Twenty years after Israel’s unilateral disengagement from the Gaza Strip, former residents of Gush Katif — evacuated as children in 2005 — are returning to the area, this time in uniform as reserve soldiers. The emotional return has stirred memories of home for many, even as they navigate destroyed neighborhoods and altered landscapes once filled with life, community and childhood innocence.

Gal Cohen, 28, was seven when his family was forced to leave their home in the northern Gush Katif settlement of Nisanit. Today, he finds himself retracing those childhood memories while on duty.

“Everyone has their hometown,” Cohen said. “I never had that nostalgia after we left. But when we arrived at a beach in Gaza, I told my fellow soldiers, ‘This is where I grew up. This was our childhood beach.’ Back then, I was a kid playing in the sand. Now I’m back in uniform on a security mission.”

Cohen recalled life in what he described as a warm and tightly knit community. His family lived in Dugit, where they had settled after being evacuated from the Sinai settlement of Yamit.

“It was our regular hangout,” he said. “It used to be beautiful, with palm trees and lawns. Now it’s filled with sewage and destruction — but I recognized the exact spot.” Cohen paused there during a reserve tour to take a photo for his mother. “She got emotional and asked when I’d take her back.”

The return has also resurfaced painful memories — mortar attacks on school buses, fears of infiltrations, and the killing of his kindergarten teacher in a terror attack.

On the night of Aug. 14, 2005, Cohen and his family were the last to leave Nisanit. “We knew the soldiers were just doing what the state asked, but we stayed until the last moment,” he said. “On my last reserve tour, I asked to get off at the beach. I smoked a cigarette and looked out at the view — thinking about what it used to be.”

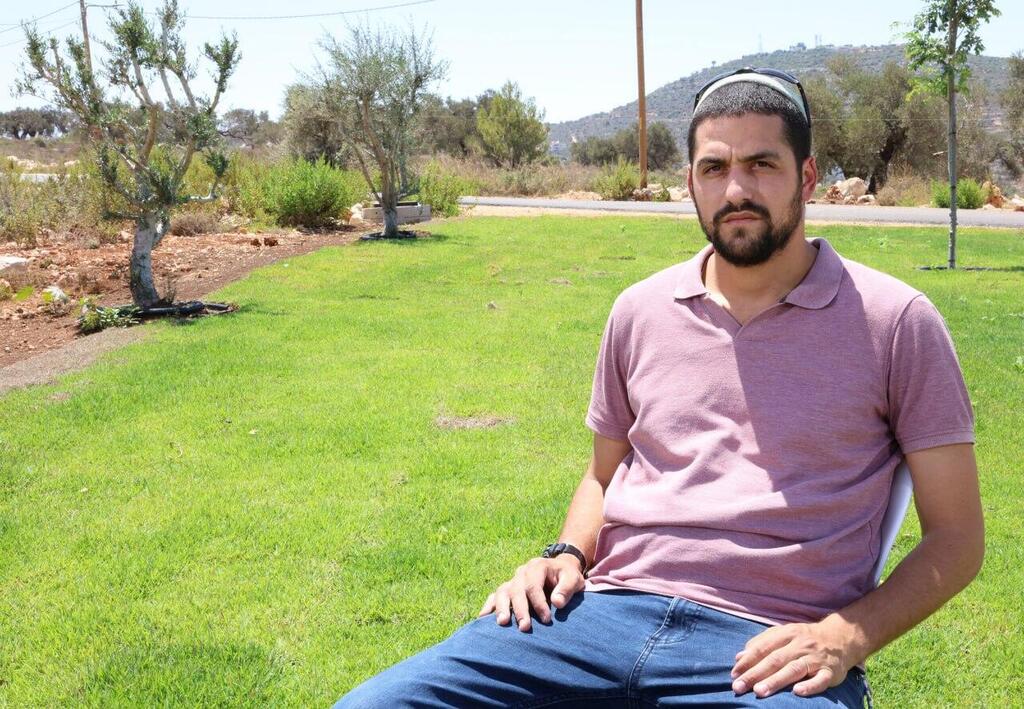

For others, the pull to return never faded. Yochai Vilozny, 37, a father of six living in Carmi Katif, was raised in Moshav Katif, where his father served as the local rabbi. “I always knew I’d come back. We just didn’t know how, and we didn’t think it would look like this,” he said.

His community, once home to 20 families, had grown to 70 by the time of the evacuation. “It was perfect for raising kids — between greenhouses, barns, fields and spacious homes,” he said.

Vilozny, like many others, never believed the disengagement would happen. “As kids, we didn’t really understand what was happening. Even when the army put up roadblocks, we thought it wasn’t real. We planned to resist, but when the soldiers arrived, we knew it was over. We left with a deep sense of betrayal.”

He eventually returned in uniform. “We always said the expulsion would hurt Israel’s security, but we didn’t imagine how much,” he said. “Now I’ve stood in Netzarim, a place I remember well. I may have been in uniform, but I felt like the 17-year-old boy running in the dunes. I believe we’ll return not only to fight — but to live there again.”

Shilo Biton, now in his late 20s, was seven when his family left Kfar Darom. Five years earlier, his father, Gabi Biton, had been killed in a terror attack. “We lived in a childhood paradise,” he said. “Yes, there was fear and tragedy, but also strong community life.”

On the day of the evacuation, the Biton family, along with other bereaved families and the town’s rabbi, were allowed to remain until evening to remove the Torah scroll from the synagogue in his father's memory. “We cried a lot,” Biton said. “We walked to my father’s memorial — it was like saying goodbye to him all over again.”

Biton was mobilized on October 7, 2023, following Hamas' deadly assault on Israeli communities. He entered Gaza on November 6, the anniversary of his father’s death. “It was a powerful closure. Emotional and frustrating — but filled with faith in our path. We believe we’ll return not just for war, but to live there again.”

Yehuda Bartov, who grew up in Neve Dekalim and now lives in Yad Binyamin, said his family never stopped hoping to return. “My parents still say that if new communities are built in Gaza, they’ll move there immediately,” he said. “We have sand from Gush Katif in the house and puzzles with photos from the Gush.”

Bartov remembered his grandmother shopping in nearby Khan Younis before the Oslo Accords changed the security situation. “A mortar once hit our house — but most memories are good ones,” he said.

He recalled feeling hopeful when he saw Israeli forces name routes inside Gaza after former settlements, like “Netzarim Road” and “Morag Road.” “It was moving to see that connection preserved,” he said.

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

During his military service, he discovered that the synagogue in Gadid was still intact. He sent photos to his family. “My grandparents recognized where they had lived. We immediately started talking about how to prepare to return. We believe it will happen.”

Israel’s 2005 disengagement from Gaza involved the evacuation of more than 8,000 Israelis from 21 settlements. The area was handed over to the Palestinian Authority before being seized by Hamas in 2007. Many evacuees resettled in southern Israel but continue to maintain strong emotional and ideological ties to their former homes.