On the afternoon of Oct. 29, 1957, a routine plenary session of the Knesset was interrupted by an explosion that reverberated through the assembly chamber, wounded the prime minister and three cabinet ministers and brought parliamentary proceedings to a sudden halt in the most serious act of violence ever carried out inside the legislature.

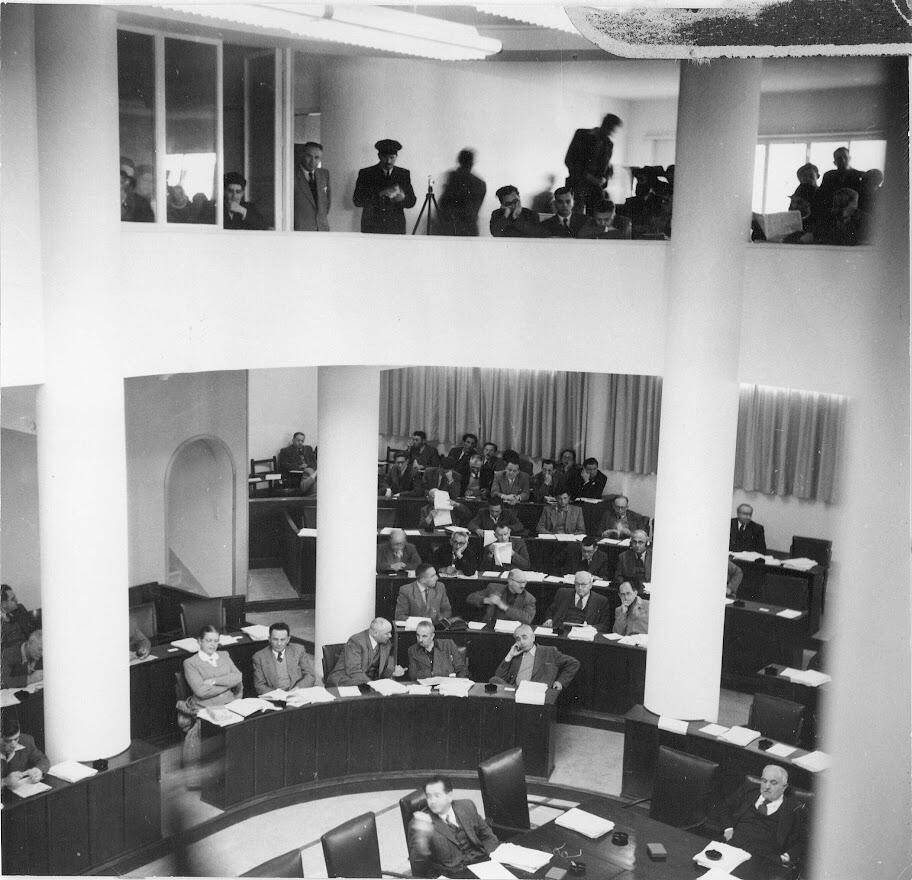

The explosion occurred shortly after 6 p.m. at Beit Frumin on King George Street, the temporary home of the Knesset during the state’s first decade. A hand grenade thrown from the visitors’ gallery landed between the speaker’s podium and the government table and detonated moments later, filling the chamber with smoke, debris and shrapnel as members dove to the floor and aides rushed toward the injured.

Minister of Religious Affairs Moshe Shapira, who was standing closest to the blast, was seriously wounded by shrapnel in the abdomen and collapsed at his seat. Transport Minister Moshe Carmel, seated nearby, suffered lighter injuries and a broken hand from the force of the explosion. Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion and Foreign Minister Golda Meir were struck by fragments and sustained light injuries. Education Minister Zalman Aran was unharmed after rising from his chair moments before the grenade exploded.

MK Yitzhak Rafael, who had been speaking when the grenade was thrown, saw the object descending toward the chamber, shouted “Bomb!” and dropped to the floor. Vice Speaker Israel Yeshayahu-Sharabi, who was chairing the session, suspended proceedings at 6:17 p.m.

The chamber descended into confusion. Members shouted for doctors. Some crawled beneath desks while others rushed toward the wounded ministers. MK Dr. Samson Unichman, a physician by training, provided emergency treatment to Shapira and then to Carmel, improvising medical aid amid shortages of basic supplies. Meir asked that the others be treated first and later received assistance from MK Eliezer Shostak. Ben-Gurion, bleeding but conscious, was escorted out of the building to a waiting vehicle and taken to Hadassah Hospital. Shapira, Carmel and Meir were also evacuated for medical treatment.

The man who threw the grenade, Moshe Dwek, was seized immediately by people seated near him in the visitors’ gallery who saw him carry out the act. Security personnel conducting a routine patrol inside the building took him into custody and began an initial interrogation, which was recorded. He appeared distraught, cried intermittently and apologized.

At the time of the attack, security arrangements at Beit Frumin were minimal. Two unarmed guards were stationed at the entrance. Visitors were required to present identification but were not searched, and bags were not inspected. The visitors’ gallery was separated from the chamber only by a low railing, providing a clear and unobstructed line of sight to the ministers seated below. Dwek had entered the building without difficulty and had visited the Knesset previously.

Outside Beit Frumin, crowds gathered within minutes of the explosion as word spread through the city. Police cordoned off King George Street and struggled to maintain order. Some members of the crowd attempted to attack Dwek as he was removed from the building, shouting accusations and striking him before ushers and police intervened. Kol Yisrael radio reported the incident at 7 p.m., stating that the motive did not appear to be nationalist.

