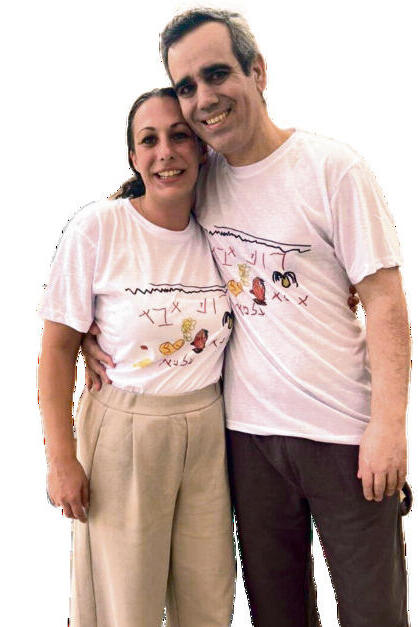

Two weeks after Omri Miran returned home to his wife, Lishay, and their two daughters, the first outburst came. Roni, 4.5, shouted at him: “Go to Gaza! Go back to Gaza!” Even now, two months after the family of four was reunited in a temporary home at Kibbutz Kramim, Lishay says she still can’t claim that life has returned to normal. In her view, they are all still at the beginning of a journey, made up of fleeting moments.

“There are days when we all wake up in a good mood and have the most amazing day together,” she said. “And then there are days that are completely different. The recovery process includes moments of regression, followed by rebalancing. That’s natural and human.”

Just a few days ago, 2.5-year-old Alma got upset with Omri and declared, “This is Roni, Alma and Mommy’s house.”

“I told Alma it’s also Daddy’s house, and she said, ‘But he came later.’ I told her, ‘You’re right, Daddy came here after us, but he’s not going anywhere. He’s here.’ That’s something I remind them all the time.”

And what did you say to Roni when she “sent” her father back to Gaza?

“I didn’t step in because it resolved itself within a minute. Omri told Roni, ‘I don’t want to go back to Gaza. I didn’t have fun there.’ She thought for a few seconds and said, ‘Right, it wasn’t fun. You were with bad people,’ then ran over and gave him a hug. On the other hand, when Omri goes into catch-up mode and wants to hear every missing detail right away, I tell him, ‘Wait, there’s no rush. The girls and I aren’t going anywhere. You’re not getting rid of us that easily.’”

For two years, she was singularly focused. “I understood that I had two roles in this world—to be the wife of and the mother of—but not to be Lishay in any way. I completely lost myself, and now I’m in the process of finding my way back. I need to rediscover and understand my own path in the world. I wasn’t held captive by Hamas, but I was in a different kind of captivity—a psychological one—and getting out of it also requires a long recovery.”

Now, the family is celebrating—or at least marking—many “firsts” together. “The first time Omri walked toward the car, Alma gave him a strange look and asked, ‘Why is Daddy driving? Mommy drives.’ I told her Daddy can drive too, but she insisted, ‘No, that’s Mommy’s job.’ She was only six months old when her father was kidnapped. She grew up with a father in photos, and then one day, he just appeared in her home. I have no doubt she asked herself who this man was.

“For both of them, the bed in the master bedroom was Mommy’s and theirs. It took time for them to get used to the idea of Daddy being in Mommy’s bed. Thankfully, that phase passed quickly. Now, they climb into our bed in the middle of the night without hesitation.”

Do you document your family's “firsts” together?

“That’s a good idea, but I’m not documenting reality—I’m busy living it. You know, when I stood in front of the three of them with tears in my eyes like a little girl? When he made pasta sauce with them. Just pasta sauce, right? Roni on a stool, Alma on a stool, and Omri standing between them. It was two weeks after he came back, and it was the first time I allowed myself to believe that he was really here. It was the first time I felt that our home was whole again, that we were in our whole home, sharing an intimate moment—without a crowd around us and without all the chaos.”

