About a year after the October 7 massacre, while the entire country was swinging from one permission to announce the death of a soldier to another, and her brother, Sergeant 1st Class Ran Gvili was identified as a dead hostage in Gaza, Shira Gvili had a dream.

“I dreamed that I was in a car with Rani, and he was sitting in the front seat and I was in the back, and I was shouting to him: ‘Rani, how wonderful that you are home. Everyone thought you were dead. You know you’re an icon, and they’re going to make a Hollywood movie about you? I love you, and how wonderful that you are here.’ Then I asked him: ‘No one saw you. Who were you with in captivity? How did you suddenly come back?’ And he answered: ‘I was only with Emily.’ And I said to him: ‘So, how is she? Is she okay? What about her, is she alive?’ And he answered: ‘She’s fine, she’s good, they took care of her.’”

4 View gallery

Shira Gvili is fighting to bring her brother home; Seen here in front of his portrait

(Photo: Herzl Joseph)

“I texted our mom: ‘You won’t believe the dream I had. Rani told me Emily is okay.’ And mom said to me: ‘Do you know who this Emily is?’ There was a little girl who returned named Emily Hand, but we understood that Rani wasn’t referring to her, but to Emily Damari, whom at that time I didn’t know at all, because not much was talked about her. We didn’t know what happened to her, and who she was there with, and suddenly Rani sent me a message about her. Later I understood that this was not a coincidence. They were the only police officers who were kidnapped.”

Did you tell Emily or her parents?

“I didn’t tell her parents, because I remember people were telling me dreams that Rani would come back, and it became a key for hope for me, and I didn’t want that on my conscience if it didn’t come true. After she returned I tried to contact her, and it didn’t happen. It will happen.”

It’s not easy, to say the least, to be the family of the last killed hostage in Gaza, especially after two and a half years of war. In the background there are always despairing examples of those who never returned or those who took more than a decade to bring back.

“At first there were 255 hostages,” Shira Gvili says this week, in her first in‑depth interview. “There were 255 families, so my voice alone wasn’t needed. Everyone supported one another. Now I have to teach myself how to scream, while at the same time we are at a loss and also very sad.

4 View gallery

Shira with Ran: 'When Rani was here every Thursday or Friday there was a party — friends and Mizrahi songs, and always music at full volume'

“It’s not simple to look at the other families, who have become part of us, starting rehabilitation. Each of the returnees moves forward, begins to make a living, lifts themselves up, and we’re not there yet. Every Saturday we have to be at the rally in the Negev and on Friday at the Kabbalat Shabbat in the square. All the families are with us, but in the general public not everyone cares, not everyone knows there’s a last hostage. I ride in a taxi say: ‘I am a sister of a hostage,’ and the driver says: ‘Oh, everyone returned.’ I talk to people, and they ask: ‘Who is Rani?’ What does that mean? That’s my brother and he’s still there.”

Are you afraid he will be like Ron Arad?

“I’m afraid that he’ll remain there a long time, and that we’ll get used to it and that’s scary. That must not happen.”

From Meitar to Mar-a-Lago

In her family’s eyes, she says, it was not a surprise that Sergeant first Class Gvili remained last. “The moment they brought back the late Colonel (res.) Asaf Hamami we knew Rani would be the last to return, but we didn’t imagine it would take so long. We were sure a day or two. Rani is the most. For us he is a symbol of courage and rescue, for everyone who fought on October 7. Even for Hamas he is a symbol: ‘look how we defeated you.’ Rani, like Hamami, is part of their game. That’s why it’s necessary and important to bring him home.”

The Gvilis are making every effort to make their cry heard. The parents — Tali, a successful lawyer, and Itzik, who until the last hostage deal served as director of Development and Infrastructure in the Idan HaNegev Industrial Park — left all their work for the struggle. But until last October, Shira, 24, was not involved in the battle that only her parents were heard in.

“At first,” she says, “I didn’t understand the scale of the event. I went through a process to talk about Rani. At first I didn’t have the tools. Today I am already adapted to this situation, that I am a hostage’s sister, and I’ve built a defense barrier that allows me to detach the emotion and talk about the situation — that Rani is in Gaza.”

So what happened that you got involved?

