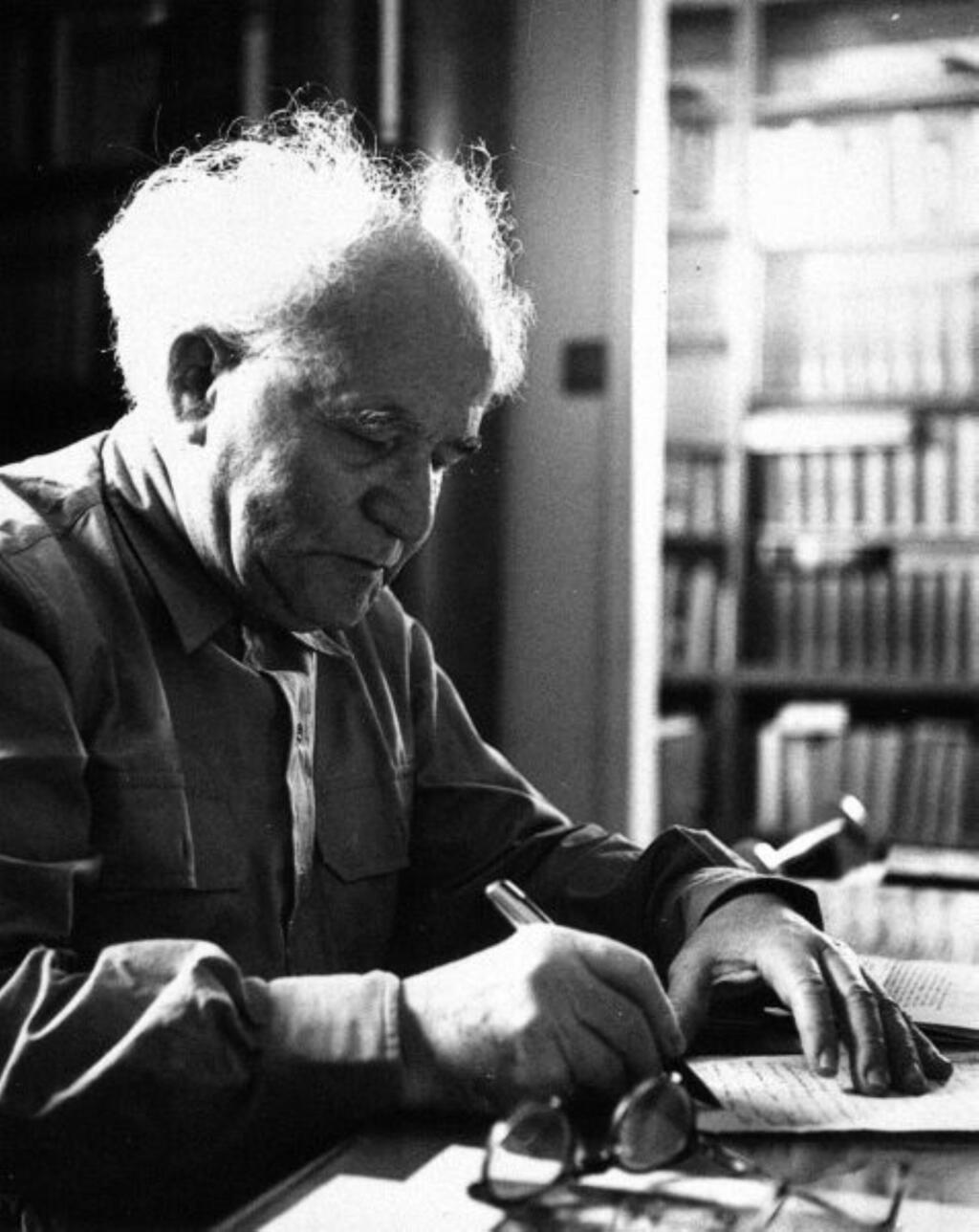

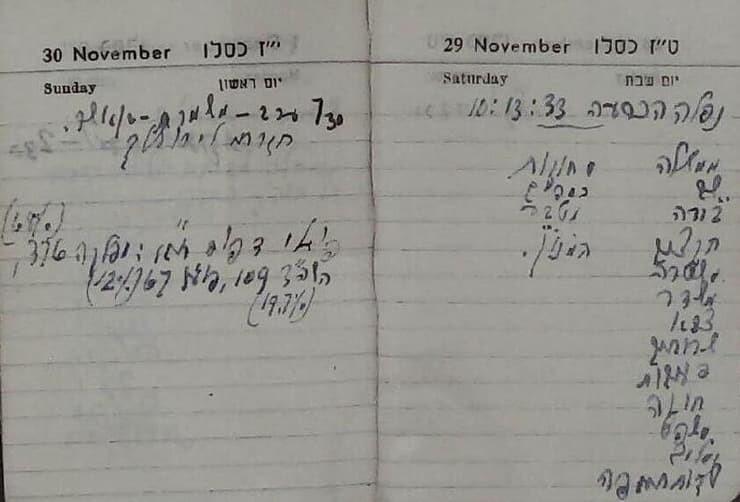

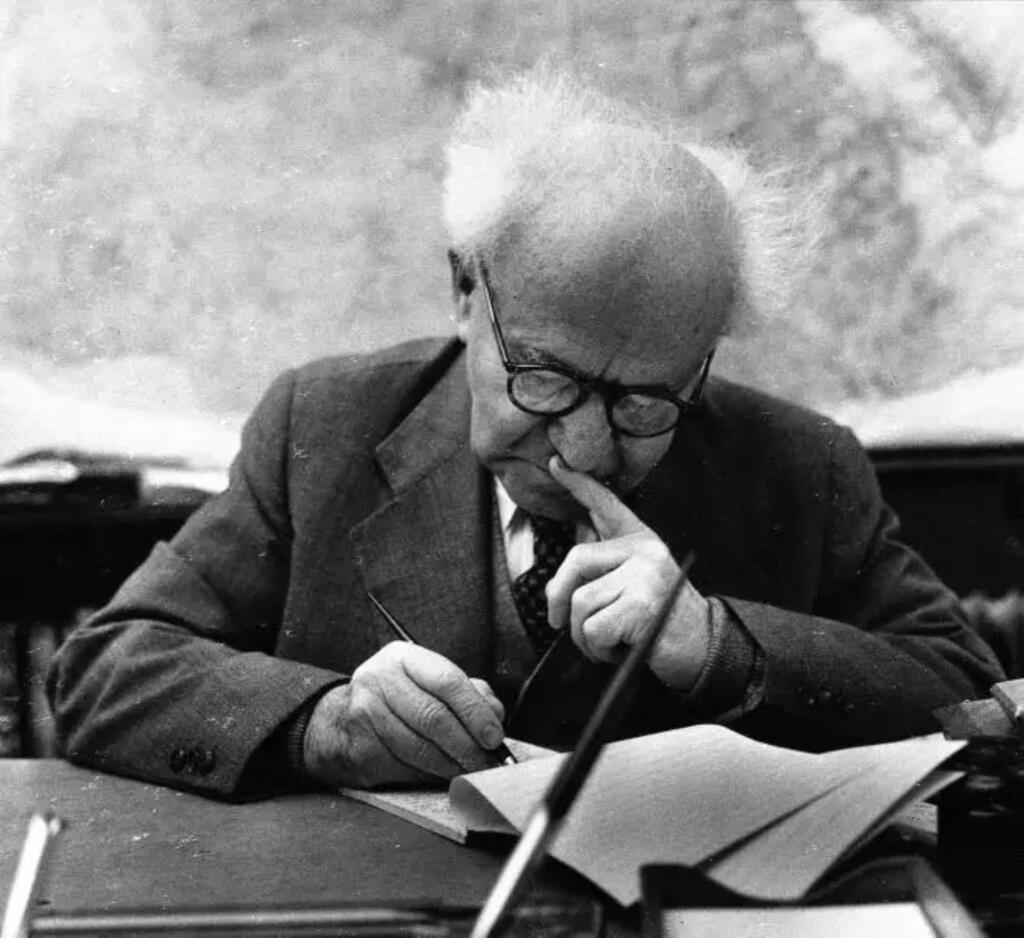

On November 29, 1947, as the UN voted on their Partition Plan for the Land of Israel, David Ben-Gurion was sat in a hotel in Kalia, by the Dead Sea. Listening to the radio, he recorded the results in his pocket diary: "The verdict was rendered - 10:13:33".

