

6 View gallery

The destruction inside the Dvori family home in Kibbutz Be’eri

(Photo: Micha Brickman)

The decision to preserve a single house in Be’eri was made about a month ago, after fierce and painful disagreements within the community, most of whom are now living in temporary housing at Kibbutz Hatzerim. Some members believed none of the burned homes should be demolished, others thought several should be preserved, while some argued everything should be torn down and rebuilt. In the end, members decided only one house would remain: 196 voted in favor, 146 against. “I don’t want our kibbutz to look like Auschwitz,” Dvori says. “We need to look ahead, toward the future. There are dignified plans for commemoration, but our kibbutz — for all Be’eri residents — must be rebuilt.”

More than 130 homes in Kibbutz Be’eri will be demolished to make way for new construction. The Dvori family home will not stand in its place forever either, as the state has promised it will be relocated. Dvori remains skeptical. “I don’t see how they’ll manage to move our house,” he says this week. “There’s nothing left of it. Everything here is about to collapse.”

6 View gallery

The destruction inside the Dvori family home in Kibbutz Be’eri

(Photo: Micha Brickman)

He and his family are expected to move into their new home in a different neighborhood of the kibbutz sometime in 2027. In the meantime, alongside rebuilding homes and bringing residents back, the kibbutz is working on a broad memorial plan. “We debated the issue of the burned houses extensively. The disagreements are behind us,” says Gal Cohen, secretary of Kibbutz Be’eri. “For some people, leaving a burned house felt threatening; for others, it triggered nightmares. Everything is understandable, and everything has been handled with maximum sensitivity. We held several rounds of voting and decided that in Be’eri, we would not preserve burned houses within the kibbutz. The one house that will not be demolished will be relocated for a museum the state plans to build in the future. We have a large memorial plan that includes many elements — for example, a memorial house in the kibbutz with valuable items. Everything is documented and preserved — photos, testimonies and videos — so preserving burned houses is only one part of commemoration. In the end, we reached what we believe is the most reasonable solution.”

6 View gallery

The destruction inside the Dvori family home in Kibbutz Be’eri

(Photo: Micha Brickman)

When the issue came to a vote, Dvori was among those who felt there was no point in leaving burned houses standing. “My position was that everything should be demolished and no trace left,” he says. “Not to turn the kibbutz into Auschwitz or a pilgrimage site for visitors. Simply erase everything and commemorate the people we lost, not buildings. There was a very stormy debate in Be’eri, but there was also a desire for renewal — not to dwell on the past, but to focus on the future.”

Did dealing with this make things harder for you and other residents?

“We’re more than two years after the disaster and still dealing only with this. There isn’t a single day in Be’eri when October 7 isn’t mentioned or talked about. Not one day. It’s exhausting. I want to be past this — to be at the stage of building a new home and returning here, to the kibbutz where I was born and that I love.”

And now your house will be the only one left standing and become a symbol. How does that feel?

“From the first day, we didn’t mind people entering our house, because we didn’t experience a traumatic event there. Once we realized there was nothing left to save, we didn’t really care about the house itself. As far as we’re concerned, the door can stay open — anyone who wants can come in, photograph, do whatever they want. It became a kind of exhibition house. Anyone who wanted to see burned houses came into ours. That chapter is behind us now.”

How did it feel the first time you entered your home after Black Saturday?

“It was a complete shock. The kids went in and were stunned — it wasn’t simple at all. We lived in that house for four years, but the greatest pain was for our friends and neighbors. Everyone around us was murdered. The Bira family lived behind us — everyone there was killed except their son, Yahav.”

Did you and your wife agree to leave the house standing?

“My wife didn’t care what would happen to the house — for her, that place was erased. I didn’t object either, and eventually the kids came to terms with it. They approached us because we didn’t experience the trauma that Saturday, and from the entire Carmela neighborhood, it was easiest and most natural to turn to us. That’s completely fine.”

6 View gallery

Yogev and Yael Dvori in their burned home, which will remain standing in Be’eri

(Photo: Micha Brickman)

The Dvori family is one of the largest and most veteran families in Kibbutz Be’eri. Yogev and his four siblings — Eyal, Bosmat, Tsahi and Talia — all live there. Their parents, Avraham (Mancher) and Nurit Dvori, are longtime residents; Nurit’s parents were among the founding generation that settled the area in 1946 as part of the establishment of the 11 Negev settlements.

Mancher previously served as head of the Eshkol Regional Council, as kibbutz secretary and as a central figure in Be’eri and the surrounding area. Yogev’s brother Eyal runs a school in the Eshkol council; brother Tsahi is known locally for founding Be’eri’s pub; and Yogev manages the kibbutz’s motorcycle repair shop.

Every year, the family gathers for a joint trip. Usually, it’s within Israel, but fate had it that in 2023, they chose a three-day stay at a small resort village in Paphos, Cyprus. Their planned return was Saturday, October 7, in the afternoon. “There were 25 of us altogether — children, grandchildren, the whole clan,” Dvori says. “No one ever skipped our family vacations. Everyone came.”

