A nurse carries a smiling young girl in her arms. Behind her walk other women, all looking directly at the camera. Barbed wire fences flank both sides of the image. The photograph is in black and white, the composition strikingly symmetrical and meticulously framed, taken from a slightly elevated vantage point. Except the scene never happened.

We know many photographs and video clips from Auschwitz in which emaciated, exhausted prisoners stare directly into the lenses of Soviet army photographers. In the Auschwitz Album, shot by SS personnel in 1944, Jewish women from Hungary are seen arriving at the camp. In a short film recorded days after liberation, Soviet nurses escort a group of children between barbed wire fences, children who survived, almost miraculously, the brutal medical experiments of Josef Mengele.

5 View gallery

An image shared online. The story is real, the image is fake

(Photo: Facebook page - Threads of Time)

And yet the image of the nurse carrying the smiling girl continues to spread across social media. I encountered it on Facebook. It is no coincidence that it evokes associations with Auschwitz. It condenses into one “perfect” image a series of familiar visual symbols from the concentration and extermination camps. That alone should raise suspicion.

The caption attached to one of the posts, published on January 17 on a page called “Threads of Time,” is even more confusing. According to the text, the scene depicts Ravensbrück concentration camp and tells the story of a Polish nurse named Elzbieta Kowalska, who was forced to join a death march with other prisoners as Soviet forces approached. But the details do not add up. Why are the women looking so confidently into the camera? Why is the nurse presented as such a theatrical heroine, and through the lens of a Nazi photographer? And why does the landscape bear no resemblance to the known topography of the women’s camp north of Berlin?

Beyond repeated posts telling the same story, almost no verifiable information exists about this nurse. Some publications include additional images, one even showing her name embroidered on a nurse’s uniform, yet her face appears entirely different.

What can be verified is that very few photographs from Ravensbrück have survived. Only 92 images appear in an SS album from 1940 to 1941, and they depict a completely different environment. The few photographs taken immediately after liberation also show another reality. The hyper-realistic quality of the viral image, its near-perfect composition and its way of summarizing familiar camp symbols, combined with multiple similar posts from the same account, strongly suggest that it was generated by artificial intelligence.

5 View gallery

Survivors of the Auschwitz concentration and extermination camp pass through its gates after liberation, February 1945

(Photo: imago images/Reinhard Schultz/Reuters)

In recent years, AI-generated Holocaust images have flooded social media. “Fake history,” as Auschwitz Museum spokesman Pawel Sawicki has called it. The phenomenon is particularly widespread on platforms owned by Meta. Estimates suggest that about 40 percent of content distributed on Facebook is AI-generated, yet only a tiny fraction is labeled as such, despite platform rules.

Sawicki warns that photorealistic images like these pose “a new danger of distorting the history of Auschwitz,” because photography has long been perceived as a documentary medium, evidence of a real photographer’s presence at a specific time and place.

Similar concerns were raised by Michaela Kuechler, secretary-general of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, at a recent Berlin event of the SHOAH STORIES education project. She noted that AI-generated content is often shared without context, and that most users are unable to identify it as fake. This is particularly troubling because the digital sphere has fundamentally changed how people encounter Holocaust history.

Against this backdrop, more than 30 memorial sites, foundations and initiatives in Germany published an open letter ahead of International Holocaust Remembrance Day, calling on platform operators to act more decisively. Their demands include clear labeling of AI-generated content, removal of such material and more effective tools for reporting visual forgeries. Posts like those described here undermine the work of commemorative institutions because they often draw on real names and events while encouraging memory based on immediate emotion and visual manipulation rather than learning and understanding.

As Konstantin Snelder of the Center for Responsible Digitality notes, such deepfakes increasingly shape how we perceive the past. When historical information is consumed casually on platforms like Facebook, Instagram or TikTok, there is a real risk that fake images will embed themselves in visual memory without scrutiny or critique. This heightens the importance of AI literacy alongside broader digital literacy.

New challenges for historians

AI-generated Holocaust images also pose challenges for archives themselves. In recent years, researchers have intensified efforts to trace the origins of the few films and photographs we have from the Holocaust. Historians Tal Bruttmann, Stefan Hördler and Christoph Kreutzmüller have carefully analyzed and contextualized the Auschwitz Album.

