A few months ago, outgoing New York City Mayor Eric Adams hosted several hundred members of the Jewish community at Gracie Mansion, his official residence, to mark Jewish American Heritage Month. It was an oppressively hot and humid day.

The lawn overlooking the East River looked like a postcard, but the air was heavy. The kosher wine was too sweet, the hot dogs ran out before most guests reached the stand, and many attendees clustered in the shade, waving napkins and quietly grumbling. Still, amid the sweat, portable fans and white-clothed tables, one phrase echoed over and over: Cherish the moment, this might be the last time we’re here.

On January 1, a new tenant will move into the mansion. Unlike his predecessor, it’s doubtful Zohran Mamdani will become a favorite of the Jewish community. It's unclear whether he will host Jewish events or uphold the traditions of previous mayors. But one thing is certain: the mezuzah at the main entrance, installed in the 1970s by Jewish Mayor Abraham Beame, will stay right where it is.

The Mamdani family may not kiss it daily, but city preservation laws prohibit mayors from making any changes to the mansion’s first floor, which is reserved for official functions. The front door will remain yellowish, the chandeliers will continue to sparkle, and the walls will still tell their stories.

Mamdani, 34, and his new wife, Syrian-American artist Rama Duwaji, 28, still live in a modest one-bedroom apartment in Astoria. Just days before his election, he dealt with a plumbing issue in the unit, laying towels on the aging parquet floors to block water seeping from the sink.

He later admitted to reporters that the apartment was too small for him and his partner. The contrast between that reality and the grandeur awaiting him, should he choose to live in the so-called “Little White House” visible from his apartment across the river, is almost unimaginable.

Michael Bloomberg spent $7 million on renovations, but never lived there

Gracie Mansion spans about 11,000 square feet. It has five bedrooms, a ballroom, a sprawling lawn, rows of apple and fig trees, a vegetable garden with roaming rabbits, and a full-time chef serving residents and their guests. Most mayors eventually move in, even if they initially prefer their own homes. Security demands often decide for them. Some quickly adjust to the luxury and space; others complain that it isolates them from the daily life of New Yorkers.

Ed Koch, the legendary Jewish mayor who served three terms, refused to leave his rent-controlled Greenwich Village apartment. But after a flood of phone calls from residents, as he had forgotten to unlist his home number after taking office, he gave in and moved to Gracie Mansion. “I said you can get used to posh very quickly,” he lamented after losing the 1989 election: “And I got used to it.”

Michael Bloomberg, by contrast, never lived in the mansion. He remained in his private, more opulent townhouse on 79th Street, just a short drive away. Still, he invested more in the mansion than any other mayor, spending about $7 million of his own money to restore the building, including repainting the walls, doors and frames in their original colors.

Eric Adams rarely stayed there, claiming the mansion was haunted by ghosts. Chirlane McCray, ex-wife of former Mayor Bill de Blasio, also reported hearing doors open and close on their own, as well as whispers believed to be from the daughter of Archibald Gracie, the home’s original owner.

9 View gallery

Mamdani, and his new wife, Rama Duwaji. Will they move in?

(Photo: REUTERS/Jeenah Moon)

Mamdani, who ran on a socialist platform with promises of housing reform, has yet to commit to moving in. The gap between Astoria and the Upper East Side isn’t just about real estate. Astoria is young and multicultural, with halal street food and Egyptian, Greek and Thai restaurants that Mamdani especially enjoys.

In one campaign video, he posed with a plate of knafeh nabulsi, under $10 in Astoria, while speaking Arabic. On the Upper East Side, if it’s available at all, the same dessert could cost nearly three times as much.

The couple won’t just be switching apartments; they’ll be moving between two entirely different urban realities, between dense, lived-in streets and a quasi-suburban estate. Between a walk-up with a shared laundry room and a stately country-style residence adorned with historic tapestries and custom silverware.

To understand what awaits there, you have to look at the house itself. Gracie Mansion was built in 1799 as a summer retreat outside the city for Archibald Gracie, a wealthy New York merchant. He bought the remote land after a previous house on the site was destroyed during a battle in the American Revolutionary War.

To this day, the estate contains remnants of a basement and a secret tunnel leading to the river, possibly an escape route during wartime. Some theories suggest it was used for smuggling secret guests or mistresses. A cannonball, believed to date back to the 1776 battle, still rests on a shelf in the Yellow Room.

Although it was far from the bustle of the city, which at the time was centered around the Lower East Side, Gracie viewed the location as advantageous: clean air, distance from growing urban density, and access via ferry from the port.

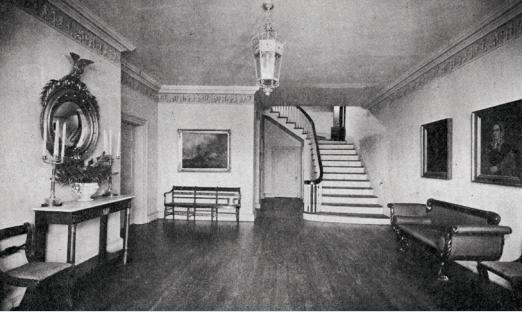

He expanded and renovated the home multiple times. Its wide porches, built in the Federal architectural style and facing Hell Gate - a narrow and dangerous tidal strait in the East River - and its grand library made it a hub for the political, economic and literary elite of the time. Regular visitors included President John Quincy Adams, the first U.S. Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton, real estate mogul John Jacob Astor, Irish poet Thomas Moore and Louis-Philippe, who would later become King of France.