Then the sirens began sounding in their beloved kibbutz. “We woke up in Cyprus to the sound of the app — ‘red alert,’” he says. “We told ourselves it was something routine, you know, living near Gaza. But it didn’t stop. We went down to the lobby and met other Israelis who started sharing what they had heard. Then calls came from relatives checking if we were alive. That’s when we realized something was happening in Be’eri. At the same time, images of burning houses began to arrive. In the photos, we saw that my brother Eyal’s house was the first to burn.”

In those moments, they understood nothing would be the same. “Our return flight was canceled,” Dvori says. “That day we couldn’t eat — nothing went in. We were in complete shock. We went to Larnaca and waited for the last flight to Israel, arriving the next day, when the scale of the disaster made it clear we couldn’t return to Be’eri. In Israel, we scattered, and after a few days, we all met at a hotel at the Dead Sea.”

And still, you didn’t get to say goodbye to the house?

“First of all, we came back with nothing — just flip-flops and a few T-shirts we’d taken abroad. In the first week, donated clothes were brought to us at the hotel. Later, we entered the house only to retrieve items with emotional value, like a family photo album that was completely blackened. To this day, we can’t keep it in our current home because it reeks of smoke, so it’s stored in a warehouse. The Bible I received at my bar mitzvah, which we took from the safe room, I gave to Rachel Fricker, the synagogue caretaker in Be’eri. She restored it, and when she saw me with it, she said, ‘It’s from heaven — it protected you.’ Others told me, ‘Look at the miracle, you should start going to synagogue now.’ Everyone takes it differently.”

The homes of four of the five Dvori siblings went up in flames that cursed day. While Yogev and his family were in Cyprus, reassuring neighbors who called after seeing their house burn, only one family member remained behind, and their thoughts were with her. “What worried me most was our dog,” he says. “The entire Carmela neighborhood burned down, and we didn’t expect to have anywhere to return to, so at that stage we were worried about the dog. She was at a kennel in Kibbutz Gvar’am, also near Gaza, and needed to be rescued. She was in real distress, like all the dogs there. On Monday, Oct. 9, I picked her up, drove to Be’eri to collect two other rescued dogs and loaded them into the car. I managed to enter the kibbutz, but it was impossible to reach my house or the Carmela neighborhood — the fighting there was still ongoing.”

Of course, being abroad saved you, but even knowing your house was burning isn’t easy. What was going through your mind?

“In the first hours, people didn’t yet know we were abroad. When we arrived at the evacuee hotel in Israel, people hugged us and said, ‘What, you’re alive?’ Everyone thought anyone who lived in the Carmela neighborhood had been murdered or kidnapped. Our house was literally the front line by the fence where the terrorists broke through.”

Did you talk among yourselves about the incredible luck?

“Of course, we thought about the fact that we were saved by a miracle. It was more present in the first months; today, we talk about it less. In almost every age group of our children, someone was murdered. We’re all being treated at resilience centers, but we didn’t experience the trauma of those who were here, locked in safe rooms for hours. We don’t compare ourselves to those who were here. But we lost very close friends. Yonat Or, of blessed memory, was my classmate — we were together from two weeks old in the infant house, like siblings. Eli Sharabi was in my group. Avidad Bachar, who lost his family and was wounded himself, is also a close friend. Everyone here is like one big family.”

You come from a deeply rooted family, connected to Be’eri, to the land and its history. Is that what made you certain you would return?

“My father, for example, is very extreme in his views. He thought moving to Hatzerim was a mistake and believed we should have returned here a year ago. But he’s in the minority. I can understand the other side — the trauma, the need to give everyone time and be as sensitive as possible. Personally, I would have been happy to be here from day one. I didn’t feel mentally incapable of being here. I suffer more as a refugee.”

The rehabilitation of Kibbutz Be’eri runs through the rehabilitation of its residents, who are trying to return, as much as possible, to who they were before. Dvori is a mechanic by trade, and shortly before the massacre, he opened a motorcycle repair shop in the kibbutz. Most of his clients are from the area, so business has not returned to full operation, and the effects of Black Saturday are still felt there.

6 View gallery

The destruction inside the Dvori family home in Kibbutz Be’eri

(Photo: Micha Brickman)

“We lost Noy Shosh, of blessed memory, who managed the shop,” he says. “We also lost Shmulik Weiss, of blessed memory, who was the shop foreman. One of my mechanics from Kfar Aza, Yaniv Ohana — who was also the drummer for singer Pe'er Tasi — was seriously wounded and hasn’t returned to work. Our receptionist lost her brother, Ran Shefer, of blessed memory, who was murdered at the Nova music festival. And our storekeeper, Kobi Ben Ami, is the brother of Ohad, who was kidnapped and later returned from captivity. All of us at the shop are living through the disaster. In the days after the massacre, more than 100 kibbutz vehicles stood here, which we had to move to the Dead Sea hotel because residents were paralyzed. This is a kibbutz — residents don’t have private cars.”

And today, is there a livelihood?

“The business is still down, and we’re inviting customers from all over the country to come to us. That Saturday, we lost about 100 regular customers — residents of Nahal Oz, Kfar Aza, Nir Oz and other communities. We have a system to send messages to customers, and I remember sitting there and simply deleting the names of customers who were murdered. There are also those who survived but haven’t returned to the area. We lost them, too.”