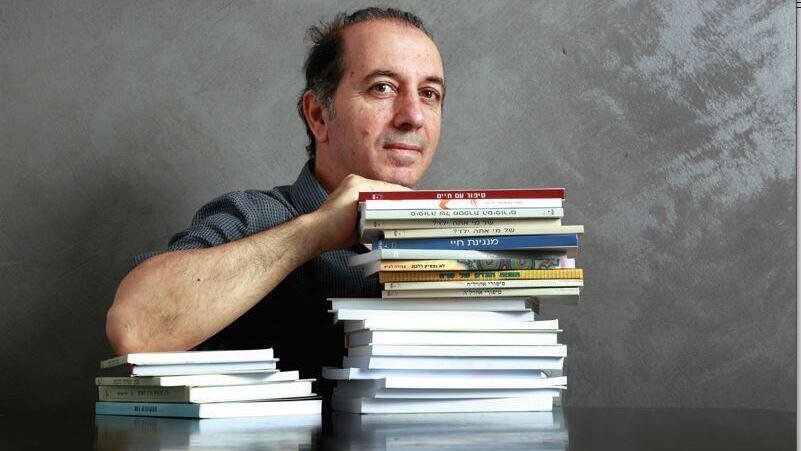

“You think there is a bottom to what they endured, and then you discover it goes even deeper,” so says Eli Halifa, the ghostwriter behind the stories of some of Israel’s most searing trauma survivors, including two hostages returned from Hamas captivity. Caught between a midnight call from ex-hostage Eliya Cohen remembering a detail from his time in captivity and the look on Rivka Bohbot’s face as she listened to her husband Elkana Bohbot speak for the first time, Halifa navigates a role that demands emotional precision and almost impossible sensitivity.

