The extent of American ignorance about Greenland is on full display in a wave of viral AI-generated videos circulating across social media this past week. The clips show a snow-covered expanse, adorned with massive American flags and a shopping mall filled with familiar U.S. brands—including, of course, fast food chains. “Soon, the people of Greenland will be free,” reads the caption, referring to the island’s 57,000 residents who already live in freedom and are unlikely to trade free health care, education and social services for genetically engineered chicken nuggets at McDonald’s. But a confused and divided America appears to be returning to its imperial roots—regardless of whether the target is a historic NATO ally.

What recently seemed like another bizarre whim from Donald Trump is now becoming a real possibility. “You have to take Trump seriously—no one believed we’d actually invade Venezuela and run their government,” said senior Democratic Senator Chris Murphy over the weekend. “I can’t believe I have to post a video warning about a U.S. war against NATO, against Europe. I can’t believe this is real life.”

3 View gallery

Trump has been talking about taking over Greenland since his first term

(Photos: Alex Brandon/AP, Reuters)

The treasures of Greenland

Trump floated the idea of acquiring Greenland as early as his first term. In 2019, he expressed interest in buying the island, calling it a “large real estate deal,” and explained: “Look at its size. It’s huge. It should be part of the United States.” When Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen dismissed the idea as “absurd,” Trump took offense and canceled a scheduled visit to Copenhagen.

After the 2020 election and especially after the events of January 6, Frederiksen believed the issue was behind her. But Trump, now back in the White House and more unrestrained than ever, has reignited the push. This time, the threat feels far more real.

“We’ve reiterated Denmark’s position repeatedly, and Greenland has made clear again and again that it does not want to become part of the United States,” Frederiksen said. This time, she added a warning once considered unthinkable: “These actions could lead to the collapse of the NATO alliance.”

That prospect does not appear to concern Trump, who has always resented U.S. alliances with Europe, believing they cost America more than they benefit it. Contrary to popular belief, Trump is not an isolationist—he’s an imperialist. In his worldview, the planet belongs to strong empires, free to take what they want from weaker nations—be it Venezuela’s oil or Greenland’s rare earth riches.

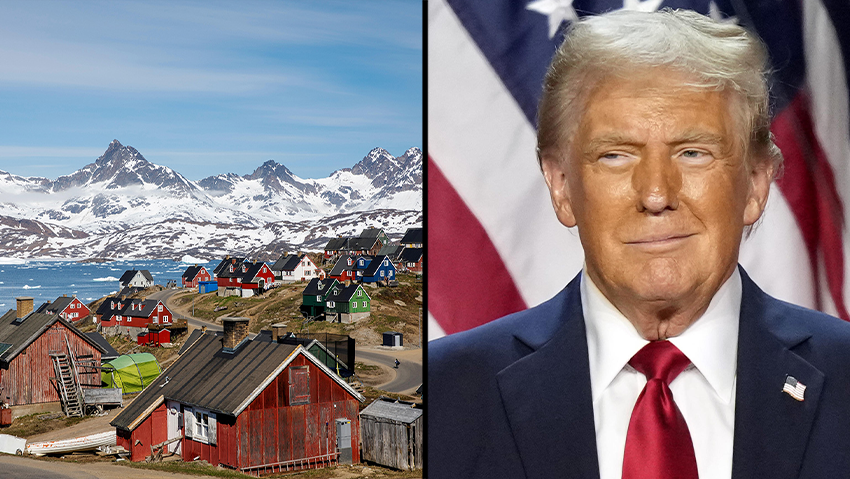

3 View gallery

Greenland is the world’s largest island at 2.16 million square kilometers

(Photo: Ian Schofield, Shutterstock)

Greenland, the world’s largest island at 2.16 million square kilometers, is a former Danish colony and now an autonomous territory of Denmark located in the Arctic. It was incorporated into Denmark in 1953 during the post–World War II decolonization wave. In 1979, Greenland was granted limited self-rule, and in 2009 it became fully autonomous—though Denmark still controls its foreign and defense policy. About 81% of the island is covered in ice, and its 57,000 residents travel between towns by boat, helicopter and plane. Nearly 90% of the population is Greenland-born, primarily of Inuit descent.

Greenland’s economy revolves around fishing, but also includes services, tourism, a growing mining industry and substantial financial support from Denmark. The island’s GDP is about $3.3 billion annually, with a 2023 per capita GDP of roughly $58,500—comparable to wealthy European nations, though heavily reliant on Danish aid. Denmark provides an annual grant of around 4.5 billion kroner (about $700 million), which accounts for 18%–20% of Greenland’s GDP and nearly half of its government revenue. The overall tax rate hovers around 30%, moderate by Nordic standards.

