Every Hanukkah, when the candles are lit on the 25th of Kislev, the Jewish world turns its gaze to a familiar moment: a miraculous victory over a foreign empire, the purification of the Temple, and the restoration of religious life in Jerusalem. The holiday commemorates the triumph of Judah Maccabee and his brothers, the sons of an aging priest from Modi’in who dared to rebel against the seemingly unstoppable Seleucid Empire.

It is a story of courage and faith, retold in classrooms and synagogues with bright colors and hopeful melodies. Yet the miracle we celebrate is only the prologue to a much larger tale. What followed those days of light was a century-long drama of ambition, conquest, family loyalty, and bitter betrayal. The Hasmonean dynasty, born out of devotion to God and the yearning for freedom, built a Jewish kingdom unlike any seen since biblical times. It also tore itself apart so violently that Rome stepped in and ended Jewish sovereignty for nearly two thousand years.

To understand how a revolution of principle became a monarchy of blood, it helps to follow the arc from the first spark of rebellion to the final Hasmonean queen.

The spark that became a kingdom

In the second century BCE, Judea was one of many provinces ruled by the Seleucid Empire, a Hellenistic state carved from the ruins of Alexander the Great’s world-spanning conquests. For generations, Jews lived under a loose arrangement that allowed religious freedom and Temple worship. The Greeks changed governments often, but they generally left local customs intact.

Then came Antiochus IV.

A ruler shaken by military disaster and eager to assert control, he tried to bind his empire through enforced cultural unity. In Jerusalem he outlawed Jewish ritual practice and desecrated the Temple. These policies, which appear baffling even to historians today, ignited fury among a people long accustomed to worshiping in their own way.

Mattathias, a priest from Modi’in, refused to obey imperial decrees. With his five sons he declared open rebellion, rallying others with a call that became legendary: “Whoever is for God, follow me.” After Mattathias died, leadership passed naturally to his sons, who remained united through years of war. Judah Maccabee took command, using guerrilla tactics against Seleucid garrisons and inspiring many to join the resistance.

By 164 BCE, Judah entered Jerusalem, restored the Temple, and revived Jewish ritual life. The celebration that followed, later known as Hanukkah, marked a cultural and spiritual victory. But it did not end the war, nor did it secure independence.

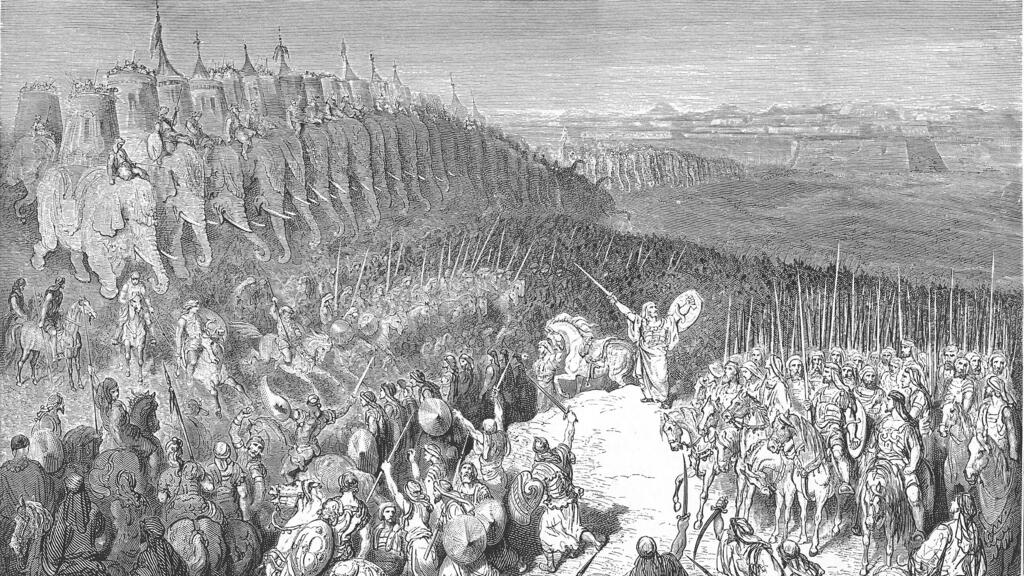

One brother died in battle after another. Judah fell at Elasa. Eleazar died beneath a charging elephant. Jonathan was murdered after years of diplomatic maneuvering. Only the last brother, Simon, lived to see independence secured. Under his leadership, the Seleucids agreed to grant Judea autonomy, the right to mint its own coinage, and exemption from imperial taxes. The Jewish People, for the first time in centuries, had a state of their own.

Simon was murdered six years later. His son, John Hyrcanus, survived the ambush and inherited a fragile, newly independent kingdom.

Power consolidated, culture transformed

Hyrcanus ruled longer than any of his predecessors, and under him the Hasmonean state changed drastically. At first he governed as his father had, acting as both High Priest and national leader, a model acceptable to a population that still saw its rulers as guardians of religious life. But over time he expanded his armies, enacted territorial conquests, and adopted cultural practices common among Hellenistic monarchs.

This shift widened social divisions already present in Judean society. The Pharisees, a movement focused on traditional law and ethical rigor, clashed with the Sadducees, a priestly elite associated with the Temple. The Hasmoneans increasingly aligned with the latter, a choice that distanced the rulers from the broader public.

