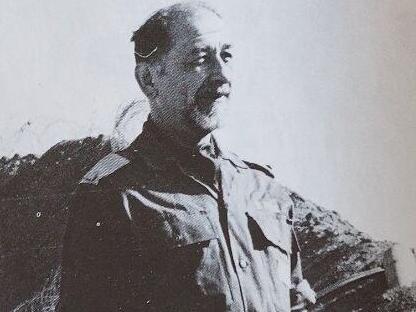

For most of his life, Ze’ev Avni lived under false names, conflicting loyalties and a secret so deep that even his closest colleagues never suspected the truth. Born Wolf Goldstein, he was a Soviet intelligence officer who infiltrated the heart of the young Israeli state — reportedly becoming the only known spy to penetrate Mossad, Israel’s secret intelligence service.

But what makes Avni’s story extraordinary is not only his betrayal. It is the way it ended. After years in an Israeli prison, he renounced communism, embraced Zionism, and spent the rest of his life helping to care for the psychological wounds of Israeli soldiers.

His life — stretching from prewar Latvia to postwar Israel, from the world of espionage to the world of psychiatry — remains one of the strangest tales in the history of Israeli intelligence.

Avni was born Wolf Goldstein in Riga, Latvia, in 1921. His family moved to Switzerland when he was a child, where he grew up in a cultured Jewish home. But while many Jews of that era gravitated toward Zionism, Goldstein turned the other way: he embraced communism.

His older brother, Alex, was already a respected communist organizer in Switzerland. Wolf, eager to prove himself, joined the leftist movement as a teenager, denouncing capitalism, religion and nationalism. According to reports, he viewed himself as an internationalist, devoted to the communist ideal of a classless world — one in which Jewish identity no longer mattered.

During World War II, his fluency in multiple European languages and his loyalty to Marxist ideals reportedly drew the attention of Soviet intelligence. Recruited by the GRU — the Soviet military intelligence agency — he was trained in basic tradecraft: information gathering, coded communication and cover identities.

By the war’s end, the Soviet Union was already eyeing the Middle East as a new arena of influence. With Israel soon to be born, Goldstein was chosen for a daring mission: to become a long-term sleeper agent inside the Jewish state. His orders were simple — build a life, rise in its institutions, and when the time came, provide Moscow with access to its secrets.

To carry out the mission, Goldstein remade himself. He took a new name — Ze’ev Avni, using the Hebrew word for “wolf” — and set out for the Middle East with his wife and young child. The young family immigrated to Israel under the guise of idealistic pioneers seeking to build the new state.

They settled in Kibbutz Hazore’a, one of the communal farming collectives that dotted Israel in its early years. To an outsider, kibbutz life might have seemed idyllic: collective ownership, equality, and shared labor. But for Avni, it also offered perfect camouflage. A kibbutz was the closest thing in Israel to a functioning socialist experiment, and his fervent communist beliefs fit easily within its culture.

Life on a kibbutz meant living collectively — not only sharing property and income, but even raising children together in communal dormitories. The arrangement appealed to Avni’s sense of ideological purity. Yet his zeal soon exceeded that of his neighbors. He joined Mapam, the left-wing party with ties to the Soviet bloc, and according to reports, openly sympathized with Moscow’s policies.

But Avni’s revolutionary enthusiasm became his undoing. At some point, he confided in another kibbutz member — a fellow communist named Yehuda Brieger — and revealed his true mission: that he was spying for the Soviet Union. Brieger, apparently horrified, convened a kibbutz meeting to discuss what to do. In typical kibbutz fashion, the members voted to expel Avni. They refused, however, to inform the Israeli authorities, preferring to resolve the matter internally.

Avni left quietly, without arrest — an omission that would later haunt Israel’s intelligence services.

After leaving the kibbutz, Avni reinvented himself once again. He joined Israel’s Foreign Ministry, beginning a career that would bring him access to diplomatic secrets, intelligence cooperation, and classified communications.

In the 1950s, he served in Israeli embassies in Brussels, Athens and Belgrade. These postings placed him at the intersection of Israel’s young diplomacy and its intelligence networks. Many Mossad operations abroad were coordinated through embassies, giving Avni a front-row seat to the secret workings of the state.

Then came the signal he had been waiting for. According to reports, a Soviet contact approached him on a Brussels street and uttered a prearranged code word — one that meant “activate.”

From that day, Avni began sending information to the GRU. He reportedly passed on diplomatic cables, details of arms deals, and sensitive correspondence about Israel’s relationships with European governments.

His motivations, investigators would later note, were ideological rather than financial. He took no payment from his Soviet handlers. His goal was to advance communism and weaken what he saw as a capitalist state aligned with the West.

Avni’s role within Israel’s diplomatic corps made him invaluable to the Soviets. According to later reports, he was even involved in a Mossad-linked mission known as Operation Damocles — Israel’s covert campaign to stop former Nazi scientists from building ballistic missiles for Egypt in the late 1950s.

Israel, fearing annihilation, had drawn up plans to assassinate or kidnap the German scientists working for Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser. Avni, fluent in German and Swiss-German, was reportedly brought into the operation to assist with coordination in Europe.

But Avni’s loyalties were elsewhere. Egypt was a Soviet ally, and the operation directly threatened Moscow’s regional interests. Avni allegedly sabotaged elements of the mission, leading to failures that set the operation back months.