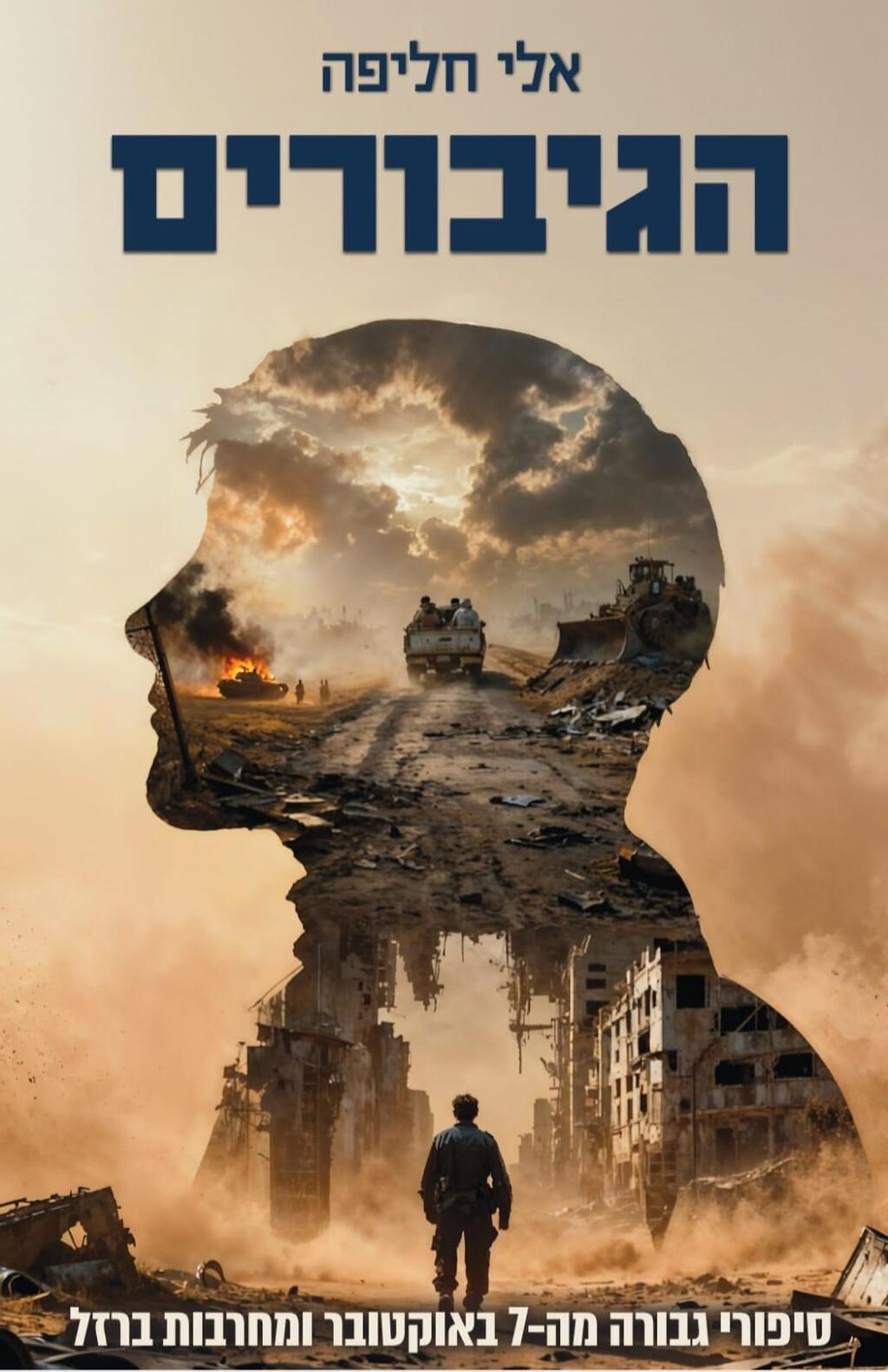

As a ghostwriter, he pieces together the mosaic of courage displayed by Israelis who chose lives of meaning long before October 7. In his new book “Giborim” (“Heroes”), he presents 30 unsettling and powerful stories. In an interview, he describes the emotional cost of carrying others’ pain — and the moment the testimonies became too heavy even for him. “I realized I had a problem,” he says. “It was getting to me too much.”

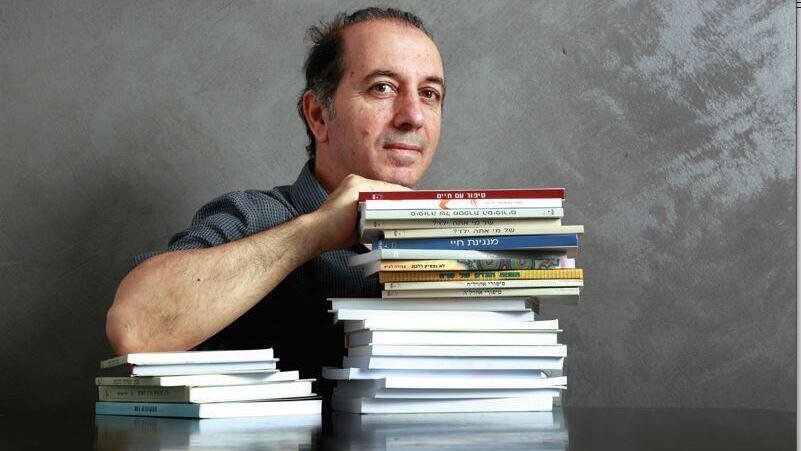

5 View gallery

Eli Halifa, the ghostwriter behind the stories of some of Israel’s most searing trauma survivors

One of the book’s opening monologues belongs to Armored Corps officer Eden Provisor, who fell in Gaza. In his final phone call home, he told his father, “Dad, we’re in hell here, and the situation is bad. I can’t tell you what will happen, but there’s a chance I won’t come home. I need you to keep living as if I’m there with you. Don’t fall apart. Enjoy life. Do what we loved to do. I’m serious.”

The book gathers the stories of 30 Israelis thrust into unimaginable situations on October 7. Halifa stresses that while the book will serve as testimony for future generations, he rejects the idea that heroism is synonymous with sacrifice. “We don’t sanctify death,” he says. “A person is born to live, not to die. I want us to know how they lived, not only how they died.”

Meaning that the final moments of those killed are only one expression of their heroism.

“Yes,” he says. “I wrote in the introduction: ‘Heroism is not created in a moment and does not emerge from nothing. It may appear suddenly in full force, but in truth it is the product of entire lives — shaped since childhood by leadership, responsibility and values.’”

'These aren’t people who suddenly became heroes; this is how they lived'

The inspiration for the book came after Halifa, who also ghostwrites the life stories of returned hostages, was approached by the brother of Chief Warrant Officer Uri Moyal, murdered in a terror stabbing at a café in March 2024. “His brother had already written a book and wanted help preparing it for print,” Halifa recalls. “It was a 100-page eulogy that never ended, almost unreadable. I told him I’d edit it. But where was the man’s story? The mischief, the humor, the beauty? In the end, he died, yes, but where was his life? We can’t kill him again.”

Sixty-year-old Halifa took the idea to a publisher: a book compiling the stories of people whose lives, long before Oct. 7, had set the stage for their extraordinary acts. He visited 30 families and interviewed each of them.

Among the stories:

• Aner Shapira, a Nahal soldier who stood at the entrance of a roadside bomb shelter on October 7 and repeatedly threw terrorists' grenades back outside to save those holed up inside with him.

• Amit Mann, a medic who remained in Kibbutz Be’eri’s unfortified dental clinic to treat gunshot injuries during the Hamas-led attack.