When Hyrcanus died, he attempted to leave power to his wife, but his son Judah Aristobulus imprisoned her and seized the throne. Aristobulus reigned for only a year, but his widow, Salome Alexandra, would later emerge as one of the dynasty’s most important figures. After Aristobulus’ death she married his brother Alexander Jannaeus, a king defined by warfare and iron-fisted rule.

Jannaeus expanded the Hasmonean kingdom to its greatest territorial extent, conquering coastal cities and regions east of the Jordan. He also deepened internal strife. His reliance on foreign mercenaries, willingness to execute opponents, and open contempt for the Pharisees ignited two major rebellions. According to ancient accounts, after crushing one uprising he had hundreds of rebels executed in front of him during a feast.

His death from disease ended nearly three decades of turmoil, and his widow, Salome Alexandra, finally brought peace.

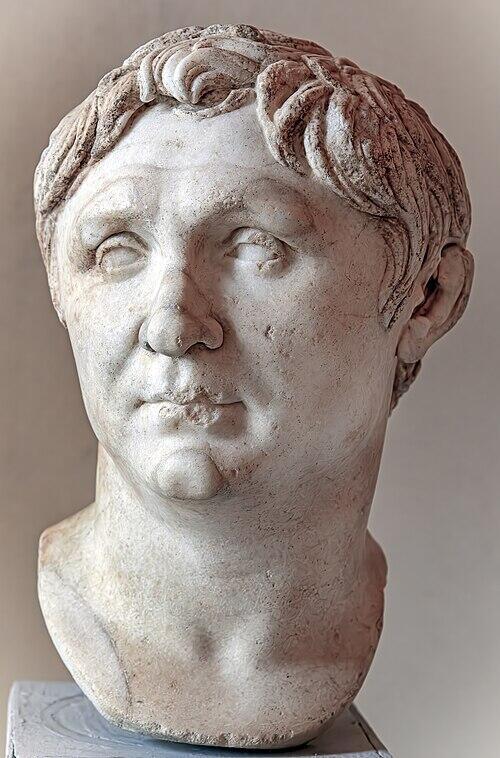

Queen Salome Alexandra ruled for nine years, the only woman to hold full power in the Hasmonean kingdom. She pursued a markedly different approach from her husband. By empowering the Pharisees and promoting legal scholarship, she gained the trust of the people and restored stability. Under her leadership Judea enjoyed rare prosperity, a calm nearly forgotten in the decades of war.

Yet beneath the surface, cracks remained. Her elder son, Hyrcanus II, became High Priest, a position that gave him religious authority but little charisma. Her younger son, Aristobulus II, emerged as a gifted and ambitious military leader. When the queen’s health declined, Aristobulus moved quickly. He seized fortresses, gathered a loyal army, and, after his mother’s death, declared himself king.

Brothers collide, Rome walks in

Hyrcanus II seemed content at first to step aside. He agreed to remain High Priest while his brother ruled. But he had influential advisers, none more important than Antipater, a political operator from Idumea who saw opportunity in the family divide. Under his pressure Hyrcanus reconsidered and sought to reclaim the throne.

What followed was a civil war that hollowed out the kingdom. Both brothers plundered sacred treasures, desecrated spaces their ancestors had fought to protect, and recruited foreign allies. The dynasty that began as a defense of religious life had become its own greatest threat.

As the brothers battled, Rome approached. The Roman Republic had been expanding eastward, and its general Pompey the Great was dispatched to impose order on the region. Both Hasmonean brothers appealed to him, asking him to recognize their claim. A third delegation, representing everyday Judeans exhausted by royal corruption, asked Pompey to dismantle the dynasty altogether.

Pompey accepted none of their proposals. Instead he besieged Jerusalem, broke through the defenses after three months, and marched into the Temple’s inner sanctuary. Aristobulus was taken prisoner. Hyrcanus was restored as High Priest, but only as a Roman-dependent official. Judea’s independence was gone.

What remained of the dynasty became entangled in Roman politics. Antipater rose in influence. His son Herod, appointed governor of Galilee, clashed with Hyrcanus and later married Hyrcanus’ granddaughter, Mariamne, a woman celebrated even in hostile sources for her dignity and intelligence.

When Herod became king under Roman authority, he eliminated any remaining Hasmonean claimants. He mutilated Hyrcanus to prevent him from ever serving as High Priest again and executed several members of Mariamne’s family. His marriage to Mariamne deteriorated under mutual suspicion, and he ultimately ordered her death. She died with composure, the last Hasmonean to hold the title of queen.

Her execution marked not just the end of a family, but the extinction of an ideal that had once united a nation. Less than a century later the Temple itself would fall to Rome.

A dynasty remembered in light and shadow

The Hasmonean story is both inspiring and tragic. It begins with a band of faithful brothers who fought for the right to live as Jews and ends with their descendants battling one another in the Temple courts they once sanctified. The dynasty’s early years offer a glimpse of unity and courage that has echoed through Jewish memory for generations. Its later decades remind us how power, when detached from principle, corrodes even the noblest beginnings.

The candles of Hanukkah commemorate a miracle of endurance. The dynasty that grew from that miracle offers a different kind of lesson: the fragility of independence, the risks of unchecked ambition, and the enduring truth that nations often fall not from foreign might, but from the fractures within.