For years, historians believed a devastating plague led to the abrupt abandonment of Akhetaten, the short-lived capital of ancient Egypt. But new archaeological research suggests the epidemic never occurred, rewriting a key chapter in Egypt’s history. A study by Dr. Gretchen Dabbs of Southern Illinois University and Dr. Anna Stevens of Monash University, published in the American Journal of Archaeology and reported by Phys.org, found no evidence of a mass-death event in the city.

Akhetaten, modern-day Amarna, was built by Pharaoh Akhenaten, formerly Amenhotep IV, of Egypt’s 18th Dynasty. Known for his radical religious reforms, Akhenaten elevated the sun god Aten above all others, abandoning the traditional worship of Amun. Seeking to distance himself from old religious centers, he founded a new royal capital called Akhetaten, “the horizon of Aten.” The city thrived for only about two decades before being abandoned shortly after Akhenaten’s death in 1332 BCE, when his successor, Tutankhamun, restored the capital to Thebes.

5 View gallery

Archaeological excavations around the ancient city of Akhetaten, modern-day Amarna

(Photo: Amarna Project)

For generations, scholars blamed a plague, citing textual sources such as Hittite prayers describing an epidemic spreading from Egyptian prisoners of war, and the cache of Amarna letters referring to outbreaks in Megiddo, Byblos, and Sumur. However, none of these texts mention a plague in Akhetaten itself.

5 View gallery

A burial plot near Akhetaten, where three individuals were laid to rest

(Photo: Dr. Gretchen Dabbs, Dr. Anna Stevens)