The country, Halifa notes, has long been shaped by a mythology of sacrifice — from language to education to memorial culture — where heroism is framed almost exclusively through death. He wants to redirect the focus to life. “The goal is to tell their stories,” he says, “but not only the story of how they died. It’s about how they lived as heroes. That’s where you learn their spirit.”

He tells the story of Amit Mann, the medic from Be’eri. She was initially rejected by the army because of a muscle condition, fought her way into the medical track and spent her life saving others. “Yes, she was murdered,” Halifa says, “but her heroism was in how she lived. These aren’t people who suddenly became heroes — this is who they were.”

'You can raise children who care'

So is heroism something that can be taught?

“Of course. You look at how parents raised them and you understand the values they instilled in them. You can raise children and citizens who care.”

He describes families whose loved ones acted instinctively out of responsibility — like Col. (res.) Lion Bar, who drove to rescue people at the Nova music festival and was killed on the second day of the war. “His wife said, ‘I can’t imagine him behaving any other way. You couldn’t stop him. That’s who he was his whole life.’”

Seven years ago, when Halifa’s mother fell ill, he wrote her life story — gathering memories that revealed her worldview and joys. To his surprise, the project infused her with renewed strength; she gifted copies to all her doctors and improved for a year. He realized the healing potential of documenting life stories and devoted himself to the work.

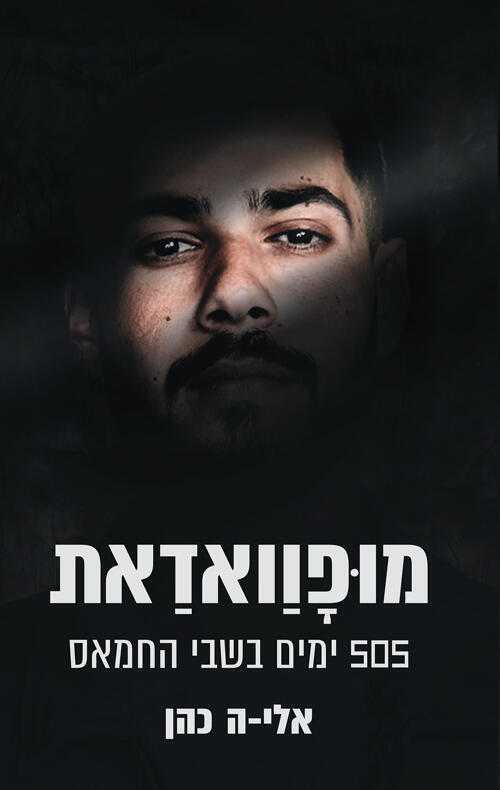

He has now written more than 200 biographies, and eventually was asked to write the stories of two returned hostages: Eliya Cohen, released in February, and Elkana Bohbot, returned last month in the latest hostage deal. Cohen’s book, “Negotiations,” has sold more than 40,000 copies. Bohbot’s book will be published soon.

How do you approach someone who has undergone such trauma?

“I’ve written over 200 life stories, including for Holocaust survivors. You never start working in the first meeting. He doesn’t know you yet, and you’re asking him to reveal his deepest secrets. It’s not an interview; it’s a conversation. Once the conversation flows, they open up.”

He recalls preparing to meet Cohen: “He’s a young man who was held hostage. How do I receive him? He wanted to come to my place, so I left the door open. I didn’t go downstairs to meet him so he wouldn’t lose his independence. For 505 days, he had none. He walks in, we hug and it works.”

