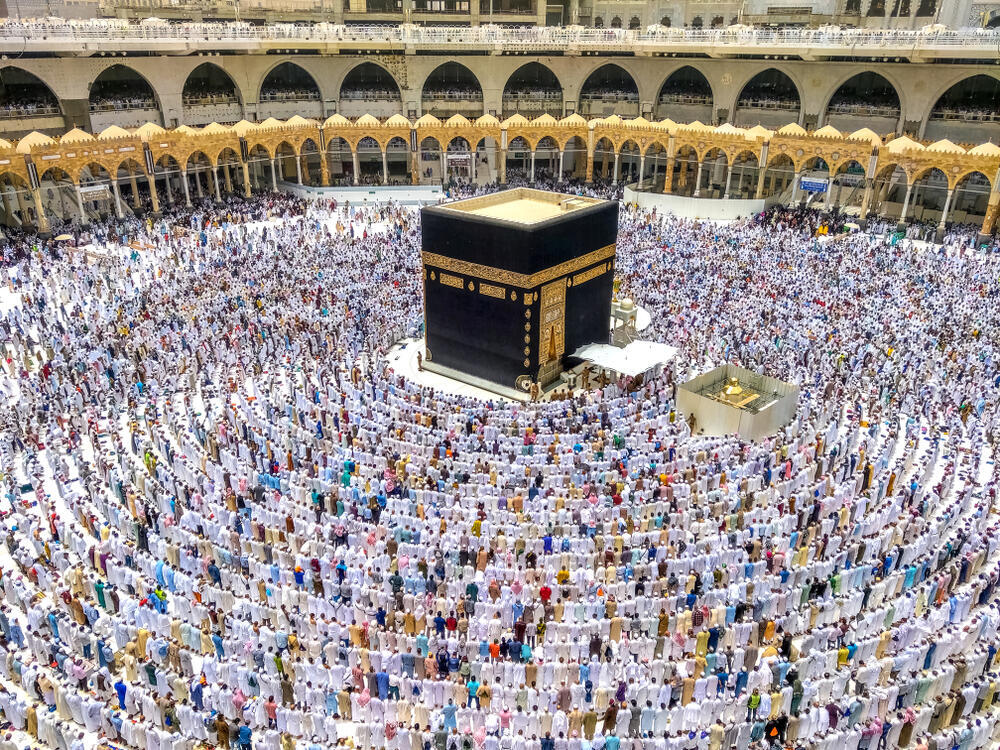

In 1979, Juhayman al-Otaybi seized the Grand Mosque in Mecca. He accused the House of Saud of corruption, Western alliance, and turning Islam into a display of images and materialism. He drowned the sanctuary in blood to stop what he saw as the Westernization of the Holy Land. His revolt shocked the kingdom—but also exposed a recurring fault line: when religion is alienated, radicalism rises.

Forty-five years later, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS) is repeating the experiment, only this time with golden cubes, neon lights and TikTok. The “Mukaab,” a massive Kaaba-like structure in Riyadh, dominates the New Murabba project, surrounded by desert raves, luxury hotels and Western pop concerts.

To the West, it is a symbol of modernization and economic ambition. To the underground Islamist networks, it is a provocation of biblical proportions. The argument that justified Juhayman’s attack is now alive—and digital. Al Saud, these radicals argue, has replaced divine law with glittering commerce.

The “New Kaaba” of capitalism

When the Mukaab’s design was unveiled, Saudi social media and diaspora networks exploded. Telegram channels, Signal groups, and expatriate media framed the structure as a temple to capital, not God. Every Riyadh Season concert, every Halloween party, every Nicki Minaj performance became a symbol of apostasy.

The remnants of the Sahwa—the Muslim Brotherhood-inspired “Awakening” movement—have adapted. They no longer preach from pulpits; they whisper in living rooms, schools and even bureaucratic offices. Every act of cultural liberalization is cataloged as proof that the House of Saud has abandoned religion. The message is clear: the golden idol in Riyadh validates Juhayman’s centuries-old critique.

