As early as the 15th century, Rabbi Isaac Arama, one of the sharp Jewish thinkers of the late Middle Ages, identified this. In his interpretation of Pharaoh’s confrontation with Moses, he offers a surprising insight:

Pharaoh’s failure lies not in the data, not in understanding, and not even in sheer wickedness—but in his becoming locked into a single model of leadership, unable to challenge it even when reality is screaming otherwise.

In Arama’s words, the “hardening of the heart” is not an emotional punishment but a state of mind: a condition in which a leader continues to act according to a closed internal logic, even when he himself already sees that the price is steadily rising.

This is not only a religious insight. General philosophy identified the very same danger. Hegel described tragedy as a situation in which a party acts with complete logic—yet a logic that has lost touch with a changing reality. Thomas Kuhn called this a “paradigm”: a mental framework that explains the world brilliantly, until the moment it can no longer explain anything—yet continues to govern decisions.

In managerial terms, this is well known. An organization sees that the product isn’t taking off—and doubles down on investment. Customers are leaving—and procedures are tightened. Employees are burning out—and targets are raised. Each step makes sense on its own, but together they become a crash trajectory.

Here Rabbi Isaac Arama’s contribution is especially striking. He does not attack reason itself, but blind loyalty to it. According to him, there comes a stage at which leadership is no longer responding to reality, but defending its identity—its model, its story, its consistency.

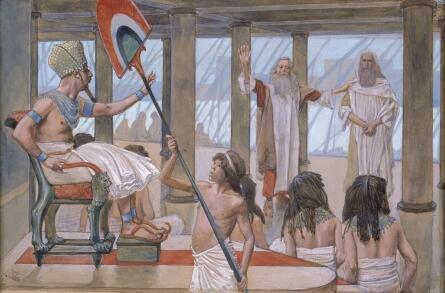

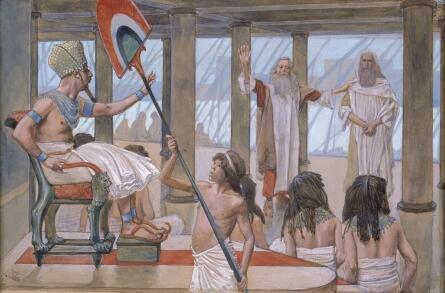

2 View gallery

Moses Speaks to Pharaoh by James Tissot at the Jewish Museum, New York

(Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Nietzsche, centuries later, argued that true strength is not measured by persistence, but by the ability to “break old tablets.” Kant himself warned against reason detached from life—reason that turns into a closed system. And the great managerial question is the same ancient one: when is persistence a strength, and when is it destructive stubbornness? Strong managers are not those who never make mistakes, but those who can recognize the moment when what must change is not just a decision, but an entire leadership conception.

I encountered such a situation with a decision by an American management team that was convinced an organizational structure had to be implemented immediately—one that ran counter to everything the environment was signaling. They could not be persuaded of their error, and the cost of the move was the loss of key members of the management team.

This week, Wix announced a return to five days a week in the office. In practice, the announcement generated employee frustration and dissatisfaction. Some companies are following the same trend, but after a long period in which the industry was persuaded that the hybrid work model is profitable and good for organizations, the impact is negative. In quite a few companies, we have seen employees leave for workplaces that allow at least one day of work from home. The real question is whether it makes sense to insist—or whether flexibility is possible, such as a model of five days in the office once every two weeks, and four days the following week, and so on.

There is a saying that stubbornness is an excellent trait—but like any trait, not in every case and not in every situation. Humility enables openness, which can lead to openness—and perhaps to a change of conception that may sometimes save the company.

Sometimes the greatest managerial courage is not to insist, but to stop and say: What once made sense is no longer right, and what worked no longer works. And those who fail to learn this in time discover that reason itself has become “a cage they believe is made of gold.”