On the evening of October 7, Col. (res.) S. was hosting his extended family at his home in a kibbutz near the Gaza border. As a reserve officer holding a key position at the operational heart of the Israeli air force at the Kirya military headquarters in Tel Aviv, he keeps a packed bag ready at all times.

“As soon as the red alert warnings started, then the explosions and sirens, we all went into the safe room with the children and our partners,” he recalled. “About 15 minutes later, the terrorists began reaching the kibbutz fence. And I, like an idiot, walked out of the safe room, put on my uniform and drove to the Kirya. At the same time, my son left the safe room too — but to organize his weapons and fight for the kibbutz.”

S.’s son, a major in the elite Maglan unit, became one of the war’s heroes. S.’s wife, an operations officer in the local emergency squad, also left the safe room to coordinate the team and inform them that their son was joining the fight. For seven uninterrupted hours, the younger S. fought dozens of heavily armed terrorists, some equipped with RPG launchers and heavy weapons. Together with the emergency squad, he helped prevent the terrorists from overrunning the kibbutz.

“And what did I do?” his father said. “With total lack of awareness, I got into my car and drove north, under gunfire, columns of fire and smoke, wounded people along the roadside. All I could think about was how to activate, and quickly, Operation Sword of Damocles.”

The emergency order, considered among the most classified in the Southern Command and the air force, was designed for immediate strikes on sensitive Hamas assets across Gaza, including command centers and major attack tunnels, such as the massive tunnel opposite Netiv HaAsara, a short run from S.’s home.

In retrospect, Air Force officials acknowledge that Sword of Damocles was ineffective and irrelevant. Hamas’ “Jericho Wall” plan was already underway, with thousands of gunmen infiltrating Israel and carrying out massacres in communities, army bases and outposts.

Around 9 a.m., after a rapid drive north along Highway 4 amid sirens and ambulances, Col. S. disappeared into the depths of the air force command bunker, leaving behind his son fighting and his family trapped in the safe room. He left his phone behind and ran downstairs to what would become the defining project of his career: Nahalat Binyamin.

Fatal date

The project is a comprehensive system responsible for planning high-value air force targets across all theaters, near and far. “This huge machine was already operating and filling up,” S. recalled. “More and more people arrived from home and took up positions.”

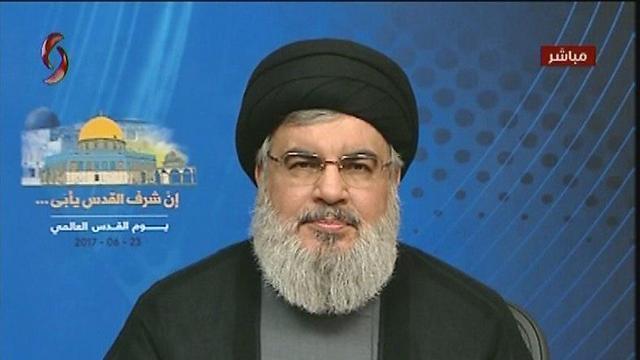

Deep underground, the air force’s target bank matches bombs with Hamas operatives, missile launchers in Iran and even Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah himself. These precise, lethal “dates” are planned by intelligence and targeting officers working across dozens of screens.

The project began 13 years ago and reached its peak during the war. Today, it includes more than 100 people, mostly young officers, using advanced technologies such as 3D target visualization, regardless of location. “Some targets are planned in minutes. Others take years, like Nasrallah’s bunker in Dahiyeh,” S. said.

Every target is examined in depth: potential collateral damage, likelihood of success, the precise angle and type of munition needed to strike a target 50 meters underground beneath a residential building. “It’s not enough to drop 83 bombs,” S. said. “We calculate time gaps of half a second or 2.2 seconds between bombs. Every tenth of a second, every few degrees, can mean success or failure.”

The team models scenarios in which intelligence certainty drops from 100% to 87%, or the target is in a different room, floor or depth. “How many people would be killed by such a deviation after a JDAM detonates — all of this goes up the chain for senior approval,” he said.

Enemy air defenses are also factored in. Until 2024, Hezbollah operated an advanced air defense network of more than 100 Iranian and Russian systems, which the air force systematically dismantled ahead of Operation Northern Arrows.

One and a half tons of explosives

Although its foundations predated the war, Nahalat Binyamin was fully activated on October 7 and became operationally embedded throughout the fighting. Teenagers and young adults analyze each strike with surgical precision, even when Israeli ground forces are just 80 meters from the target.

“The air force pushed close air support to an extreme no other military has dared,” said one officer. “We learned how to drop 1.5 tons of explosives while infantry and armored forces were just hundreds of meters away, calculating not only where soldiers were positioned but the angle at which a bomb would hit a building or tunnel.”

One of the project’s most intense challenges came on July 13, 2024, when intelligence pinpointed Hamas military chief Mohammed Deif. “It was zero to 100,” S. said. “Four hours passed from the moment the mission was received until two small bombs struck Deif’s compound in western Khan Younis.”

Throughout those hours, planners weighed structural collapse rates, civilian casualties in the displaced persons compound where Deif was hiding and the presence of senior operatives. All of it unfolded under mounting international criticism of civilian casualties in Gaza.

S. said the air force’s collateral damage thresholds were revised more than 100 times during the war, depending on conditions and objectives. “The policy of July 2024 was not the policy of October 2023,” he said.