Greenland’s exports consist almost entirely of fish and seafood. Since 1979, the island has consistently run a trade deficit, importing more than it exports. Official unemployment ranges from 5%–6%, and roughly 12% of the workforce is foreign-born. “No individual can own land in Greenland, which makes the notion of our country as real estate even more provocative for us,” Greenlandic filmmaker Inuk Silis Høegh told CNN.

Strategic value in a warming world

Three factors make Greenland strategically vital—all amplified by the climate crisis that Trump denies publicly but clearly understands: its geopolitical location, its natural resources and the emerging Arctic shipping lanes. Greenland lies between the U.S. and Europe and straddles the so-called GIUK gap (Greenland–Iceland–UK), a critical maritime passage connecting the Arctic to the Atlantic. It is vital for tracking Russian naval activity, giving the U.S. a key vantage point over access to the North Atlantic, both for commerce and security.

Greenland’s resource wealth further enhances its value—especially as China leverages its control of the global rare earths market. As Arctic ice melts, Greenland’s mineral riches are becoming more accessible. The island holds vast deposits of rare earth elements like neodymium, praseodymium, dysprosium, terbium, and cerium—essential for electronics and wind turbines. It also has uranium and thorium, critical for nuclear energy, as well as niobium, tantalum, beryllium, zirconium, fluorine, graphite, copper, nickel, zinc, lead, iron, gold and diamonds.

Trump has downplayed the importance of these resources. “We need Greenland for national security, not minerals,” he said, adding: “There’s no such thing as rare earth. It’s everywhere—it’s just supply and demand.” Those who have worked with Trump see it differently. Mike Waltz, now U.S. Ambassador to the UN, said last year that Trump is focused on “critical minerals” and “natural resources” in Greenland.

Nervous Europe

Trump resumed serious talk about Greenland the day after the U.S. captured Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro. “Greenland is covered with Russian and Chinese ships everywhere,” Trump said. “We need Greenland from a national security standpoint, and Denmark can’t guarantee that.” The following day, the White House confirmed it was “exploring a range of options” for acquiring Greenland, adding that all options—including military—were on the table.

Secretary of State Marco Rubio told members of Congress last week that the administration is considering purchasing Greenland, and that the military option “is not serious.” That might have reassured lawmakers—if Rubio hadn’t also once promised that the U.S. wouldn’t intervene militarily in Venezuela.

In 1946, when Greenland had no autonomy, Denmark rejected President Harry Truman’s offer to buy the island for $100 million in gold. Five years later, the U.S. signed a defense agreement with Denmark granting it wide military access to Greenland. Today, the U.S. maintains one remote base on the island, but the 75-year-old agreement allows the U.S. to “construct, install, maintain and operate” military bases across Greenland, “retain personnel,” and “control landings, takeoffs, docking, movement and operation of ships, planes and naval vessels.”

That agreement was signed with Denmark—but Greenland now has the right to hold a referendum. Danish officials say it is the island’s residents who will decide their future. A poll last year found that 85% of Greenlanders oppose U.S. control. The 2004 update to the defense agreement formally included Greenland’s semi-government. “The U.S. has such a free hand in Greenland that it can do pretty much whatever it wants there,” Mikkel Runge Olesen, a researcher at the Danish Institute for International Studies in Copenhagen, told The New York Times. “But Greenland doesn’t want to be bought—especially not by the U.S. And Denmark doesn’t have the authority to sell it. It’s impossible.”

Trump’s renewed focus on Greenland, immediately following the U.S. operation in Venezuela, has triggered panic in Europe. Leaders from France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Spain, the UK and Denmark—who remained silent after the Caracas raid—were alarmed to realize they might be next. They quickly issued a joint statement: “Greenland belongs to its people. Only Denmark and Greenland will decide on matters concerning Denmark and Greenland.”

NATO’s Article 5 declares that an attack on one member is an attack on all. The only time Article 5 has been invoked since NATO’s founding in 1949 was after the 9/11 attacks. Forty-three Danish soldiers were killed in Afghanistan alongside U.S. troops. But if the U.S. forcibly takes Greenland, it would plunge NATO into an existential crisis.

Trump doesn’t seem concerned. “We’re going to do something in Greenland,” he said over the weekend. “Whether they like it or not. It can be done the easy way or the hard way.”

First published: 10:05, 01.13.26