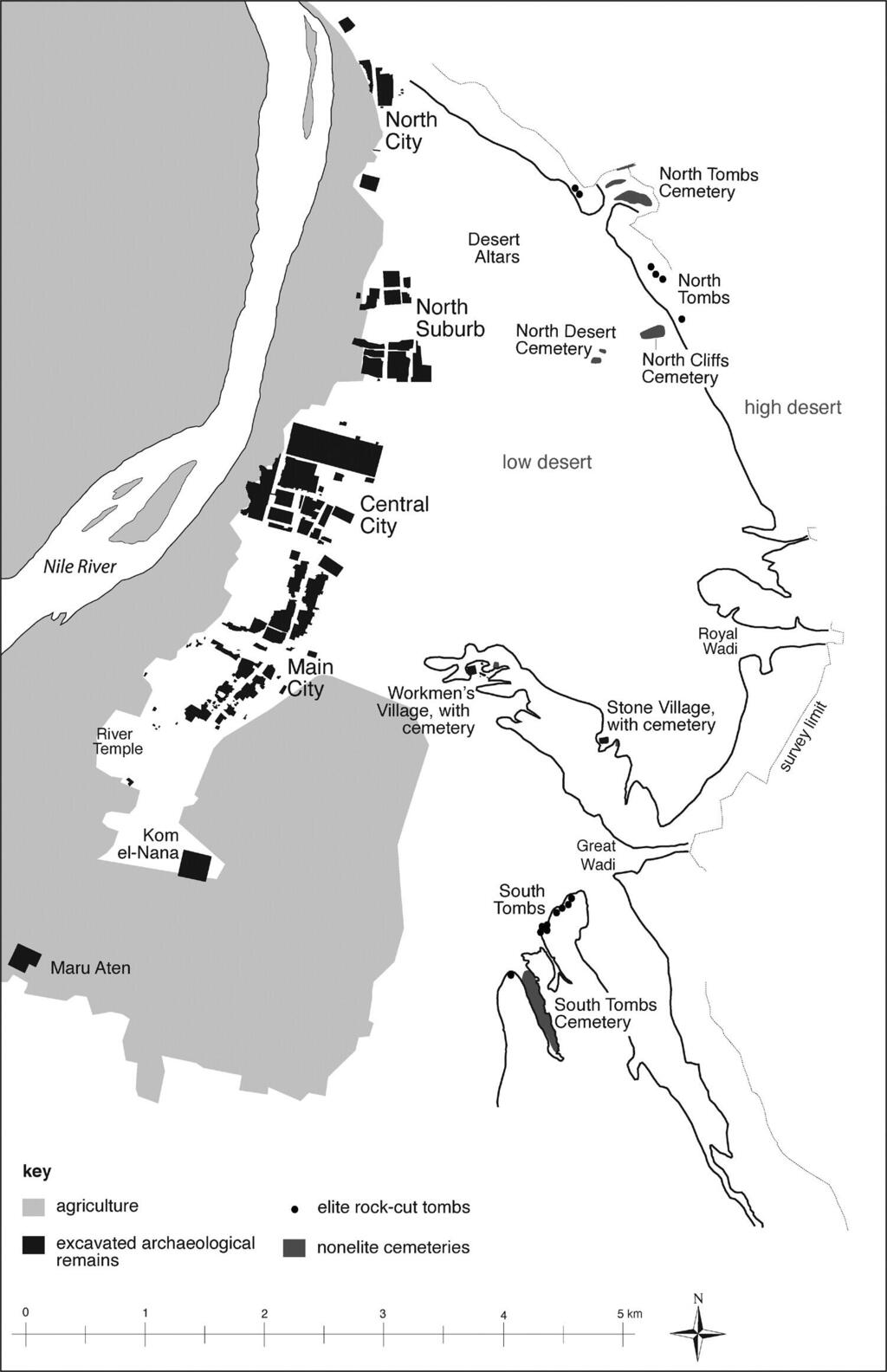

To test the theory, Dabbs and Stevens examined hundreds of burials from four main cemeteries surrounding the city, known as the South Tombs, North Cliffs, North Desert, and North Tombs, containing an estimated 11,350 to 12,950 graves. Excavations between 2005 and 2022 uncovered 889 burials analyzed in this study. The skeletal remains showed evidence of physical hardship: short adult height, spinal injuries, tooth enamel defects, and osteoarthritis, signs of economic and social stress, not epidemic disease. Signs of infection were rare; tuberculosis appeared in just seven cases.