On the wooden bench in the small garden, she sits back in jeans, sparkly nail polish and her hair tied in a bun at the nape of her neck. “It’s such a relief not to wear makeup,” she says. “When Omri was kidnapped, I went overnight from being a private person to a public figure. Public appearances demanded that I be presentable, composed, put-together and made up. Now, I don’t have to anymore.”

The front door opens and Omri steps outside, relaxed and smiling. No, he doesn’t know I interviewed his father, Dani, who just two weeks ago left Tel Aviv and returned to his home in Yesod HaMa’ala. And no, his father still hasn’t parted with the beard. “Maybe he feels that the long white beard has become his trademark,” Omri speculates.

He’s heading to a meeting, and she tells him, “Let me know you got there safely. Be careful in the rain.” What could be more ordinary than that? In some moments, they even feel as if none of it ever happened. But those moments are rare and fleeting. “October 7 isn’t some stain you can scrub away,” she says. “That’s why we need a state commission of inquiry. We deserve to know what really happened.”

What did you feel the first time you left the house and Omri stayed with both girls?

“It felt a little strange for all of us. We came back from Sourasky Medical Center on a Friday, and the next day, I went to a rally in Sha’ar HaNegev. That was my place from the beginning—I didn’t go to the Hostages Square in Tel Aviv very often. Roni and Alma looked at me like, ‘Where are you going?’ I answered their question and felt completely confident that Omri would manage just fine with them, especially since my mother was also there.”

Today at four, when the girls get back from preschool, their first question will be: Where’s Dad?

“I don’t know if Roni and Alma will be happy or disappointed that he’s not home—and I say that with a heavy heart. On one hand, I feel like they’re already confident that Dad is here. But even after two months, having him at home still doesn’t feel natural to them. I don’t see it yet in their eyes. It’ll take a little more time, but it will happen. I’m not worried.”