After the chamber was cleared of debris, shattered furniture and bloodstained papers, the Knesset reconvened at 8:52 p.m., several hours after the attack, and formally completed the day’s agenda.

The attack came against a background of earlier warnings and incidents. In 1949, an armed immigrant entered the provisional Knesset in Tel Aviv before being overpowered. In 1951, members of an extremist religious underground attempted to damage the parliament. In March 1956, Knesset officer Yona Chazur warned Speaker Yosef Sprinzak in writing that under existing conditions, a person could enter the visitors’ gallery and throw a grenade into the chamber without effective means of prevention. No structural changes were made.

Authorities initially examined whether the attack was linked to broader political events, as the date coincided with the first anniversary of both the Suez Crisis and the Kafr Qasim incident. Police soon informed Speaker Sprinzak that the suspect was mentally unstable and that no nationalist motive had been identified.

As investigators reconstructed the events, details of Dwek’s background emerged. Born in 1933 in Aleppo, the third of seven children, he immigrated alone at age 13 as part of Youth Aliyah and lived on kibbutzim before serving in the IDF Communications Corps and taking part in fighting during the War of Independence. His family joined him in 1950 and settled in Pardesiya. After military service, he worked briefly as an elementary school teacher but left due to worsening medical problems.

In the years before the attack, Dwek pursued a legal battle against the Jewish Agency, claiming that an abdominal injury sustained as a youth had left him disabled. His lawsuit and appeal were rejected. He later attempted to leave the country illegally, was detained and sent threatening letters to judicial officials. In May 1956, he warned Supreme Court President Yitzhak Olshan that institutions and individuals would be physically harmed if his case was not reopened. He was arrested and hospitalized for psychiatric observation before being released.

During questioning after the attack, Dwek said he had acted alone and wanted to force public attention on what he described as the injustice done to him. Two additional hand grenades were later found hidden near his home, stolen from the IDF.

While hospitalized at Hadassah, Ben-Gurion wrote a handwritten letter during the night to Dwek’s parents, which was delivered the following day by a police officer and published in the press. “I know that you grieve, together with all the people of Israel, over the despicable and foolish crime your son committed yesterday,” he wrote. “This is not your fault. You live in a state where justice and integrity prevail, and I hope that no harm will come to you or to your other sons.”

Ten days after the attack, Dwek wrote from prison to Ben-Gurion, acknowledging responsibility. “I was brought to a state where I myself threw a bomb into the Knesset hall,” he wrote. “In this act I became a shedder of blood. For this there is for me no forgiveness and no atonement.”

Ben-Gurion did not reply immediately. Months later, responding privately to a letter from Dwek’s parents seeking clemency, he wrote that “the act he committed is a grave crime, and only the court can judge him,” adding, “I myself bear no grudge against your son. I am sorry for him that he chose a bad path.”

Dwek was charged under the Criminal Law Ordinance and underwent psychiatric evaluations. Despite earlier hospitalizations, experts found him competent to stand trial. In August 1958, he was sentenced to 15 years in prison, part of which he served in psychiatric institutions. Requests for a retrial and repeated petitions for clemency were denied.

The attack prompted immediate security changes at the Knesset. An armored barrier was installed in the visitors’ gallery, and entry procedures were revised. In 1958, the Knesset Guard was formally established, and a state unit for the protection of public figures was created within the Shin Bet.

Ben-Gurion, Meir and Carmel returned to their duties after brief hospitalizations. Shapira underwent a prolonged recovery and later added the name Haim to his given name.

For decades, the extent of the correspondence between Ben-Gurion and the man who had tried to kill him remained largely unknown. The letters became public only years later, after documents surfaced in archival collections, revealing an extended exchange that continued long after the trial and sentencing.

In that correspondence, Ben-Gurion wrote to Dwek, “I forgive you for what you did to me, and I have no resentment against you. But you must understand that you sinned not only against individuals, but against the peace of the state and the Knesset, and I have no authority to forgive that.”

In a 1968 letter to Justice Minister Yaakov Shimshon Shapira, written more than a decade after the attack, Ben-Gurion urged leniency. “You may be surprised that I turn to you,” he wrote. “You surely remember the case of the bomb thrown by Moshe Dwek 11 years ago. It seems to me that it would be right to grant clemency to this young man, for he has already paid his debt.”

In a separate letter to Dwek, Ben-Gurion reported that he had appealed to the justice minister and added, “I hope — I am not certain — that your request will be examined.”

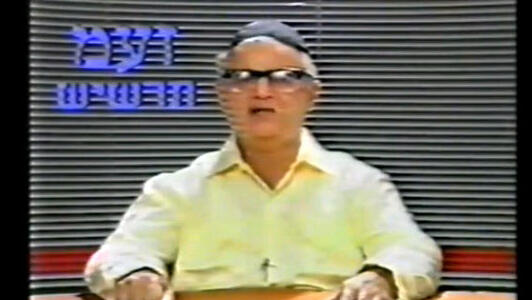

Dwek was ultimately not pardoned at that time. He was released after serving his sentence and later lived in Netanya. In 1988, he headed a small party named Tarshish in elections to the 12th Knesset. Its ballot symbol was the Hebrew word זעמ, meaning rage or fury. The party received 1,654 votes and did not enter the Knesset.

Dwek died in 2003. Ben-Gurion died in 1973.