It is too early to eulogize Iran’s ayatollah regime, and difficult to overstate the immense damage it has inflicted on its own people and on global stability. It is also hard to find a corner of the world untouched by this regime’s reach and its network of proxy organizations. Wherever it has extended its influence, it has established outposts of terror and chaos.

Since the 1979 Khomeini revolution, the ayatollah regime has built a deeply entrenched internal power structure in Iran, primarily through the Revolutionary Guards and the Basij, which have brutally and effectively suppressed every wave of protest to date. Overthrowing such a regime, fortified internally and shielded externally by its proxies, is a complex and challenging task. It is therefore no coincidence that global discourse has largely avoided serious discussion of the “day after” in Iran.

From a broader perspective, the ability of this regime, and others like it, to operate and expand has not occurred in a vacuum. It is the product of the global balance of power and the question of hegemony at any given time. To a large extent, though not exclusively, the rise of Iran, alongside China and Russia, reflects the strength or weakness of American leadership.

World history, shaped by struggles between empires and great powers, shows that global stability is achieved when a single dominant power holds a clear advantage over its rivals. This was the case during the Pax Romana from 27 B.C. to 180 A.D., when Roman military and economic supremacy ensured stability across the Mediterranean. It was also true after World War II during the period known as Pax Americana, when clear American hegemony reduced global conflict and created relative stability.

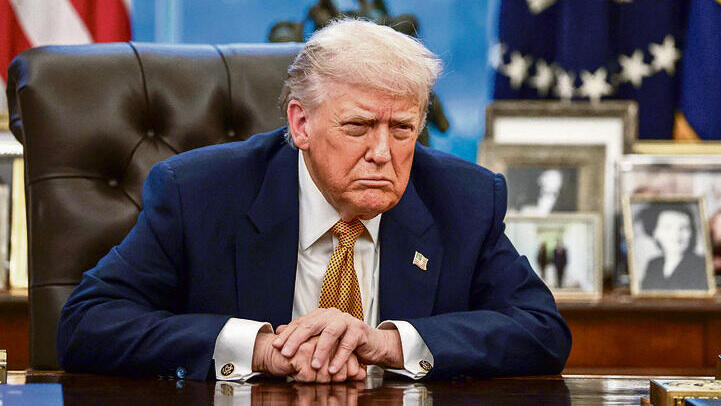

In seeking to restore American power, U.S. President Donald Trump has identified forces that threaten U.S. hegemony, led by China, already an economic superpower with the potential to become a military threat. On the global chessboard, his administration has worked to remove actors aligned with Beijing while forming counter-alliances.

Trump’s actions must be understood in this context. The capture of Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro, strikes on Iranian nuclear facilities, and even Trump’s interest in Greenland are not impulsive moves driven by presidential whim. They represent a determined effort to reassert American dominance, regain control over key economic power centers, topple hostile regimes and impose economic pressure on others.

The nuclear deal as a case study

Over recent decades, U.S. policy on the use of force has fluctuated sharply. The conciliatory and isolationist approaches of the Obama and Biden administrations contributed significantly to the rise of China, Russia and Iran. Attempts to normalize relations with a murderous regime openly committed to Israel’s destruction through the nuclear deal are a prime example.

The misguided belief, shared by those administrations and their European partners, that Iran’s ambitions could be restrained only incentivized continued development of weapons of mass destruction.

The same misunderstanding of reality appeared elsewhere. During the Arab Spring, President Barack Obama abandoned longtime ally Hosni Mubarak, assuming that protests calling for democracy would end accordingly. The result was the rise of the Muslim Brotherhood under Mohamed Morsi. The same administration drew red lines in Syria but failed to enforce them, even after Bashar Assad used chemical weapons against his own people.

President Joe Biden likewise sought engagement with Iran, attempting to create a balanced Middle East that would produce a semblance of calm.

By contrast, Republican administrations under Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush and George W. Bush acted more decisively to position the United States as the world’s leading power and did not shy away from weakening or toppling hostile regimes. Reagan and Bush Sr. helped bring about the collapse of the Soviet bloc, while Bush Jr. oversaw the removal of Saddam Hussein.

Planning for the day after

Creating a new global balance of power is a long and often violent process, as current events demonstrate. The removal of Maduro may be inelegant and possibly challenge international law, but it is a step toward dismantling a hub of terror and narcotics that controls vast oil reserves. Toppling Iran’s regime is a necessary step toward stabilizing the Middle East and creating an economic corridor from India through Israel to Europe.

In the time since Operation Rising Lion, the US administration has reached the inevitable conclusion that damaging Iran’s nuclear capabilities alone will not change its intentions, only delay them. Yet discussion of Iran’s future has been almost entirely absent from public discourse.

There is broad agreement that an alternative to the current Iranian regime must be created, whether led by the shah’s son in exile or another local figure. But even if the regime falls, Iran will face a difficult transitional period before new leadership emerges. As a state composed of multiple ethnic groups and tribes, Iran could descend into chaos, and some groups may seek autonomy.

Only after the complete collapse of the current regime can alternative forces emerge. This lesson should also be applied to Gaza. Violent regimes such as Hamas do not allow any governing alternative to develop until they are removed.

Claims by some Israeli public figures that Israel should have prepared for the “day after” in Gaza while waging a total war against Hamas ignore the reality that no viable alternative can be formed while such a regime remains in power.

Evil must be eradicated. Replacing Hamas with the Palestinian Authority as a so-called necessary evil is akin to replacing Iran’s ayatollah regime with another jihadist group.