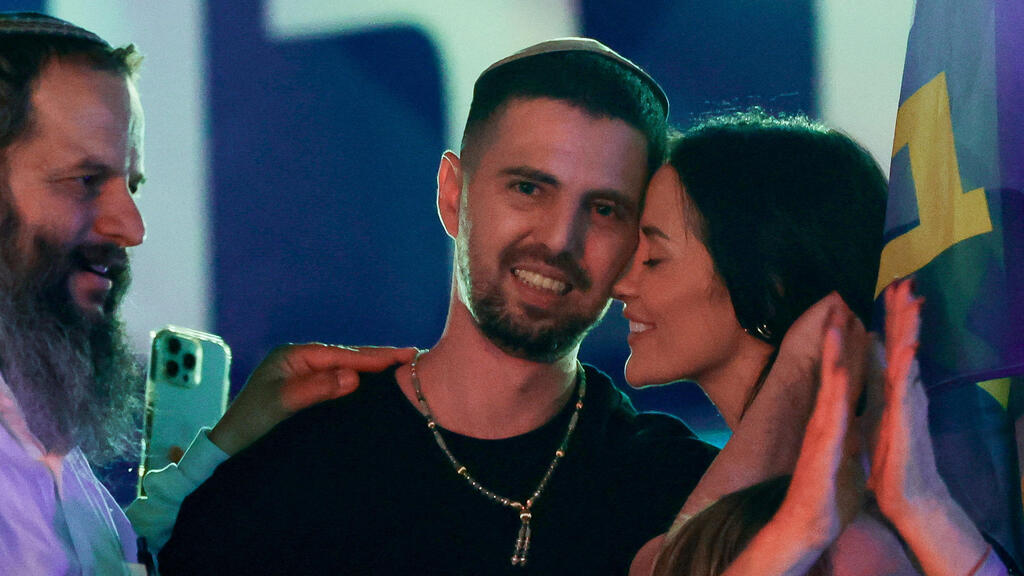

With Bohbot, Halifa was the first person to hear his full story. “His wife sat next to us as he spoke,” he says. “She heard everything at the same time I did.”

Did the freshness of the trauma require a different approach?

“Yes. I try to take them as deep as possible, but carefully.” He gives an example: “He told me, ‘They gave us a bowl of rice and we divided it.’ What does that mean? How do you divide a bowl of rice between four people? Does someone take more? Do you count the grains? I go inside the moment, but I have to watch his emotional limits.”

'You think there’s a bottom, and it goes deeper'

Do these conversations involve psychological support?

“They have support, but I think they need more. You look at a hostage and see someone standing and functioning, but a trigger can bring everything back. They went through the worst things imaginable. You think there is a bottom, and it turns out it goes much deeper.”

Even in the bleakness, Cohen’s dry humor sometimes came through. “He told a terrorist who brought him something, ‘He deserves to be among the Righteous Among the Nations, maybe we’ll recommend him.’ Cynicism helps the reader breathe.”

Halifa understands their urgency to publish. “A book is the most accessible experience. Historical documents are limited. A 240-page book with dialogue conveys it best.”

Even so, certain moments broke you.

“When Eliya spoke in his mind to Ziv, his partner — because he believed she had been murdered — he said, ‘I’ll meet someone else, I’ll build a home, I won’t give up.’ And she was there, sitting next to us. I still dream about it.”

Cohen once called him at 2 a.m. “He said he remembered something about his flip-flops. I told him, ‘Call me whenever you need.’ It shows he’s not sleeping well.”

'Writing it means living it'

Did you feel like you were living the captivity yourself?

“When you write it, you live it. Otherwise, it won’t reach the reader. You imagine your own child in that situation. The helplessness, the rage, the fear — and then you can write it.”

Asked about the difference between Cohen and Bohbot, he says, “Elkana has a child. It’s a different drama. His wife is a Colombian convert, and suddenly she becomes a symbol of the Jewish people’s struggle.”

Did the work change your worldview?

“For me, it’s not about right or wrong. I understand every side. Among the hostages, too, there are conflicting interests. When one hostage is released, other parents feel jealous. They can’t say it out loud, but they feel it.”

He distances himself from political binaries. “The right-left divide is artificial. People say, ‘Let’s conquer Gaza’ because demagoguery is the easiest refuge. Ben-Gvir decided to crack down on prisoners, and minutes later, hostages were beaten. Reality is much more complicated.”

'Writing about the dead was harder than writing about the living'

Despite the emotional toll of the hostage stories, Halifa says writing “Heroes” was harder. “This is bereavement,” he explains. “With hostages, there is suffering but also hope. Here, you move from one death to another. At some point, it was too much. I’m a naturally happy person and felt my joy slipping.”

Sometimes, he says, bereavement is only one layer of many pains. “The one telling the story is often the spouse or parents, and relationships aren’t always good. Sometimes the parents and spouse sit shiva separately. There are divorced parents, and mothers want me to write things about a father who wasn’t present. You need to make clear this is not a settling of scores.”

Anger often bubbles beneath the grief. “People died because of failures. Everything collapsed. I finish the book with the story of Sivan Elkabetz from Kibbutz Kfar Aza— a reminder that behind all the heroism, many were not saved. There is no triumph here. Only loss.”

'It wasn’t fair to him — that’s when I realized I had a problem'

When did you realize it was too much?

“One man complained he was frustrated about a delay. I snapped. I told him, ‘You’re frustrated? Let me give you five phone numbers of bereaved parents. Call them and you won’t be frustrated anymore.’ It was completely inappropriate. He wasn’t at fault. That’s when I understood I needed to calm down. It was getting to me too much.”

Still, there is meaning.

“You go to events and see lines of people waiting for a signature from the person whose story you helped tell. Then you know you succeeded.”

Would you want to sign the books too?

“No. It’s theirs. They lived it. I didn’t even go to all the book events. I’m like a surrogate mother — the child belongs to them.”