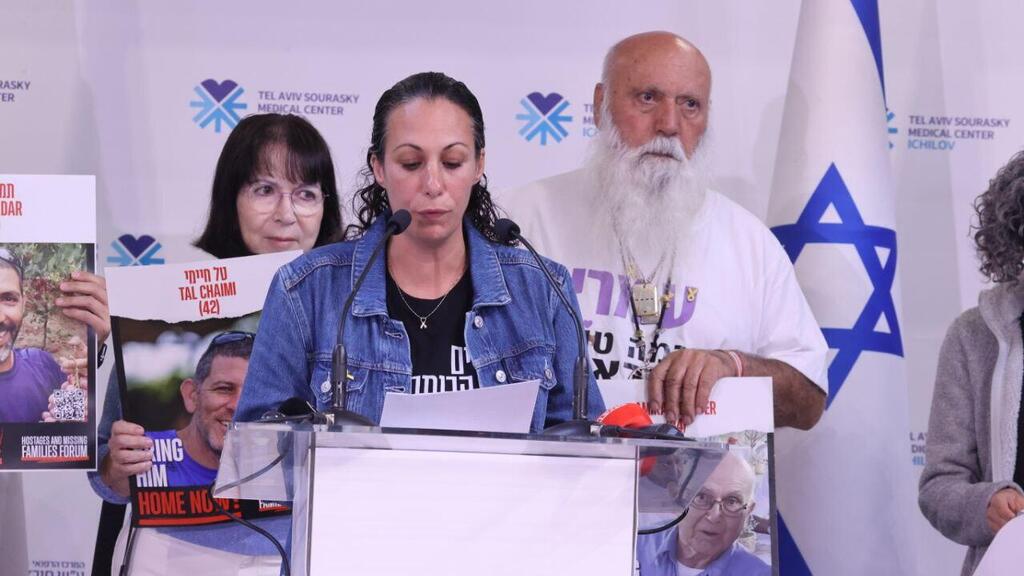

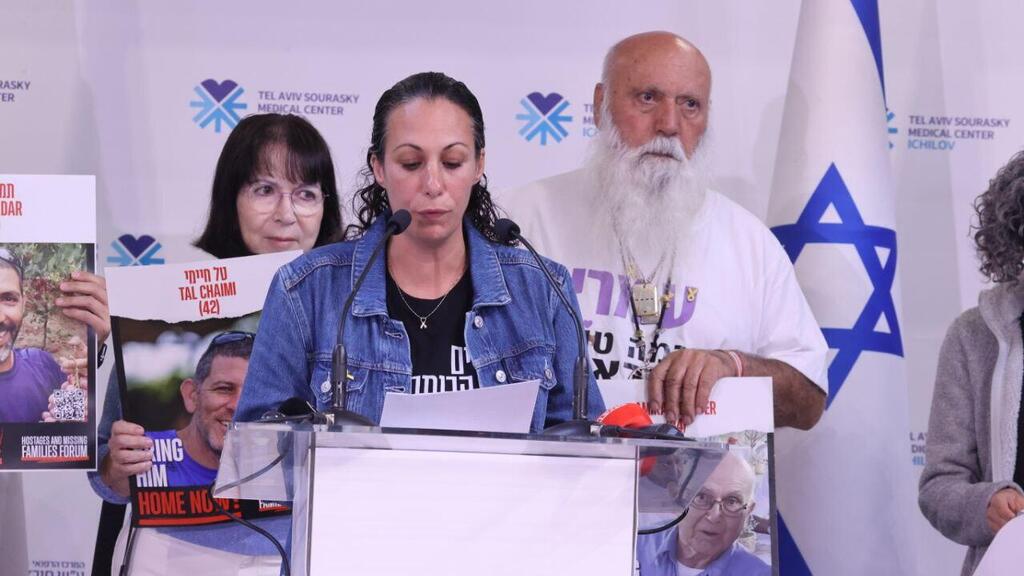

9 View gallery

Lishay Miran, with Dani Miran to her right, during a statement by families of hostage survivors at Sourasky Medical Center

(Photo: Moti Kimchi)

'On Oct. 6, we were thinking about three children. Since then, plans have changed'

Lishay, who turns 41 in January, was born in Sderot. “When I was 16, the Qassam rockets began, and I grew up between air raid sirens. At 25, when I was married to an Israeli who is half Belgian, we moved to Brussels for his medical studies. For five years, I taught Hebrew at a Jewish school and at the Sunday school for children of the Israeli Embassy, and I’d had my fill of city life. After the divorce, I moved back to Israel, to my parents’ home, and even Sderot felt too urban for me. There was no trace left of the small, warm town of my childhood. I rented a room at Kibbutz Mefalsim and spent 10 years working at Sapir College in a variety of roles.”

Omri, 48, grew up in Yesod HaMa’ala. “Over the years, he slowly made his way south. After a period in central Israel, in Ramat Gan, he came to Nahal Oz thanks to a friend, also Omri. They backpacked across India together after their army service, and my Omri arrived in Nahal Oz a month before Operation Protective Edge. Nahal Oz reminded him of his childhood in the moshava, and like many others, he fell in love and stayed.”

Are you planning to return to Nahal Oz?

“Yesterday, Omri and I were in Nahal Oz for the second time since he came back, and I told him I finally understood what’s been holding me back. It’s not that I’m afraid for my own safety—I just don’t know what kind of mother I would be there. Here in Kramim, the girls can leave the house, ride their bikes freely, and I’m calm. On October 6 two years ago, I was a calm mother in Nahal Oz. Today, I’m no longer sure I can be that person. Raising the girls in constant anxiety is not something I want.”

On Purim, they will mark six years together. Of those, Omri spent two years in captivity. “Our relationship had a few chapters. The first time we met, I was 30 and in the middle of a divorce. I had come back to Israel for a visit and hadn’t yet decided to return for good. Mutual friends told Omri, ‘Let it go, don’t get involved with her,’ because I was deep in the separation. Two or three years later, when Omri asked the same friends again, they told him, ‘Let it go, she’s not in the right place.’ The third time our paths crossed was on Purim, when I was 35.