His Soviet handlers, meanwhile, encouraged him to deepen his ties with Israeli intelligence. His work with Mossad contacts had effectively placed him inside the organization — a feat no other known Soviet spy is believed to have achieved.

Avni’s downfall came not through intercepted messages or foreign tipoffs but through an extraordinary act of intuition.

In 1956, while stationed in Brussels, he returned to Israel on what appeared to be routine business. During a meeting with Isser Harel, then head of the Mossad, Avni mentioned that one of his reasons for the visit was to see his eight-year-old daughter. The remark, by itself, was harmless. But to Harel, a man famed for his instincts and mastery of psychological tactics, something about the answer felt off.

Later, Harel told colleagues that he found the explanation “strangely rehearsed,” as if Avni had offered an unnecessary justification for his presence. Acting on instinct, Harel decided to test his suspicions — without a shred of hard evidence.

He invited Avni for what was presented as an informal follow-up conversation. According to reports, Harel blindfolded him and drove him to a deserted area outside Tel Aviv. There, surrounded by security personnel, Harel launched into an elaborate bluff.

He told Avni that the Mossad had uncovered every detail of his cooperation with Soviet intelligence — the names of his handlers, the messages he had sent, even the dates of his meetings. None of it was verified, but Harel’s delivery was calm and precise, leaving no room for doubt.

When Avni denied everything, Harel pressed harder. He told him the Soviet Union had already betrayed him, trading information about his activities to Western services. The claim was false, but it struck a nerve. To a man whose loyalty to the communist cause had defined his life, the idea of being discarded by the regime he worshiped was devastating.

After hours of pressure, Avni broke. He confessed that he had been recruited by the GRU years earlier, sent to Israel under orders, and had indeed passed information to Soviet contacts in Europe. When he finally asked Harel how the Mossad had discovered him, the spymaster reportedly replied: “We didn’t. You just told us.”

Avni was arrested immediately. The government imposed a strict gag order, and his trial was held behind closed doors. In 1956, he was convicted of espionage and sentenced to 14 years in prison.

The entire operation — a mix of intuition, psychological manipulation and improvisation — became one of the most famous stories inside Israeli intelligence circles. It showcased Harel’s audacity and deep understanding of human weakness, but it also reflected how fragile Avni’s double life had become.

At first, Avni resisted all attempts to extract information. His Soviet training had prepared him for isolation, manipulation and pain. According to accounts from those who worked on the case, his interrogators could not break him through standard methods.

One of them, Yehuda Prague, took a different approach. Rather than applying pressure, he tried to dismantle Avni’s belief system. He showed him a leaked copy of Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev’s famous “Secret Speech” denouncing Joseph Stalin’s brutality — a document that shattered the faith of communists around the world.

For the first time, Avni began to question his convictions. His doubts deepened when his brother Alex, still a loyal communist, visited him in prison. Instead of pride, Alex expressed disgust. “After two thousand years our people have a state,” he reportedly told him. “And the first thing you do is try to destroy it?”

Those moments marked the beginning of Avni’s ideological collapse.

In prison, Avni studied psychology and sociology, earning a degree and developing a fascination with the human mind. Over time, he renounced Marxism entirely and began to see himself not as an agent of revolution but as a potential agent of repair.

He served roughly ten years of his 14-year term before receiving a presidential pardon.

When Avni emerged from prison, Israel was a changed nation — wealthier, more confident, but still scarred by conflict. Determined to prove his loyalty, Avni sought ways to contribute.

In 1973, during the Yom Kippur War, Israel was caught off guard by surprise attacks from Egypt and Syria. The fighting was intense, and many Israeli soldiers suffered severe psychological trauma. At the time, the army had few systems for dealing with combat stress.

Avni volunteered to travel to the Sinai front as a psychologist, counseling soldiers suffering from shock, grief and what would later be called post-traumatic stress disorder. His work, according to reports, made a deep impression on military doctors and officers.

Over the next several years, Avni helped shape what became the IDF’s Mental Health Department, establishing procedures for field counseling and post-combat treatment. Today, that department is regarded as one of the most advanced of its kind in the world.

In interviews later in life, Avni said he viewed his work as a form of atonement. “I wanted to give back to the country I had wronged,” he reportedly said.

Avni later wrote a memoir, False Flag: The Inside Story of the Spy Who Worked for Moscow and the Israelis, co-authored with his former interrogator, Yehuda Prague. The book offered a rare glimpse into the psychology of an ideological spy who turned into a patriot.

He lived quietly in Israel until his death in 2007.

Even in death, Avni’s legacy remains divisive. Some Israelis view him as a traitor who cannot be redeemed. Others see him as a man who underwent a profound transformation and ultimately gave more to the country than he ever took away.

The details of his espionage remain partly classified, and some historians caution against exaggerating his infiltration of Mossad. Still, no other case so fully embodies the contradictions of Israel’s early years — a socialist experiment, a Cold War battlefield, and a refuge for Jews that one of their own once betrayed.

For intelligence historians, Avni’s life stands as an extraordinary parable: the Soviet agent who tried to undermine Israel, then helped heal its soldiers.

In the words of one former intelligence official, “He began by breaking Israel’s trust — and ended by trying to mend its soul.”