The required two-thirds majority was met; there would be a Jewish state in the Land of Israel alongside an Arab state.

In Kalia and across Israel, people danced on the streets, but Ben-Gurion, leader of the Zionist movement, couldn't celebrate.

How does one build a state? How could he turn a movement into a sovereign nation?

Ben-Gurion returned to his diary and listed the building blocks of a state: "Government, name, capital city, budget, police, broadcaster, army, public services…."

The foundations had been built over decades, but facing the prospect of becoming a sovereign, independent nation, Ben-Gurion had to think about the concept of a state from scratch.

The challenges facing the nascent State of Israel were numerous and foreboding: developing state institutions; settling the land; and absorbing waves of new immigrants – many of whom arrived penniless, survivors of the Holocaust or expelled from their home countries - all while fighting an existential war.

One more challenge preoccupied Ben-Gurion. He would lead a Jewish state, the citizens were committed to parties and movements, not to the country as a whole. There were socialists, communists, liberals and revisionists. Religious, secular and Haredi Jews. The 'Old Yishuv', pre-state pioneers and new immigrants. Ashkenazim and Mizrahim, Zionists and non-Zionists. Neither were the citizens only Jews - there was a substantial Arab minority. Founding a state requires citizens who feel they are part of a state, not just a political party, who follow its laws and to help design and build its future. How could he weave together these disparate threads into a national tapestry?

Ben-Gurion's answer was a new governing philosophy: Mamlakhtiyut. Variously translated as republicanism, statesmanship or national unity, it no real English equivalent because Mamlakhtiyut is unique to Israel, arising from its exceptional situation in 1948.

Mamlakhtiyut envisions a two-way relationship between the state and its citizens. The citizen must accept the authority of the institutions of the state and its elected leaders; the state takes responsibility for all its citizens equally. The citizen's loyalty to the common good takes precedence over loyalty to sectoral, partisan or communal interests. The mamlakhti state is led and built by active, engaged citizens.

Implementing this vision was far from easy. Mamlakhtiyut meant dismantling the pre-state partisan militias, at the height of the War of Independence, because Israel could only win a war with a mamlakhti military that fully accepted the authority of the state and its leadership.

In place of each political movement running their own schools, Ben-Gurion imagined a mamlakhti education system. The new generation would see themselves as sovereign citizens, committed to the state and to building the state. Here he had a partial victory[עמ7.1]– most schools were split between Mamlakhti, and Religious Mamlakhti streams, although some Haredi institutions remained independent.

Mamlakhtiyut infused nearly every speech Ben-Gurion made and elevated the most banal legislation into a call for civic responsibility. Proposing regulations for the new civil service in 1953, Ben-Gurion imagined the most junior state employee as the bedrock upholding the nation.

"More than any other state, the State of Israel is dependent on spirit and desire pulsing through the nation in its entirety, on the willingness of every one of her citizens to fulfil their duty to all, on a sense of mamlakhti responsibility in every resident," he said in sharing his vision.

The struggle to underpin the new state with Mamlakhtiyut was not without opposition nor mistakes. But Ben-Gurion believed that without the mamlakhti consensus forged in Israel's early years, it could not have won the War of Independence, absorbed millions of new immigrants or settled the Negev and the Galilee.

Today, Israel is not starting from scratch but faces significant challenges all the same. I won't guess what Ben-Gurion would say if he saw Israel today - the world he inhabited was very different. But his philosophy remains relevant and urgent. Mamlakhtiyut isn't simply a cry for unity. It demands a state responsible for all its citizens equally and engaged citizens who accept the authority of all the state's laws and institutions and feel a civic responsibility to better the society in which they live.

Ben-Gurion's question from November 1947 is just as relevant now.

How does one build a state? 'One' doesn't build a state – many do.

Mamlakhtiyut asks the state and its citizens to work in partnership, look up from day-to-day political fights and imagine a better, more secure and more prosperous future for the country in its entirety.