As Jews around the world light Hanukkah candles to celebrate resilience and identity, the ruins of Apamea — an ancient city in modern‑day Syria — reveal a chapter of Jewish history that complicates common perceptions of Jewish life under Hellenistic influence.

Apamea was founded in the 3rd century BCE by Antiochus I Soter (280–261 BCE), the great‑grandfather of Antiochus IV Epiphanes, the Seleucid ruler whose later policies in Judea ignited deep conflict. Antiochus I established the city on the Orontes River as part of a broader strategy to strengthen Seleucid control across Asia Minor. Built on a plateau by the Marsyas River at a crossroads of trade and travel, Apamea became a major commercial and strategic centre on the Great Southern Highway linking inland Anatolia to Mediterranean ports.

By the beginning of the common era, Apamea was a hub of regional commerce and culture. The Jewish presence there appears in both historical and archaeological sources. The first‑century Jewish historian Flavius Josephus described the city as part of a volatile world of Roman civil war and shifting alliances. In his Jewish War, Josephus recounts events near Apamea during the tumultuous aftermath of Julius Caesar’s death:

“About the same time disturbances broke out in Syria… a great war began near Apamea… Cassius arrived in Syria to take over the armies near Apamea… And after raising the siege, he won over both Bassus and Murcus, and descending upon the cities, he collected arms and soldiers from them, and imposed heavy tribute upon them.”

Josephus also noted that Apamea had one of the largest Jewish populations outside Judea, and that during the First Jewish–Roman War (66–73 CE) local inhabitants protected Jewish residents from harm rather than surrendering them to violence — a striking account given the broader turbulence of the era.

While narrative history provides glimpses, real evidence of Jewish life emerged with archaeological discoveries. In 1934, Belgian archaeologists unearthed a 4th‑century synagogue beside Apamea’s great Cardo Maximus, the city’s main colonnaded street. Its prominent location near the city’s civic heart suggests that Jews were integrated into public life, far from marginalized quarters.

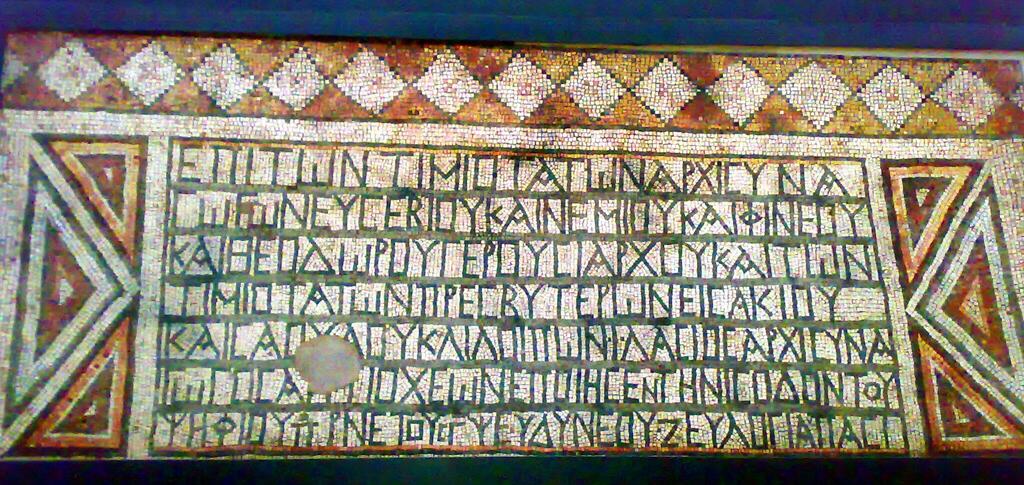

The synagogue’s expansive mosaic floor, almost 120 square metres in area, was richly patterned and sub‑divided into geometric carpets and inscribed panels. Unlike some contemporaneous synagogues — such as at Dura Europos, known for biblical murals — Apamea’s floor respected the Jewish prohibition on figural representation; apart from a small menorah motif, its artistry could resemble that of a wealthy Hellenistic villa. What set it apart were the donor inscriptions in Greek — the lingua franca of the Hellenistic world — that both anchored it in Jewish religious identity and testified to an engaged and flourishing community.

One inscription honours Iiasios son of Eisakos, archisynagogos of Antioch, for commissioning the entrance mosaic “for the salvation of Photion (wife) and children … and peace and mercy on all your blessed community.” Other inscriptions credit female donors — Abrosia, Domnina, Eupithis, Diogenesis and Saprika — each dedicating portions of the mosaic for family welfare and the well‑being of the community. These texts not only preserve ancient names but reveal the active roles of women as prominent contributors in the congregation.

These inscriptions and the synagogue’s central urban presence suggest that Jews in Apamea were neither passive nor hidden in a world dominated by Hellenistic culture. They maintained religious distinctiveness, invested in monumental space, and engaged publicly in a cosmopolitan environment shaped by Greek language, architecture and commerce.

In later centuries, as religious dynamics shifted with the rise of Christianity, the synagogue was covered by a 5th‑century church, reflecting changing cultural and political priorities. Yet the earlier synagogue — preserved underground until its discovery — provides a vivid window into a time when Jewish identity persisted within Hellenistic and Roman society.

Written sources from the period rarely document Jewish life in Asia Minor in detail. Rabbinic literature seldom mentions Jews in the Eastern provinces, and Christian sources often portray Jewish communities through polemical lenses. The donor inscriptions at Apamea, like those found at archaeological sites such as Antioch and Sardis, offer rare and direct evidence of Jewish community structure, identity and agency during Late Antiquity.

In more recent history, Jewish presence in Syria endured until the 20th century, when escalating anti‑Jewish violence during and after Syrian independence led to the near disappearance of local Jewish communities. Even today only a handful of Jews are believed to remain in the country, with many making aliyah to Israel in recent decades.

Apamea itself — once a crossroads of Hellenistic and Roman influence — now lies in ruins near the modern town of Qala’at Mudiq, its archaeological remains scarred by time and conflict. Still, the surviving mosaics and inscriptions — housed in the National Museum of Damascus and other collections — continue to speak across millennia.

For Hanukkah — a festival celebrating identity, resilience and continuity — the story of Apamea offers a powerful reminder: that Jewish life in the ancient world was not just one of resistance but also of integration, visibility and community — even under the sweep of dominant cultures that shaped history.