5 View gallery

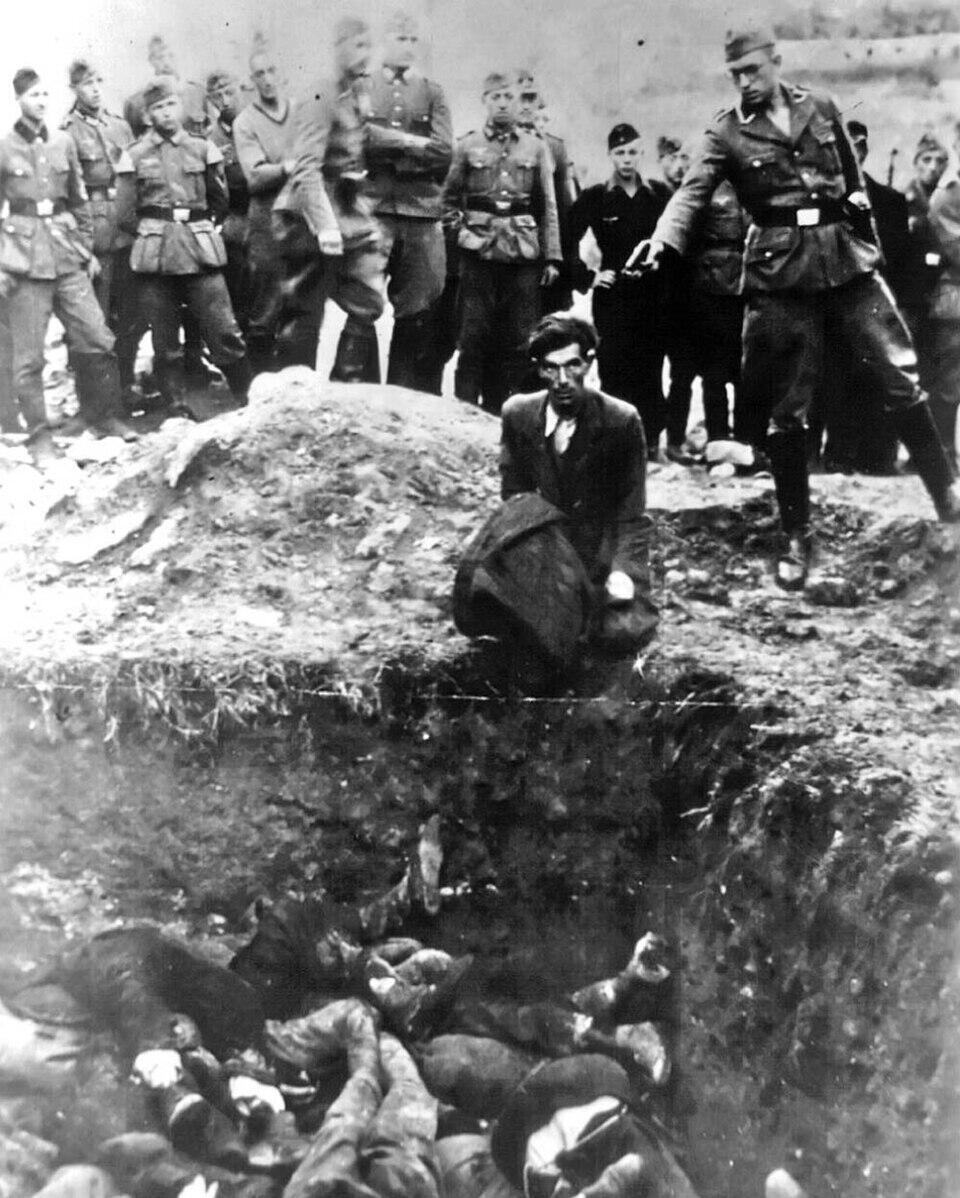

'The Last Jew in Vinnitsa.' The iconic photograph may in fact have been taken in Berdychiv

At the Hebrew University, a German-Israeli research project is reexamining well-known cinematic images from the Nazi era, where they were shot, under what circumstances and how they have been used over time. The project examines footage from pogroms in Riga and Lviv, mass shootings in Latvia and boycotts of Jewish businesses in Germany.

Last year, historian Jürgen Matthäus clarified the background of the iconic photograph known as “The Last Jew of Vinnitsa,” showing that the execution documented took place on July 28, 1941, and identifying the location as the Berdychiv fortress in what is now Ukraine. He also used analytical AI, which helps identify patterns and connections in data. Unlike generative AI, which synthesizes old material into something new, analytical AI can assist in linking data, identifying objects or people in historical images, or analyzing camera angles, movements and compositions, as in the joint European project Visual History of the Holocaust.

Media scholar Roland Meyer notes that artificial image creation does not truly create images but synthesizes existing material. It does not operate through empirical investigation but through statistical probability. The result is an amplification of visual clichés, a “cliché amplifier” that produces symmetrical, polished images.

This is why images like the one described at the beginning appear so symmetrical. They lack the imperfections, randomness and even propagandistic staging that characterize so many authentic Holocaust photographs. What historians call the “perpetrator’s perspective,” evident in many Nazi images and films, simply cannot be generated by AI. Instead, these images reveal the prompt behind them, visualizations of generic descriptions. Meyer therefore calls this effect a “generic past.”

The flood of such synthetic images raises concerns that visual archives themselves may undergo a process of blurring and contamination, in which fake images gradually become historical reference points.

Filmmaker Claude Lanzmann once referred to historical photographs of Nazi crimes as “images without imagination.” That description applies even more to photorealistic images generated by artificial intelligence. They do not unsettle or disturb. They operate emotionally only because they confirm what viewers already expect to see. These are artificial visual symbols that contribute to the erosion of historical truth.

For that reason, responsibility also lies with users themselves. Beneath the fake image of the “Polish nurse” from Ravensbrück, a simple comment recently appeared: “True story. Completely fake AI image.”

Tobias Ebbrecht-Hartmann is an associate professor in the Department of Communication and Journalism and the European Forum at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. He is a partner in the EU-funded research consortium ‘Visual History of the Holocaust: Rethinking Curation in the Digital Age’ and the Israeli partner in the German-Israeli project ‘Images with Consequences.’