“It’s not that we were against marriage. Omri was single, I was divorced, and as far as I was concerned, we were married in every sense. We held a ceremony that was ours—we created it, and a close friend officiated. We got married by the pool at Nahal Oz when Roni was a year old, and I was at the beginning of my pregnancy with Alma.”

9 View gallery

Lishay on stage at a rally calling for the release of the hostages

(Photo: Alex Kolomoisky)

At the kibbutz, Omri worked in landscaping, and in the afternoons returned to his formal profession as a shiatsu therapist, seeing patients at a clinic he called “Ehad Ha’am.” Lishay continued her academic career, commuting between the kibbutz and Sapir College, where she completed a master’s degree in human resources management and organizational development consulting.

Omri became a father at 44; Lishay at 36. Roni was always a daddy’s girl. “Omri worked at the kibbutz, picked her up from preschool and took her for rides on the tractor.” Alma, however, grew up from the age of six months with her father only in photos and videos. “I promised her that when Daddy came home, he would take both of them for a bike ride,” she says, pointing to the rusted bicycles in the yard that Roni insisted on bringing from their home in Nahal Oz.

“Omri is an incredible father. I couldn’t have asked for a better one for my daughters. On October 6, we were thinking about three children, and since then the plans have changed a bit. I don’t know what will or won’t be. We have two amazing girls, and in every moment with them I’m reminded of how much strength these two little beings gave me. Over those two years, I knew how much strength I was drawing from them, and now, looking back, I tell myself it’s unbelievable. Two strong, brave girls—they truly are a great light.”

'In those first days, I told myself: just don’t let my Omri become another Ron Arad'

The entire world saw and heard the abduction video in which Lishay is heard saying goodbye to Omri with the words, “I love you. Don’t be a hero.”

“And everyone asked me why I told him not to be a hero. It just came out of me because I knew that the first instinct of people like Omri is to get up and fight. The monsters dragged us out of the safe room and into our kitchen. After 45 minutes, they moved us to the Idan family’s home”—the home of Tsachi Idan, who was later murdered in Hamas captivity, and his wife, Gali— “and there we were held hostage for two and a half hours. ‘Don’t be a hero’ came from a place of saying, ‘Don’t do anything reckless.’ And Omri really didn’t.”

How long did you keep hearing Roni screaming “my daddy,” as we saw in the video?

“It came back to me in moments when I allowed myself to lower my defenses and walls. At first, I heard her every night, and over those two years, I heard it many times. Since Omri returned, my soul has been calmer, and I see and hear it less. We’ve entered a different state of mind.

“Roni and Alma got used to living within a certain framework—one mother and two daughters with Grandma and Grandpa—and suddenly Dad came back. Roni struggled to hug and kiss the father who had disappeared from her life for two years, even though I constantly reminded them that Dad wanted to come back to them, that bad people took him and wouldn’t let him leave. Now we’re building the future on the foundation of the familiar past.”

Lishay and the girls were evacuated from Nahal Oz that Black Saturday, arriving in Kramim shortly after midnight. “We had nothing but the clothes on our backs. The monsters wouldn’t let me go back into the house—I couldn’t even take pacifiers. Roni and I were barefoot, wearing short-sleeved shirts. The only things that left the house were a can of baby's formula and a bottle, and that was it. And now go build yourself a life.”

“They put us in a guest cabin. A social worker arrived, people from the kibbutz came to help, and someone even stayed with me that first night. Everyone told me, ‘Put the girls to bed and then we’ll sit and talk for a moment, try to understand what you went through today.’ I told them I couldn’t. I had to be with the girls and strip away what was left of that terrible day from them.

“No one understood what I meant. They looked at me in shock. So I took off Alma’s smelly onesie, washed her in the sink and dressed her in clean clothes from the kibbutz. Then I went into the huge bathtub in the cabin with Roni—she had never seen a bathtub that big. I sat with her in the water and sang to her, ‘I’m washing my hands, tra-la-la.’ I was so happy when she laughed. I told myself, ‘I don’t care what happens tomorrow, and I don’t even know what happened today, but at this moment they’re going to sleep with a smile, and that’s what matters.’”