“When the last phase was half a year ago, Mom was already tired and couldn’t bear all the focus on her, and as they talked about the deal the pressure increased because only she was recognized. Then she asked me to be photographed for the campaign, and then interviews began to be directed to me, and this became my daily routine. The struggle is my ‘coveted job’ and it chose me. I hope I’m doing it well, and Rani is proud of me.”

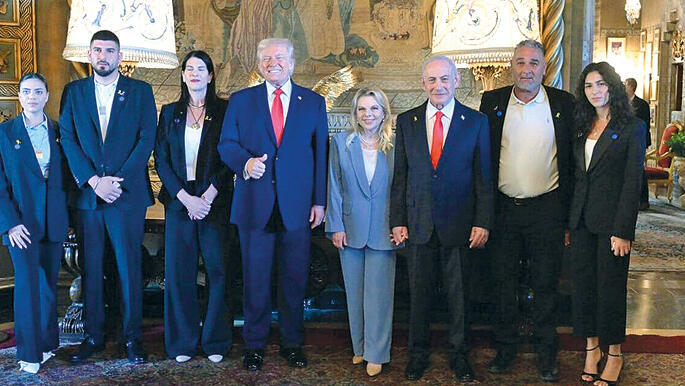

The peak of the effort ended temporarily this week, when she landed in Israel after a mission of efforts in the United States, including meetings with senior U.S. government officials, led by Donald Trump. The original plan included only a one‑week trip with a speech before Congress, meetings at the U.N., and attendance at an event at the White House. In reality, the trip lasted a month.

“Before the first speech, which was at the embassy in Washington,” she recalls, “I wrote down points in English. It’s not that I’m anything special in English, but the moment I went up on stage and had eye contact with the audience, I felt it was strong and powerful. If you come down from the stage and everyone hugs you and talks about what you said, it means they listened.”

“One of the figures I made a personal connection with was Leo Terrell, chair of the U.S. Department of Justice Task Force to Combat Antisemitism. I met him twice. The first time was at an event at the consulate. The moment I went up on stage, he clapped and stood up. Afterwards he sent everyone who approached him to his assistant, and he only gave his business card to me. He approached me and asked: ‘How can I help you?’ and he didn’t expect my answer: ‘How can I help you?’ Because in my eyes it comes together. If we want Rani at home, we have to deal with antisemitism.

“He told me that this was the first time he was asked something like that. I really meant it, and he was moved by me, and we took lots of photos. After we finished in Washington and New York, I flew to Miami, to family I have there and more meetings. This week in New York opened many opportunities. People saw me and asked me to come speak at their conferences. I spoke at SSI (Students Supporting Israel). In Miami there was an event with Joseph Waks, a businessman who helps bereaved families, hostage families and returnees. He held an event together with Tehila Falic (daughter of tycoon Simon Falic) at the Great Synagogue in Miami and Leo was one of the guests.

“When I saw him enter, I got up and asked: ‘Do you remember me?’ and he said: ‘I can’t believe it, what are you doing here? We tried to find you.’ I introduced him to my parents, and they didn’t understand who this man was who praises their daughter so much. He said: ‘Your daughter is a strong and amazing woman and I want to work with her in the future.’ Everyone was in shock and I felt that there was great energy between us.”

And Trump?

“I saw Trump twice. The first time was at the candle‑lighting event at the White House. Trump spoke on stage and said that he had brought everyone back. Then he called Ronen and Orna, the parents of Omer Neutra, amazing people who accompany us and raise our voice in America. Ronen pulled a picture of Rani out of his coat and said to him: ‘Your mission is not yet complete. You haven’t brought everyone back yet — one more hostage remains and that is Rani Gvili.’ You know what courage that is, that instead of saying ‘Thank you,’ you tell the president of the United States: ‘Wait, someone is still here. You haven’t finished the job.’ That was an unforgettable moment for me, one I will forever thank them for.

“I think a lot of people take their foot off the gas the moment they say: ‘Okay, it’s just one body and one person,’ they don’t look at the fact that there is a family here and how important it is to us, to the whole people, that he return. Because if Rani remains there, take into account that October 7 will happen again. As the Goldin family always said: ‘If they had taken care to bring Hadar back, we wouldn’t have reached October 7.’ The same will happen with Rani.”