The digital underground

Saudi Arabia’s Brotherhood networks have gone fully underground, evolving into a sophisticated, almost invisible insurgency. Cells (usrah) operate in encrypted apps, private Telegram channels and social media platforms. They share sermons, memes and viral videos, framing MBS as a tyrant who has betrayed the faith.

These networks are connected with diaspora groups in Qatar, Turkey and the West. Exiled clerics and ideologues provide funding, ideological guidance and digital amplification. Young bureaucrats, university students and professionals are quietly recruited, subtly taught to question state reforms and propagate dissent without drawing attention. Textbooks and educational materials are annotated, professional networks are leveraged, and social rituals are reframed as evidence of apostasy.

One viral TikTok juxtaposed Mecca’s green mountains with flashing lights at Riyadh Season, captioned: “You dance while God warns.” It spread across Saudi Arabia and the Gulf in hours, illustrating how a single clip now substitutes for a thousand pamphlets or sermons.

Signs of the end times

Nature itself is now a weapon in the Brotherhood’s narrative. Heavy rains in 2024–2025 transformed Mecca’s barren black mountains into lush green meadows. While the average observer sees climate change, the underground interprets it as Akhir al-Zaman. Eschatology, once the domain of distant clerics, is now viral. The Mahdi’s era is imminent, and MBS is cast as the tyrant ruling before the end.

The psychological effect is amplified by the Mukaab. A golden replica of Islam’s holiest site in the middle of Riyadh becomes the perfect counterpoint to divine signs in Mecca. The digital underground needs no rifles; viral images are enough to challenge legitimacy, inspire quiet resistance, and recruit followers.

The Sahwa goes dark—but not silent

Visible leadership has been purged. Clerics like Salman al-Ouda sit in prison. The religious police are gone. Yet the ideology persists, invisible but active. Brotherhood cells infiltrate universities, workplaces and public offices. Their methods are subtle, almost surgical: whisper campaigns, social-media campaigns, subtle curriculum influence and the nurturing of youth networks.

Every economic shortfall, cultural excess or mismanaged social reform is reframed as evidence of the regime’s apostasy. Online forums catalog these “offenses,” and diaspora support ensures they spread internationally, sustaining a narrative of divine punishment, Western corruption and inevitable collapse.

Historical echoes

MBS believes he can replace religion with money, nationalism and spectacle—the so-called “Grand Bargain” of 1979 rewritten. But history offers a warning. When Juhayman seized the mosque, it was a few hundred men with rifles; today, it is hundreds of thousands of followers in the shadows, connected digitally, embedded in institutions and ideologically armed. The narrative weapon is faster, more lethal, and harder to contain.

The kingdom’s leadership faces a paradox: modernize too fast and risk alienating religious conservatives; move too slow and the economy and youth will rebel. Every flashy concert, every new Western icon, every Mukaab photo fuels the underground narrative. The social contract is fraying.

A dangerous gamble

Western powers have invested heavily in the idea that MBS has tamed Wahhabism. This is a dangerous illusion. By dismantling the social compact of 1979, MBS is betting that money and spectacle can replace centuries of religious authority. Yet NEOM’s ambitions are scaling back, unemployment persists, and youth remain restless.

Juhayman had rifles; today’s insurgents have narratives. They are invisible, embedded and viral. They whisper in homes, post online and educate quietly, all while MBS pursues the gleam of gold in Riyadh. If the economy falters or the spectacle fades, what remains is anger—and the digital ghost of 1979.

The West must not mistake silence for acceptance. Radicalism in Saudi Arabia has evolved: it no longer storms mosques, it whispers, posts, and videos. And it waits.

Amine Ayoub, a fellow at the Middle East Forum, is a policy analyst and writer based in Morocco. Follow him on X: @amineayoubx