The next day, her parents, Ruth and Avner Lavi, arrived from Sderot to Kramim. “During the first year, we all lived together in one of the kibbutz guest cabins. I joked that at 40, I’d moved back in with Mom and Dad, all of us sharing one room with two little girls.”

Her first real crisis after the abduction came when Alma marked her first birthday, in March 2024. “I started counting the days Omri hadn’t been with her and realized that number had already surpassed the days he had been present in her life. I couldn’t believe we’d reached that point. When we also passed Omri’s 47th birthday, I told myself, ‘OK, now we’re starting to measure this in years.’”

At first, did you hope for an immediate release?

“It took me time to grasp the scale. When I understood that there were 251 hostages, I said, ‘What’s the problem? Stop everything, bring the hostages back and then do whatever needs to be done.’ But then a month passed, then two, then three.

“In those first days I told myself, ‘Just don’t let my Omri become Ron Arad.’ Why? Because there’s only one Ron Arad. I couldn’t even bring myself to say his name, because I was afraid to look straight at the most frightening possibility. During those two years, there were attempts to arrange a meeting between me and Tami Arad. She agreed and wanted to, but I was afraid to sit across from a woman to whom this had happened.

“Then the November deal came and collapsed, and I told myself, ‘OK, fine, another month, another two months—how long can this drag on?’ I was terrified of reaching a point where even Roni would have spent more time without her father than with him, and we were very close to that line. In the end, he came back before we reached it.”

In the first nights without Omri, she kept replaying the moment they said goodbye. “But I didn’t live October 7 very much, I didn’t allow myself to. I was very tightly held together for Omri and for the girls. I told my therapist, a wonderful psychologist, ‘I’m holding on, I’m in holding mode.’ Looking back, I functioned like a machine.”

'I hoped he would manage to hold on until Omri came back, but old age and longing overcame him'

Now they are once again a family of a father, a mother and two daughters. “Every morning I give them three options to choose from—who will take them to preschool: me, Omri or both of us—so they get used to the idea that Mom isn’t the only option. I’ve been in psychological care for two years now, and Roni started therapy with dogs as early as October 11. Partly because at 2.5 there wasn’t really room for conversations with a psychologist, and partly because Roni really loves dogs.”

And this brings us to the reason for this interview. Precisely now, two months after Omri’s release from captivity, when she is making such an effort to return to anonymity and routine, Lishay has agreed to an open conversation because the children’s book she wrote is being launched at ANU – Museum of the Jewish People in Tel Aviv. The book is titled “Mojo’s Return: A Story of Resilience and Hope.”

In Nahal Oz, they had a dog named Mojo. “He was a mixed-breed dog, about six months old when Omri adopted him. Mojo was with us in the safe room, and when the monsters dragged us into the kitchen he started barking and irritated them, so they threw him out of the house. When we were rescued, I had a few minutes to look for Mojo, but I couldn’t find him.

“Ten days later, he was found in our home in Nahal Oz, under a pile of clothes, exhausted and terrified. He was taken to the veterinary hospital in Ben Shemen and afterward brought to us in Kramim, but by then Mojo could no longer walk. He had a herniated disc from before the war, and everything he went through took away his ability to stand on his legs.

“After a week, I returned him to the veterinary hospital because it was very hard to care for him. He couldn’t walk, dragged himself on his belly and got scraped and injured. But then, just when we had almost given up, someone from Kramim decided to foster him until Omri came back. The kibbutz member took incredible care of him, bought him a wheelchair so he could walk and get around. When we came to visit, Mojo wasn’t happy to see me. He went wild trying to look for Omri with me or next to me. But with Roni, he was very happy.”

