In the early hours of Sept. 22, 1979, a U.S. military satellite orbiting thousands of kilometers above the Earth recorded an unusual and startling event over one of the most remote regions on the planet. Over the southern Indian Ocean, near the desolate waters surrounding the Prince Edward Islands, the satellite detected a brief but intense burst of light. Within milliseconds, a second, longer-lasting glow followed, producing a pattern that immediately drew attention inside U.S. military and intelligence circles.

To the engineers and analysts monitoring the Vela satellite system, the signal was not merely curious — it was deeply alarming. The satellites had been designed for one specific mission: to detect secret nuclear explosions conducted in violation of international treaties. Since their deployment, every confirmed instance in which the system had recorded this distinctive “double flash” pattern had later been conclusively linked to a nuclear detonation. The phenomenon was considered so reliable that it formed a cornerstone of U.S. confidence in global nuclear monitoring.

This time, however, there would be no official confirmation.

More than four decades later, the so-called “Vela incident” remains one of the most controversial and politically sensitive episodes in the history of nuclear intelligence. The United States has never formally acknowledged that a nuclear explosion took place. Israel has never commented publicly on the event. South Africa has consistently denied responsibility. Yet among nuclear physicists, intelligence analysts, historians of proliferation, and former policymakers, a broad — if unofficial — consensus has emerged over time: the flash was almost certainly man-made, and Israel is widely regarded as the most plausible source.

The incident cannot be understood in isolation. It sits at the intersection of Cold War geopolitics, U.S. nonproliferation policy, regional power dynamics, and Israel’s long-standing strategy of nuclear opacity — a doctrine shaped by secrecy, strategic calculation, and the existential fears born from Jewish history in the 20th century.

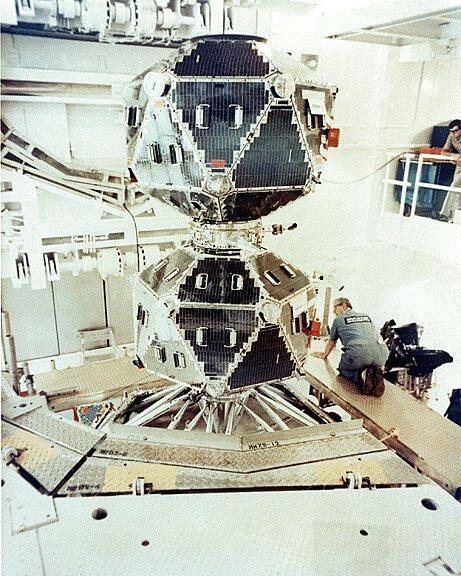

A satellite system designed to catch cheaters

The Vela satellite program was a direct outgrowth of the 1963 Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, which prohibited nuclear explosions in the atmosphere, outer space, and underwater. The treaty represented an early attempt by nuclear powers to limit the environmental and geopolitical consequences of atomic testing, but its success depended on the ability to detect violations anywhere on Earth.

To enforce compliance, the United States developed and deployed a constellation of satellites equipped with highly specialized optical sensors known as bhangmeters. These instruments were designed to detect the precise optical signature of a nuclear explosion — a rapid, intense flash of light followed almost immediately by a second, slower pulse caused by the interaction of the fireball with the surrounding atmosphere.

By 1979, the Vela system had already detected dozens of nuclear tests conducted by the United States, the Soviet Union, China, and other nuclear-armed states. Crucially, none of the detections had later been proven false. Within the intelligence community, the system was regarded as exceptionally reliable, even conservative in its reporting.

The satellite that recorded the Sept. 22 event — Vela 6911 — was nearing the end of its expected operational lifespan, but its sensors were still functioning within acceptable parameters. Subsequent technical analysis suggested the signal was consistent with a low-yield nuclear explosion, likely in the range of two to three kilotons. While far smaller than the bomb dropped on Hiroshima, such a yield would have been more than sufficient to validate a weapon design, test a triggering mechanism, or confirm the performance of a compact or “clean” nuclear device.

The estimated location of the event, far from shipping lanes and population centers, appeared almost tailor-made for a clandestine test.