A documented 1801 salon gathering notes that funds were raised there for the founding of what would become the New York Post. Washington Irving wrote parts of Astoria at the mansion, describing it as a refuge of clear air and deep quiet.

But history also has darker chapters. While slavery in New York was then on a path of “gradual abolition,” many Black laborers who built and maintained the estate and gardens were labeled as “contract workers,” a term used to hide evidence of labor exploitation.

The mansion was nearly demolished

After suffering financial ruin following the War of 1812, Gracie sold the house to Joseph Foulke, a merchant whose wealth stemmed largely from colonial holdings in the Caribbean and enslaved labor. He was followed by contractor Noah Wheaton, during whose tenure the house began to crumble.

When Wheaton died without paying his taxes, the city’s Parks Department took over the property, inheriting a dilapidated and purposeless building. For decades, the city wasn’t sure what to do with Gracie Mansion. It stood neglected, a shadow of its former self. At various times, it served as pay-per-use public restrooms (for five cents), a storage facility, a classroom, and even an ice cream stand. Photos from that era are difficult to look at: broken windows, overgrown vegetation, a house lost to time.

During the 1920s and 1930s, there was mounting pressure to tear the mansion down and replace it with open parkland. The mansion was ultimately saved thanks to a group of affluent neighborhood women who rallied to preserve it as a “symbol of old New York.” They convinced the city to convert it into a museum on early 19th-century city life. Items and furniture were donated by old New York families, while others came from museums and private collections.

In 1942, following the attack on Pearl Harbor, Mayor Fiorello La Guardia was persuaded to move into the house, accompanied by a full security detail, during the war. Since then, Gracie Mansion has become known as the “Little White House” and has served as the official residence of (nearly) every mayor since. Some tried to make it feel like home. Others focused on preserving its history. More than a few tried to leave as quickly as possible.

A new wing was added in 1966 after the wife of then-Mayor Robert Wagner Jr. complained that the house was too small for hosting. Guests moving between floors often wandered into the family’s private quarters; some even left with ashtrays, pipes, lipstick or jewelry as souvenirs.

The expansion created a clear division between formal entertaining and family life, similar to the layout of the White House. It was funded by private donations and sparked public debate: Should the mayor live modestly or in a setting befitting a head of city government?

Gracie has undergone several major renovations since, mostly funded privately rather than through the city budget. Mayor John Lindsay and his wife, Mary Anne, put in long hours to fix water-rotted windows, uneven floors and cigarette-burned carpets, once complaining that their bedroom door frequently got stuck, forcing them to climb out the window and reenter through another.

One of the most extensive renovations came in the early 1980s under Mayor Ed Koch at a then-staggering cost of about $5.5 million. The entry floor was restored to its original black-and-white tiled design but painted by hand to resemble marble. Koch later said that it would have been cheaper to just use real marble.

Over the years, small traditions developed. Several windows in the home bear etched signatures from mayors’ children, a kind of rite of passage. The first was Emily Quackenbush, granddaughter of owner Noah Wheaton, who carved her name with a diamond in 1893. Later, the daughters of Mayors Lindsay, Giuliani, Bloomberg and de Blasio followed suit.

Mayor Bill de Blasio, for his part, accepted a $65,000 furniture donation from West Elm, citing the private living quarters’ furnishings as unsuitable for daily use. He replaced beds, dressers and carpets in the family wing, while the historic pieces were moved to preservation storage. The public reception areas remained untouched.

Giuliani moved in with his wife, Donna Hanover, and their children in 1994. When the marriage fell apart, he announced the separation in a press conference, before telling his family. Hanover sought a court order to limit his access to the mansion. Giuliani left and didn’t return for several months, only doing so after reaching a temporary legal agreement.

Under Eric Adams, the mansion was mostly used for high-profile events like New York Fashion Week. Adams, as noted, rarely slept there, preferring his Brooklyn condo. His son, rapper Jordan Coleman, however, held several Instagram-worthy parties at the mansion, which drew mixed reactions.

One night, while the house was empty, a man climbed the fence, entered the grounds, and stole the Christmas wreath hanging at the entrance. He was quickly apprehended nearby by police and charged with theft and trespassing. The local press used the incident to criticize the mayor for leaving an expensive official residence underused and paid for by taxpayers.

If Mamdani moves in, the upper floors will be his. He could bring in his own furniture, convert bedrooms into offices, and choose to dine either in the private dining room or the formal banquet hall with the mansion’s chef. But the main floor, used to receive guests, will remain nearly untouched.

Monday-only public tours (by reservation and for a $10 fee through the official website) show visitors a home that feels like a set from another century.

What will become of the mansion’s traditions - Jewish, Arab, Afro-Caribbean and others? It’s too early to say. Each mayor brings their own tastes and community. But the mezuzah on the yellow front door of the main floor will remain - when Mamdani moves in, and long after he leaves.