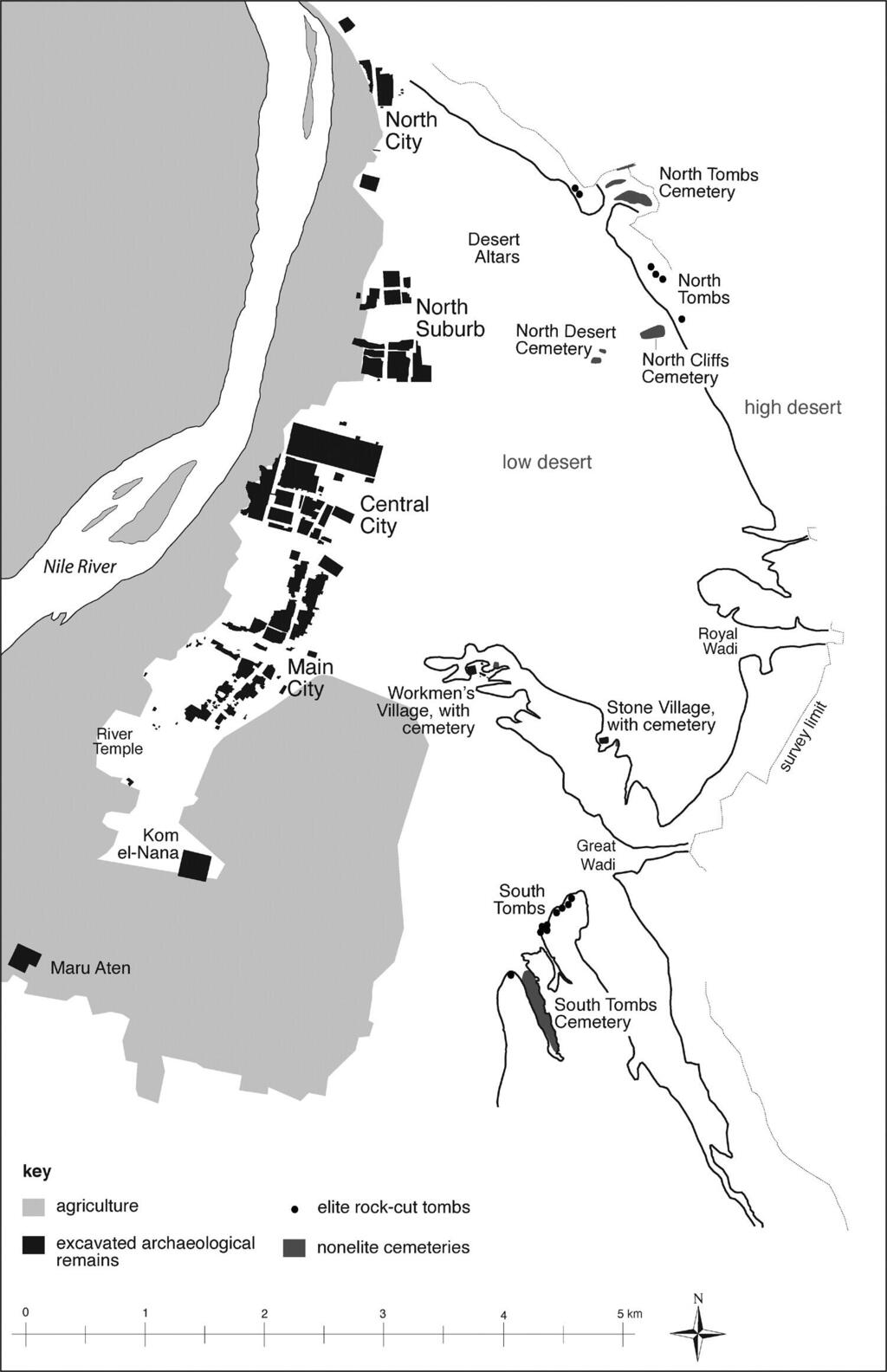

5 View gallery

Various burial positions of individuals interred in cemeteries near Akhetaten

(Illustration: Amarna Project)

Most bodies were carefully buried with coffins, textiles, and grave goods. Their orderly placement suggested that burial practices remained deliberate, not rushed, as would be expected during a mass mortality crisis.

Even the city’s abandonment pattern does not fit a plague scenario. Evidence shows it was vacated systematically, with belongings carefully collected, and the process continued even after Akhenaten’s death. It is therefore unlikely Akhetaten ever suffered a plague.

The findings indicate that Akhetaten’s decline stemmed from political and social shifts following Akhenaten’s controversial reign. The study challenges long-held assumptions, offering a clearer picture of life—and death—in one of ancient Egypt’s most enigmatic cities.

Egyptian sources offer several links between Amarna and outbreaks of disease. In addition to the Hittite prayers connecting a deadly mortality event with the Egyptians and the cache of letters discovered in the city that hint at spreading illness, Pharaoh Amenhotep III also commissioned numerous statues of Sekhmet, the goddess of Memphis who, according to Egyptian mythology, warded off disease and whose priestesses tended to the sick.

5 View gallery

A map of the city of Akhetaten, showing the locations of its cemeteries and other key sites

(Illustration: Amarna Project)

Dr. Dabbs explained that these examples formed a web of circumstantial evidence linking Amarna and Akhenaten’s royal family to illness, connections drawn mainly from written records produced in different places and periods. “Once that association was planted, it became accepted as ‘fact’ through repetition,” Dr. Dabbs said. “One of the main points we wanted to emphasize in our study is the need for caution when using data from other times and regions to make specific claims about Amarna or any ancient site.”