The scramble for corroboration

Within hours of the detection, U.S. intelligence agencies initiated a broad, multi-layered response aimed at confirming or refuting the satellite’s reading. Aircraft were dispatched to collect atmospheric samples in the southern hemisphere, searching for radioactive debris that could confirm a nuclear detonation. Underwater hydroacoustic monitoring systems, originally designed to detect submarine activity and nuclear tests, were reviewed for anomalous signals.

Meteorological data was analyzed to determine potential fallout trajectories. While no definitive radioactive cloud was detected, traces of iodine-131 — a short-lived byproduct of nuclear fission — were later identified in sheep grazing in parts of Australia. Although not conclusive on their own, these findings were considered by some scientists to be consistent with a distant nuclear explosion.

Additional anomalies surfaced elsewhere. The Arecibo radio telescope in Puerto Rico detected an unusual ionospheric disturbance moving in a direction consistent with the suspected blast location. Naval listening systems reportedly registered acoustic signals that some analysts later characterized as compatible with a near-surface or shallow underwater explosion.

Privately, early intelligence assessments reportedly described the evidence as pointing with “high confidence” to a nuclear test.

Publicly, however, the U.S. government hesitated.

A political crisis for Washington

For President Jimmy Carter, the implications of the Vela detection could scarcely have been more destabilizing. Carter had made nuclear nonproliferation one of the central pillars of his foreign policy, frequently framing it as a moral obligation as well as a strategic necessity. Earlier that same year, he had brokered the Camp David Accords between Israel and Egypt, a diplomatic achievement that reshaped the Middle East and consumed enormous political capital.

A confirmed Israeli nuclear test would have triggered mandatory sanctions under U.S. law, potentially including the suspension of military assistance. It would have strained relations with a key regional ally and severely complicated Washington’s ability to press other countries — particularly adversaries — to adhere to nonproliferation norms.

According to later accounts by former officials and historians, senior figures inside the administration feared that acknowledging the test would force the United States into an impossible position: either confront Israel publicly and risk destabilizing the Middle East, or quietly abandon the credibility of its own nonproliferation commitments.

The administration chose ambiguity.

The Ruina Panel and the management of doubt

To manage the growing internal controversy, Carter convened an independent scientific review panel chaired by MIT physicist Jack Ruina. The panel was tasked with examining the Vela data and assessing whether alternative explanations could account for the observed signal.

The panel ultimately concluded that the event was “probably not” a nuclear explosion, suggesting instead the possibility of a sensor malfunction or a rare natural phenomenon, such as a meteoroid strike or an unusual atmospheric interaction. Critics later noted that these explanations were speculative and lacked empirical support.

Importantly, the panel focused narrowly on the satellite’s optical data and did not fully incorporate classified intelligence, hydroacoustic readings, or contextual information regarding Israeli or South African military activity in the region at the time.

The report provided political cover. Carter publicly downgraded the administration’s assessment to “inconclusive,” allowing the issue to fade from public scrutiny without forcing a confrontation.

The debate did not end. It was merely buried.

Israel and the bomb: the origins of a secret program

By the time of the Vela incident, Israel’s nuclear status was already one of the world’s most carefully guarded open secrets. Israel has never signed the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty and maintains a policy of deliberate ambiguity, neither confirming nor denying possession of nuclear weapons while stating it will not be the first country to “introduce” them to the Middle East.

Western governments, including successive U.S. administrations, have largely respected this posture.

The roots of Israel’s nuclear program lie in the trauma of the Holocaust and the existential insecurity of the country’s early years. David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first prime minister, was deeply convinced that the Jewish state could never again rely solely on external guarantees for its survival.

“What Einstein, Oppenheimer and Teller made for the United States,” Ben-Gurion famously said, “could also be done by scientists in Israel.”

Even as the 1948 war of independence raged, Israel began recruiting Jewish scientists from abroad and laying the institutional foundations of nuclear research. In 1949, an IDF scientific unit known as Hemed Gimmel began surveying the Negev desert for uranium deposits, while Israeli students were sent overseas to study nuclear physics under leading figures such as Enrico Fermi.