Six months ago, at the age of 14, the decision was made to put him down. “I told one of our friends that Omri would never forgive me if I buried him outside Nahal Oz. That’s where, in the ‘Grandchildren’s Grove,’ all the kibbutz dogs are buried. That night, I drove there and we held a dignified funeral for Mojo. I so hoped he would manage to hold on a little longer, until Omri came back, but old age and longing overcame him. My older sister, Michal, who was evacuated from Or HaNer and has since returned home, filmed the ceremony for Omri, who still hasn’t had a chance to watch it.”

She loves to read yet never saw herself as a writer. “But I’ve always been someone who would do anything for children. This book was written from the perspective of two little girls who lived for two years in uncertainty. The book was born thanks to my brother, Moshe, who lives in New York and was a central figure in the support group that accompanied me and the campaign.

“At an advocacy rally he organized in New York, he met Mary Millman, who fell in love with our story. We touched her heart, and she looked for ways to help. One day she told Moshe, ‘Tell Lishay I want her to publish a children’s book, we’ll write it together.’ Mary brought in her friend Melissa Stoller, a children’s author in the United States, and we connected for long Zoom conversations that moved back and forth between Hebrew and English.”

At their very first Zoom meeting, the three of them agreed that the book’s hero would be Mojo. “Mary, who loves dogs, met Moshe shortly after Mojo was brought back to Nahal Oz, and that gave me tremendous hope. If Mojo came back, maybe Omri would come back too.

“Our story opens with a family of four—parents and two daughters—who on a sunlit Simchat Torah morning ate blueberry pancakes and played with Mojo in the shade of their old lemon tree, until everything changed. A wild storm swept in from the desert, and Mojo and Daddy were swallowed up in the chaos and the tempest, until one day Mojo returned home, limping. Mommy was overcome with emotion and said it was a miracle, and the girls were happy. Even with an injured leg, he was still their Mojo—but someone was still missing. Family, friends and strangers prayed for Daddy’s return.” The pastel illustrations by Uzi Binyamin help give the book its subtitle, “A Story of Resilience and Hope.”

The writing was completed more than a year ago, and when the book moved into production and printing thanks to philanthropists, among them the Museum of the Jewish People and the museum’s friends associations in Israel and the United States, Lishay made a principled decision. “The first person to read the story to Roni and Alma would be Omri, not me.” Only in recent months did she share with her daughters the secret of the book that was on its way. Last week, when the first copy arrived at Kibbutz Kramim and Omri was the first to read it to them, Alma said, “But our daddy came back.”

During the first year and a half after the abduction, she flew only to Hungary. “Omri has Hungarian citizenship. His mother, of blessed memory, was from Hungary, and I thought maybe that would help. I also focused on Europe because I couldn’t bear being so far from the girls.

“Only in the past six months did I realize I had to fly to the United States as well. The first time I went, in May, there was once again talk of a deal. When we arrived at the Israel Day Parade in New York, the negotiations collapsed. Two months later, I flew again to the U.S., with Keith and Aviva Siegel and with Liran Berman. At the time, the Israeli delegation was in Doha, and we all had the feeling that this was it, that it was about to end. In the morning, we woke up to headlines saying the Israeli delegation had returned from Doha. That, too, was a moment when the nightmare could have ended. And there were other moments like that, before and after.”

How did you survive life suspended between hope and disappointment?

“Whenever I was asked, ‘What, don’t you want all the hostages to come back at once?’ I answered, ‘No, I want something to finally begin,’ because I would never say no to saving lives. That’s what guided me the entire time, because I knew Omri would be among the last.

“That was true both because of his relatively young age, he isn’t even 50 yet, and because there was no urgent reason to release him. We didn’t know his medical condition, but we had no evidence that he was wounded on October 7. And because the State of Israel did not give fathers any priority. When the hostages were divided into categories, there wasn’t even a category for fathers. Both at the time and in hindsight, I ask myself how that happened, after they declared, ‘Families will not be separated.’ How is it that to this day it’s still not clear that a mother and a father are the same?”