How did Trump react to these things?

“He was silent and understood, and then we met again, at Mar‑a‑Lago, together with my family. It’s an amazing place, twice the size of Meitar in my opinion, full of really nice people — Witkoff and Kushner and Trump’s aides. You come in determined and even pressured, but Trump shook my hand, asked me what I do in life, was nice and said he knows what Rani means to us and that he’s doing everything to bring him back.

“He knew exactly what Rani did on October 7, knew about the injury during the battle and also about the earlier injury, and that really moved us. I told him I personally think Rani is alive, and after we spoke he had a press conference in which he said: ‘Rani’s family thinks he’s still alive.’ And that’s a statement. Because as president to say such a thing is to send a message to Hamas: ‘Be careful, we think he’s still alive.’ But words are one thing and actions are another. I believe in actions.”

And then suddenly Phase II.

“The news about that hit me while I was abroad. It was a boom in the heart. I felt like someone was looking me in the eyes and lying. That’s what we’re fighting — that there won’t be Phase II before Rani’s return. And that threw me into thoughts: Is my voice not important? Am I not strong enough? I’m not a politician and I don’t claim to be, and neither are my parents. We are just a family that got into this situation. It was hard for me. I felt like a grain of sand in all of this, and I had no idea what I should do now. There was disappointment — that Rani didn’t have to sacrifice himself for this country if it’s not willing to sacrifice itself for him.”

Who is the real bad guy in this story — Hamas? Maybe the government that’s not pushing?

“I don’t expect anything from Hamas. As for the government, anyone who tells me ‘We’re with you and we’ll do everything’ — it goes in one ear and out the other. Give me intelligence, something to hold on to. Don’t show me insecurity. Bring me my brother. So far I’m only getting pats on the back. But for an injured child, a pat isn’t enough — you need to treat him.”

Your parents are said to be members of Tikvah Forum, Netanyahu supporters. Do they still believe in him?

“It’s not about believers. We want something to hold onto, and when someone says beautiful words, it’s very pleasant. But they also think that until there are actions, to them it’s just air. We don’t believe in wars. Not that I’m saying other families did something bad in their struggle. The fact is, everyone returned. But we don’t believe in not meeting. My parents believe in unity and use anyone they can, and anyone who can give them intelligence about my brother, or say ‘We’re with you,’ they will be there and they will appreciate it. They invest every moment in Rani, but after two and a half years the struggle is much harder. People are tired.”

In hindsight, were mistakes made?

“Every family made a mistake here or there. In the end, everyone wanted their child at home. In our case, for Rani, the intelligence failed. It didn’t bring intelligence about him and didn’t fight hard enough for my brother. And the question is: if it wasn’t important enough to bring him back with everyone else, will it be important enough to bring him back alone?”

Are you meeting with Netanyahu?

“Yes. What can he say? ‘We are doing everything we can.’ Will that help me get over my nerves? No. I prefer to keep my health, and I leave the Knesset and those things to my mother — it’s less about me. Politics doesn’t interest us young people, why? Because everything there is crap, everything there is filth, and everything there is anger, and I think that here change needs to begin. And once there is a real politician who comes and tells me the right agenda, who is there for his people, and not for greed, I’m with him.”

Ran was the shnitzel champ

Shira is now exactly the age of her brother, who is two years older, when he was captured. Their relationship was very close.

Because of his role, the Gvili family, together with other families whose hostages served in the security forces, were asked to keep a low profile. In her view that caused people not to know enough about Ran to this day.

“I would like people to know,” she laughs, “that he’s an annoying brother, that on my phone he’s saved as ‘Genetic Defect,’ and I’m saved to him as ‘Luzi,’ short for Lucifer, the devil. That he loved working with wood, and he had a woodworking workshop at home, where in every free moment he would make a chair, table, bed. No man would have entered my life if Rani didn’t know about it, and the same about him. When he was kidnapped he didn’t have a partner. He did think of someone specific.”

“On October 7 we were exactly intending to book a ticket to South America. We planned to take a trip to Brazil, Mexico and Colombia. We decided to travel together because Mom didn’t agree to me going alone, but it also felt most natural to us.