In 1952, the effort was formalized under the Ministry of Defense. Ernst David Bergmann, a German-born chemist and close adviser to Ben-Gurion, emerged as the program’s intellectual architect. Bergmann rejected the notion that nuclear energy could be neatly divided into civilian and military applications, famously stating that no such distinction truly existed.

French cooperation and the creation of Dimona

The decisive breakthrough came through France. In the mid-1950s, France was Israel’s principal arms supplier and strategic partner. Following the Suez Crisis, Paris agreed to assist Israel in building a nuclear reactor and reprocessing facility near Dimona in the Negev desert.

Officially, the reactor was presented as a civilian research installation. In practice, it was designed to produce plutonium suitable for nuclear weapons. French engineers played a central role in construction, and Israeli scientists reportedly enjoyed unprecedented access to French nuclear facilities and test data. Heavy water and uranium were supplied covertly through complex international arrangements.

By the early 1960s, U.S. intelligence flights detected suspicious activity at Dimona. Israel initially claimed the site was a textile factory, a story that quickly collapsed under scrutiny. President John F. Kennedy demanded inspections, leading to a series of tightly controlled, pre-announced visits by U.S. scientists.

According to later accounts, these inspections were carefully staged to conceal the facility’s true purpose. After Kennedy’s assassination, pressure eased. By 1969, under President Richard Nixon, inspections ceased entirely.

That year, Nixon and Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir reached a secret understanding: Israel would not test or publicly declare nuclear weapons, and the United States would not press the issue.

Nuclear opacity became institutionalized policy.

Crossing the nuclear threshold and the shadow of Vela

By late 1966 or early 1967, U.S. intelligence believed Israel had completed its first deliverable nuclear weapon. On the eve of the Six-Day War, Israeli scientists were reportedly ordered to assemble crude devices in case the state faced imminent defeat — a contingency later referred to as the Samson Option.

Israel won the war decisively, and the weapons were never used. During the Yom Kippur War in 1973, however, Israel reportedly placed nuclear-capable aircraft and missiles on alert as Arab forces made early gains. Some analysts believe the implicit nuclear threat helped spur rapid U.S. resupply.

By 1979, Israel’s nuclear capability was widely assumed among intelligence professionals. What remained uncertain was whether it had ever been tested.

The Vela flash may have answered that question.

Vanunu, reassessment, and the long silence

In 1986, Mordechai Vanunu, a former technician at Dimona, shattered decades of silence by providing photographs and testimony to the British press. His disclosures suggested Israel had produced enough plutonium for dozens — possibly hundreds — of weapons and had developed boosted and potentially thermonuclear designs.

Vanunu was abducted by Mossad agents, returned to Israel, and imprisoned for 18 years. His revelations, however, reshaped how earlier events — including the Vela incident — were understood.

Investigative journalist Seymour Hersh reported that senior U.S. officials privately believed Israel had conducted the test, possibly with South African logistical support. Israeli nuclear historian Avner Cohen later wrote that a “scientific and historical consensus” had emerged that the Vela event was a nuclear test and “had to be Israeli.”

South Africa, which dismantled its nuclear arsenal in the 1990s, acknowledged building six bombs but denied possessing the capability to test advanced devices in 1979 — strengthening suspicions that Israel supplied the device.

In 2010, Carter’s White House diary revealed that by early 1980 there was “growing belief among our scientists” that Israel had conducted a nuclear test near southern Africa. It was the closest any U.S. president came to acknowledgment.

Why the flash still matters

The Vela incident is no longer primarily a technical mystery. It is a political one.

The double flash over the southern ocean illuminated not only a possible nuclear detonation, but the architecture of silence that governs nuclear weapons when allies are involved. For Israel, it remains an unspoken chapter in a nuclear history that officially does not exist. For the United States, it marks a moment when scientific evidence yielded to geopolitical necessity.

And for the world, it serves as a reminder that nuclear secrets leave traces — even when no one dares to name them.

First published: 17:35, 01.29.26