The pain that burns in her throat as she condemns the missed deals gives way to pointed indifference when she speaks of Israel’s prime minister, who still has not found the time to pick up the phone and call Omri to say hello and welcome home.

Do you feel Netanyahu delayed the deal?

“That I’ll answer only off the record. Over these two years, I pulled and absorbed a lot of fire. I was attacked over things I said about Bibi and Smotrich. I was among those who shut the country down for a day. It’s possible that the fire will be directed at me again in the future. But at this point in time, I want to ease off the gas a bit. That also comes from a desire to return to anonymity, as much as possible. I’m not disappearing and I won’t disappear. I know my voice matters, and it will continue to be heard.

“Clearly, a lot of political considerations were involved in the negotiations. That’s why a state commission of inquiry must be established. The families of the fallen, the hostages, the victims of the Nova festival, the communities around Gaza and the entire Israeli public deserve to know and understand what really happened on October 7. My criticism of the prime minister is well known. This could have ended earlier, much earlier.”

Did you have direct contact with the prime minister?

“He called only once, under terrible circumstances. Netanyahu had just finished a visit to Hungary, and before boarding his flight he spoke about ‘the Hungarian hostage.’ That set me off, because ‘the Hungarian hostage’ is Omri—he has a name, and first and foremost he is Israeli. I posted on X that the Hungarian hostage’s name is Omri, and 10 minutes later Netanyahu called. He said I was right, that he should have mentioned him by name, and that he had indeed been talking about Omri in the conversations he held. Today, I’m no longer waiting for a call from him—certainly not for a meeting.”

And did you have any contact with Sara, the child psychologist?

“None. Zero. I met her once, right at the beginning, when they started holding meetings with all the hostage families at the Kirya. At one of those meetings, the two of us were sitting around the same table. Maybe she didn’t identify me as the mother of two girls whose father had been kidnapped. Maybe she didn’t look at me at all. I was just one person in a large group.

“Three weeks ago, Omri and I flew to the United States to say thank you to Trump, and I couldn’t avoid making comparisons. The president of the United States has time to meet with families of hostages. Even though I was among those who spoke with him only by phone, he made me feel that this is how the world is supposed to work. I met with Steve Witkoff more times than I ever met with Ron Dermer, who was in charge of the negotiations. I met with Gallant several times and lashed out at him forcefully, I didn’t spare anyone my criticism. Not Ronen Bar either, or Nitzan Alon, who wasn’t connected to the failure in any way because he wasn’t in the army at the time. It was hard, but at least there was dialogue, not total disregard.”

And if, at this very moment, you saw Netanyahu approaching your home, what would you say to him?

“I have nothing to talk to him about. The only thing I need to say is that a state commission of inquiry must be established. I would tell him that the time has come for him to step down, to release us from his grip, because we are effectively captives in his hands, subject to his will. How is it possible that to this very day Bibi has not invited the last 20 Israeli heroes who returned alive from captivity, or the 27 families of the hostages who were brought back in coffins? Not that I’m waiting for an invitation. I was never the point. All along I said, ‘Lishay is not the story — they are.’ If it hasn’t happened by now, it probably never will.”

'Omri doesn’t talk much about Gaza, but the memories surface on their own'

The support group that stood by her for 738 days was her immediate family. “A lot of people say the war put their lives on hold, but my parents are the only ones who did that completely. They were with me in the cramped guest cabin until we moved to two adjacent mobile homes. Every time I was seen outside, abroad, someone stayed home with my little daughters. The evacuees from Sderot have long since returned to their homes, but my parents are still here. Today, it’s clear even to them that we’ll stay here until the end of the current school year, and that they will continue to be our anchor at the most basic level.”

Longstanding and new friendships also helped her endure. “In moments like these, you discover who your true friends are. It’s awful to say, but not everyone can go through something this terrible with you. Many of the families of other hostages became my family. I felt that only they could understand me without my having to say a word. That’s still true today. I imagine it’s similar to the bond Omri has with those who were with him there, even though for part of the time he was alone.”