“Rani was a very strong figure in my life. When we were little he would pick me up from school and make me lunch. When I felt danger or sadness, instead of calling dad or mom, it was calling Rani. Rani’s schnitzels were the thing,” she says. “He was a champion at schnitzels. He made them thin, with mustard and garlic, and his secret was amba in the batter. The whole family knows how to cook, but Rani — he’s like our dad, everything he makes is tasty. After school he would make me food, we’d sit and watch goofy movies that he picked — action films like he loved to watch. And then, in the evening, he would play guitar for himself in the living room. Not a performance or anything. That was his moment to be alone.”

When Gvili is asked to describe their home before October 7, she says without hesitation, ‘a happy home.’

“When Rani was here every Thursday or Friday there was a party — friends and Mizrahi songs, and always music at full volume. Friday afternoon, the whole family needs to be at home, and everyone cleans and cooks, and there’s always Amir Benayon or Shlomi Shabat in the background. Dad and I would be cleaning and suddenly Rani would come home in his uniform.

“I think we were a very happy family. Like, even today we’re happy, but sad. We don’t have parties anymore, and no songs on Friday. We still do kiddush and Friday meals, and holidays we always leave him a chair, and the whole house has his photos — even ones people painted us. We even have black humor like: ‘He didn’t bring his passport to Gaza, that’s why he’s still stuck there.’”

The siblings also spent October 6 together.

Gvili was then working as a commercial designer at Urbanica and simultaneously as a bouncer at The Forum club in Be’er Sheba. Rani, who carried a shoulder injury from a motorcycle accident, was celebrating a friend’s birthday. When they returned home they went to sleep in adjoining rooms. Rani, she says, had a dream that Shira would leave the house and he would break the wall between the rooms and turn the whole thing into a suite. After he was kidnapped, the house in Meitar underwent prolonged renovations that still haven’t finished, but Rani’s room — the suite — already waits for him.

“At 6:30 a.m. when the sirens began,” Gvili describes, “we all went down to the shelter, which is our oldest brother Omri’s room. We got into his bed because he was on duty with the police, and we went back to sleep, but Rani got so many messages that he understood something bigger was happening. He went upstairs, put on his uniform, and my father said to him: ‘Where are you going?’ And my mother said: ‘You’re injured, how will you fight?’ I remember he raised and lowered his hand, in a motion from the shoulder, and said to her: ‘Here, I can move my hand.’ You couldn’t fight him, and they let him go.”

According to what is known, Gvili drove to the police station in Be’er Sheba to arm himself, and from there continued to the areas near the border communities where there was fighting. He arrived with another fighter at the Sa’ad Junction gas station, where they operated at risk to rescue and evacuate dozens of Nova survivors. Afterwards he reached the area of Kibbutz Alumim, where he and his comrade were ambushed and he was seriously wounded in his hand and leg. Meanwhile he managed to eliminate at least 14 terrorists.

His last message was sent to a close friend at 10:30 a.m.: “I’m still in an area full of terrorists.” Since then his fate has not been known.

“We don’t know anything,” says his sister. “Every clue has been ruled out. Everything we thought we knew, we actually didn’t know. Even when hostages returned we didn’t get anything, and that’s the problematic part of the story. It’s like the earth swallowed him up. We pray he’s alive, but there’s no intelligence here or there. There are recordings from Gaza on October 7, a picture of him lying on a motorcycle and behind him a hospital. It’s not clear if he’s unconscious or, God forbid, dead. From the government and intelligence perspective it’s certain he is not among the living, but something in our hearts hasn’t accepted it. If you know he is not alive, then where is he? If you know about every hostage, then where is Rani? Why do they try to find him and then not find him?

“When we were updated that he was not among the corpses or in hospitals, we said: ‘Okay, he’s a hostage, he will surely manage.’ Then they told us he is probably not alive. That was on January 30, 2024. Exactly two years ago. To this day I don’t believe it. How can you believe something you haven’t seen?”

Living another person’s life

It is not accidental that the public was not exposed to the young Gvili until now. “In the first two years,” she says, “I went through a process with myself. I pretty much denied the situation. I focused on my own healing.” As part of that, she flew alone to India for half a year. “People didn’t understand how I could,” she shares candidly, “but one day I just decided to fly. I felt I owed it to myself, and people judged me for it. They said, ‘How dare she go and leave her family like that.’ I couldn’t bear the intense reality. I needed for a moment to live someone else’s life. Today I wouldn’t travel for such a long time. So it felt right to me then.”