The air force also made mistakes: munitions that failed to detonate, missed targets and hostages killed in airstrikes.

“There is a heavy burden when you pay a high price without results,” S. said. “The hardest moments were when hostages were killed by our strikes, no matter how it was later phrased. That was our greatest nightmare.”

He said every such incident was rigorously investigated and lessons were immediately implemented. “We work with dedicated military engineers who tell us the probability a structure will collapse. We adjust the explosive weight accordingly. We try to minimize harm to civilians, but even the wife of a Hamas operative sleeping beside him is factored into collateral damage calculations.”

S. said the unit’s evolution led to unprecedented capabilities. “At the start of the war, I doubt we could have struck a room next to an active maternity ward or emergency room. This year, when we killed Mohammed Sinwar, that’s exactly what we did — without damaging the ER next door.”

He added, “Today we understand far better what every bomb does, down to its effect on blocking a tunnel junction. That knowledge has changed everything.”

There are also legal advisers

One of the senior planners in Project Nahalat Binyamin is Maj. R. “I also pass upward recommendations and professional opinions,” he said. “For example, if I assess that for a given target value, there is a high likelihood that more than 10 civilians will be killed. The chief of staff instructed us to prepare in advance and retain a file for every strike, including the calculations we made. And of course, there are sensitive strikes that require approval by the air force commander, the regional commander or the chief of staff.”

Within Nahalat Binyamin, as in the command and divisional operations rooms, there is a permanent presence of legal advisers.

The most complex days for him came during Operation Rising Lion, the short campaign against Iran in June. As hundreds of air force aircraft operated thousands of kilometers from Israel, he was required to manage erupting operations, pilot risks and surprise scenarios across multiple arenas simultaneously.

“For the first time, we were operating the air force at full capacity,” he said. “We managed priorities. I could change the air picture in a single second if a new target suddenly appeared on one side of vast Iran while an aircraft formation engaged on another mission was on the opposite side.

“As planned as Rising Lion was, there were flights whose missions I changed three times while they were already in the air, and the missions kept popping up. You’d have fighter jets on their way to strike missile launchers aimed at Israel, and suddenly new intelligence would come in on the location of a senior and critical Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps figure who had to be eliminated. What do you do? Divert the aircraft or launch a new sortie from faraway Israel? These were the dilemmas we dealt with every day. It’s choosing between a target planned over 10 years and a target in Iran planned in five minutes.”

The Iranians likely understood well the value of the air force command bunker. At the height of Operation Rising Lion, those inside the unit’s main war room clearly felt the Iranian missile that was aimed at the Kirya in Tel Aviv but struck a residential tower on Kaplan Street. The blast shook the air force’s command building, shattered some lobby windows and, according to accounts, dust penetrated underground.

“Hundreds of phones stored in lockers on the ground floor were knocked down by the shockwave, some smashed on the floor,” air force personnel said. But the work never stopped. “We had drilled for such a scenario, even though there was no direct hit where we were,” Col. (res.) S. said. “It was an extremely crowded night in the bunker. People simply didn’t go upstairs and kept sleeping on mattresses in my office between shifts.”

Maj. R. said everyone felt and understood what had happened. “You have to remember that aside from aircrew, we don’t have fighters trained to operate under fire. So we went station to station to calm the young soldiers. I explained what had happened and told them we were continuing at full pace. I personally did go upstairs between shifts, mainly to fly sorties as a pilot in my parent squadron, Squadron 100.”

From the bunker to the delivery room and back

Working alongside Maj. R. during those days was Lt. T., a mission officer who did everything, in every arena, from Yemen to Beirut. At any given moment, up to 10 planning teams operated under her, preparing 20 different targets slated for strikes within the next three hours.

“And I have to do all of this while also taking care of our reservists, dealing with the here and now and with what’s planned for two days from now, because an operation like this runs on an organized weekly plan,” she said.

Her commander, Col. (res.) S., said he was proud of his team’s motivation. “We had pregnant officers here who worked literally until the last moment, including one who walked out of the operations room straight to the delivery ward at Ichilov Hospital, and two weeks later returned from maternity leave to take shifts because we were in the middle of a war and no one cared that she was breastfeeding in the operations room. These are the most capable and intelligent women and men you can imagine, people who could easily have excelled in medical school or landed a coveted job at Microsoft, but chose to be here underground, planning a rescue strike for a Nahal Brigade force in Rafah.”

There is one strike — perhaps the one that contributed to the end of the war — that S. and his team speak about sparingly: the major and controversial opportunity to eliminate Hamas’ leadership in Doha, ordered by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu against the recommendations of senior defense officials. The directive reached S. and his team, who were tasked with translating it into an airstrike. It failed, and its results triggered a global storm felt from Doha to Washington.

In careful wording, S. suggested the problem lay in partial intelligence on which the decision to proceed was based. “There is a technical side and a managerial side to these strikes,” he said. “I know how to bring the bomb into the room.”

S. also described another failed strike from which Nahalat Binyamin drew lessons. Ali Karki was commander of Hezbollah’s southern front, a senior and veteran figure in the organization. In September 2024, the mission was approved to kill him in a low-rise building where he was hiding in southern Lebanon, but the munition was apparently too small.

“He was only hit by shrapnel in the leg,” S. said. “Within days, he had already been discharged from the hospital straight to Nasrallah’s bunker in Beirut, where he was killed together with him.”