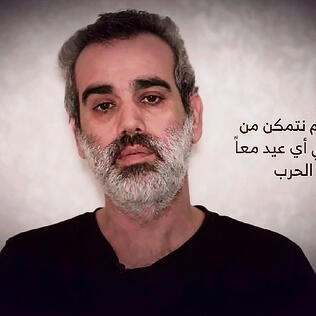

Meanwhile, Omri has chosen not to speak.

“It wasn’t a decision—he’s just not there yet. In the previous deal, in January, there was a sense of urgency in the air. The hostages who returned wanted to share their stories in order to create pressure to bring back those still in Gaza. Now too, when all the living hostages have returned, within days they were everywhere. But that doesn’t suit everyone.”

Neither of them has returned to work yet. “We’re working on becoming a family again. There’s no uniform protocol for recovery and returning to life. Everyone has their own wounds and injuries, even when they aren’t visible on the outside and are eating away at them from within. That’s why our friends announced a crowdfunding campaign, which in my view isn’t fundraising but a rehabilitation package that allows hostages and their families to get through the initial period. We have to take care of ourselves now, give ourselves a moment—not out of privilege and not out of indulgence. I’ve already heard that criticism too.”

You? Spoiled?

“They told everyone, ‘You’re back? Then go back to work, life goes on.’ I don’t understand what that means. Am I supposed to go back now to October 6? Beyond the fact that I don’t want to, I truly can’t do that. I wish I could erase these two-plus years. Omri misses doing shiatsu. He already has a new mat, but he still isn’t capable of giving treatments. He needs to rebuild his muscle mass and stamina. Over the past week, he’s treated me a little, just lightly. Before the war, I worked in management, and most of my job was in front of a computer, sometimes 12 hours a day. Today, I can’t concentrate. It may be that the ability is still there, but I need to rebuild it.”

Does the state provide support?

“It does. There’s a monthly stipend that comes in. Throughout the two years of captivity, I received money, some of it I set aside, but most went toward daily living and the struggle itself. But 9,000 shekels a month isn’t enough to rebuild a life. If October 7 hadn’t happened, we would already be living in Nahal Oz, in the home we finished building. Now we don’t have a home, and who knows when we will. Our crowdfunding campaign will allow Omri to breathe and plan for tomorrow without constant pressure.”

How does Omri sleep at night?

“It’s improving, but he still hasn’t returned to the good, healthy sleep he used to have. Omri doesn’t talk much about Gaza, but the memories surface on their own. When they talked on television about psychological terror, Omri said that for the first six months he had no idea what had happened to us. He didn’t know whether he still had a wife and two daughters. He talks about constant mortal danger — there were always armed people around him, and it didn’t take much for someone in a bad mood to put a bullet in his head.”

When Trump announced the release date, she moved up her flight from the United States. “I told the girls there had been good meetings and that Daddy would be coming home soon, and I packed suitcases with them with clothes for a family stay at the hospital. Later, I was told that Omri would be released in the first group that day. I left the house at six in the morning; my liaison officer came to pick me up. My mother stayed at my place with the girls. I told my mom, ‘Only after I see Omri will I let you know if there’s any point in bringing them,’ because I had no idea what condition he would be in. When the hostages were transferred from the Red Cross to the IDF, Omri was the first to step out of the van. When I saw the way he moved, and the small, crooked smile at the corner of his mouth, I called my mom, and she set out with them on the way.”

What did you miss most during those two years?

“The blue check marks on WhatsApp. For two years I sent him messages. I opened a group for just the two of us — ‘Notes for Omri-li’ — and I wrote to him endlessly. Sometimes it was, ‘Alma is walking,’ or ‘Roni is riding her bike on her own,’ and sometimes it was, ‘I’m having a hard time, man, just come back already.’ Thousands of messages were saved on my phone, and not one of them got a response. Omri has already finished reading all of them.”