For forty years, the view from Jerusalem has been dominated by a single silhouette: the “Turban.” This symbol embodied the grim, ideologically rigid occupation imposed by Iran’s ayatollahs and their local contractor, Hezbollah. It was a predictable enemy, one that spoke the language of martyrdom, turned South Lebanon’s villages into missile silos, and ran an economy of “resistance” fueled by cash-stuffed suitcases rather than credit ratings.

But as the smoke clears from the latest conflict and the rubble settles in a post-Assad Syria, the region is undergoing a tectonic shift that demands an immediate update to the strategic threat matrix. Hezbollah’s grip is weakening. Its Syrian lifeline has been severed. Yet nature and geopolitics both abhor a vacuum. As the Turban recedes, a new, arguably more insidious threat is emerging from the shadows of the Levant.

This new occupier does not chant “Death to America” or burn flags at the airport. It wears a tailored business suit. It speaks the smooth language of “regional stability” and “Sunni protection.” It arrives bearing construction contracts funded by Doha and backed by the NATO-trained muscle of Ankara.

While the West and Israel celebrate the weakening of the Iranian axis, Lebanon is walking blindfolded into a trap: trading the Shia Islamist prison of Iran for the Sunni Islamist cage of the Muslim Brotherhood. The danger for Israel is that while it marks the defeat of the proxy, it may be missing the arrival of the empire.

The first shot of this new occupation was not fired from a Katyusha rocket, but delivered through a diplomatic veto that should send a chill through Western capitals. On December 16, diplomatic channels buzzed with reports of a sharp rebuke from Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan to Lebanese Prime Minister Nawaf Salam. The trigger was Lebanese President Joseph Aoun’s courageous move to operationalize a maritime demarcation agreement with Cyprus.

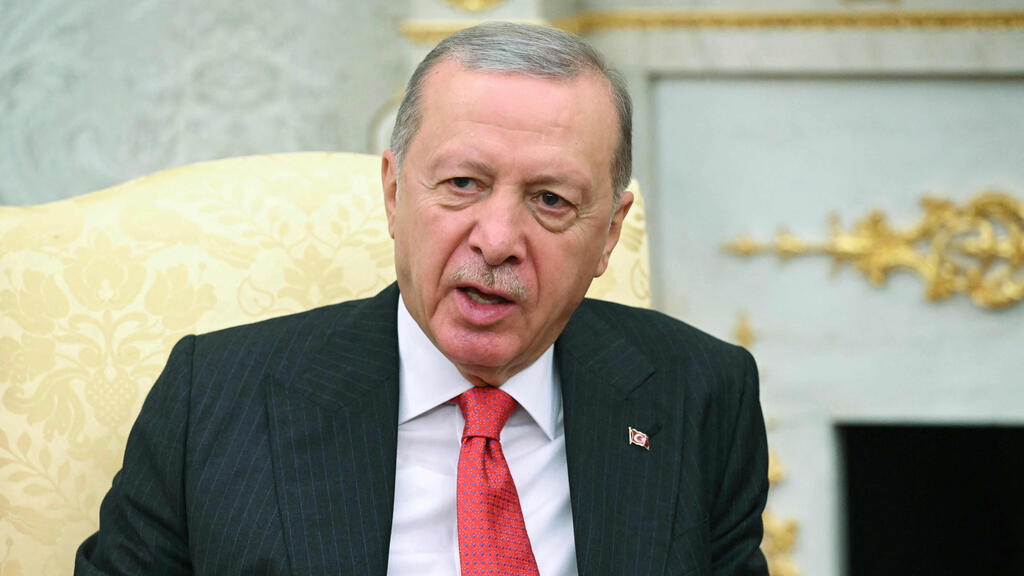

Ankara’s message was chillingly clear: Lebanon does not have the right to define its own borders without Turkish approval. Under President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s “Blue Homeland” doctrine, the Eastern Mediterranean is treated not as an international waterway, but as a neo-Ottoman lake. Turkey has little interest in a sovereign, prosperous Lebanon. It seeks a satellite state, a southern flank that blocks the emerging energy alliance linking Israel, Cyprus and Greece.

This danger is magnified by seismic shifts next door. The fall of the Assad regime and the rise of a transitional government led by Ahmad al-Sharaa, formerly the jihadist Abu Mohammad al-Jolani, have electrified the Sunni street in Tripoli and Beirut. There is palpable euphoria, a sense that the “Shia Crescent” has finally been broken.

But analysts warn this is a dangerous illusion. Al-Sharaa represents a joint venture of the Turkey-Qatar axis. If Lebanon pivots from Tehran to Ankara in a desperate search for “Sunni balance,” it will merely exchange one form of Islamist authoritarianism for another. The warning signs are already visible, as Turkish intelligence expands its footprint in northern Lebanon and groups such as the Fajr Forces drift back toward their ideological roots, creating a new, multi-headed threat along Israel’s northern border.

There is, however, a third option.

It is the path the ideologues of “resistance” fear most, and one that courageous Lebanese leaders are beginning to whisper about openly. It is the path of the Mediterranean.

The appointment of Simon Karam, a civilian former ambassador and outspoken critic of both Syrian and Iranian domination, to lead the ceasefire monitoring delegation with Israel was a revolutionary signal. It suggested that the Lebanese state may finally be prepared to treat border security as a diplomatic challenge rather than an eternal religious war.

Amine Ayoub

Amine AyoubThis is the “Western prosperity” track, and it relies on assets deliberately neglected by the axis of resistance.

Imagine a Lebanon integrated into the Western economic framework, where the dormant Rene Mouawad Airport in the north becomes a bustling low-cost hub with direct links to Europe, breaking Hezbollah’s stranglehold on Beirut’s main airport. Imagine a country that stops waiting for Iranian fuel tankers and instead connects to the EuroAsia Interconnector, physically linking its power grid to Cyprus and Israel and ending blackouts overnight.

Now envision the restoration of a trade corridor linking Haifa to Tripoli, integrating Lebanon directly into the global economy while bypassing the chaos of Syria altogether.

This is the Mediterranean option.

A peace that pays.