What did your parents say?

“At first they didn’t agree that I would fly. They said a week or two, and then they understood that I was on a healing journey with myself. Because Rani wasn’t just a brother — he was my whole world. Abroad I suddenly smiled for the first time, was exposed to myself, lived without fear, pushed boundaries.”

In India she met others like her. “Family members of hostages, Nova survivors, reserve soldiers. There were people who said I served as an inspiration to them, because I gave them a different perspective on life, on strength and coping with loss. That even if it’s hard, we won’t let it defeat us.”

After she returned to Israel, she moved to central Tel Aviv — both to create an anchor point for the family during the struggle at Hostages’ Square and to live the life of a normal young woman. She has no visible signs of the struggle on her balcony, and neighbors only discovered who she is when they ran into her by chance at protests.

At the beginning, she says, she was having heart‑to‑heart talks with her brother.

“I used to talk to him about fears. I told him that I am no longer afraid of anything. That no matter what harms me, nothing will happen to me, because I already received the most painful blow.”

After the return of hostage Sudthisak Rinthalak, the Gvili family decided in cooperation with the Hostages and Missing Families Forum to move the Saturday gathering from Hostages’ Square in Tel Aviv to Keshet Junction in Sha’ar HaNegev, and yes, there is also a financial issue. Donations have decreased significantly, and the struggle headquarters cannot produce a weekly rally costing 200,000 shekels like in the past. On Fridays, each kibbutz near the Gaza border takes responsibility for producing the Kabbalat Shabbat at Hostages’ Square until Rani’s return.

Are you jealous of families that have had their loved ones return?

I am not in competition. All the returnees are part of my family, and meeting them in real life is as if Rani came home. On the days they returned I collapsed, but immediately you tell yourself: ‘Wait, Shira, what do you have? Look at them at home, how wonderful.’ Especially when I am two and a half years into this and know each and every one of the hostages. God forbid I would be upset that they are home.”

What about your dreams of studying psychology?

“For now I put them aside. This reality gave me tools to understand I want to help people, but there are bumps. I started studying for the psychometric exam, and then boom — the deal was signed and everything resurfaced, and I really didn’t have the attention to study, so I removed the task from off me. On the other hand, I don’t sit at home and cry about my fate. I get up in the morning with a smile and go to sleep with a smile, because I know I’m fighting. In the middle I am very sad. I live a life I don’t wish on anyone. Sleepless nights, waking up sweaty from nightmares, anxiety attacks. When I feel good, my conscience attacks. It’s like I’m not allowed to feel good, because Rani is there.

“I went through a big trauma in my life, and it’s very hard to look at myself from the side and say I deserve to be happy again, or to treat myself to a party or a girls’ night. I do it because it’s impossible to deal with the sadness for so long. I try to clear my head and talk about ‘light’ things, but it’s accompanied by a lot of guilt.”

Relationships?

“I had a few attempts after October 7, but it didn’t work, because no one can understand what I’m experiencing. If you weren’t there, you can’t really understand me. And I’m not open enough to tell what I’m going through to someone who wasn’t there.”

Have you visited Alumim, the kibbutz from which Rani was kidnapped after defending it?

“No. I was twice in the Nova area. The moment I reached the area where Rani was kidnapped, I couldn’t get out of the car. It was very hard for me to stand there, when I am here and he’s there.”

What do you want the public to do?

“To not continue with routine. To talk, to ask to know who Rani is, to still go with the yellow pins, to still wave signs and stand at junctions. Maybe I can’t demand that after two and a half years, because we are the last, but this is my request: to remain in that format.”

Are you afraid that there will be a day when no one will come to the rally?

“Of course. On the day that happens, if it happens, I can say goodbye to Israel. It’s not just about me, it’s like we all are gone. You don’t just hear all the speeches begin with ‘how happy I am that you’re here,’ ‘how excited I am to see you here.’ We can’t imagine that people care as much as we do that Rani will return home. And to decision‑makers I want to say we are tired. We didn’t choose to be in this situation and it’s your responsibility to bring him home. Don’t abandon us again.”