Recent developments in northeastern Syria have returned the Kurds to center stage. They are a large ethnic minority living on their historic homeland who have never achieved state sovereignty and who, over the past decade, came closer than ever to realizing self-rule.

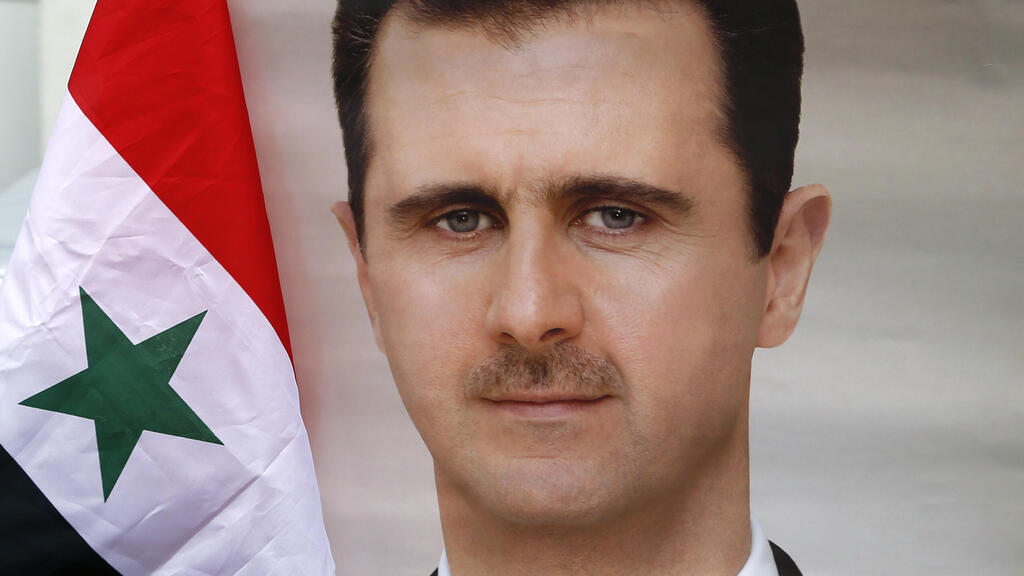

Now, with the shift in the balance of power in Damascus and the transition from the long rule of Bashar Assad to a government led by Ahmad al-Sharaa, those gains are in real danger. Kurdish autonomy, born out of the chaos of the civil war, is facing a renewed effort to rebuild a centralized Syrian state, and the Kurds are once again being forced to fight for their place.

An ancient people without a state

The Kurds are one of the largest ethnic groups in the world without a state. About 30 million people live in a contiguous geographic area stretching across Turkey, Iraq, Iran and Syria, but the colonial division of the Middle East in the 20th century split them among foreign nation-states. In Syria, Kurds make up about 8% to 10% of the population, roughly 2 million people, concentrated mainly in the north and northeast of the country. These areas are not merely geographic peripheries but strategic assets that include oil fields, water resources and vast agricultural lands.

Despite the depth of their historical roots, Kurds were never recognized in Syria as a legitimate national group, despite their aspirations for national existence and cultural rights within what is known as Kurdistan, a historic region without an independent state. Kurdish identity was viewed as a threat to the concept of a unified state, and the desire to preserve strong central rule led governments in Damascus to suppress it rather than accommodate it.

Since the Ba'ath Party came to power in the 1960s, and even more so under the Assad family, Kurds lived under systematic repression. The citizenship of hundreds of thousands of Kurds was revoked, leaving them stateless. The Kurdish language was banned from public life, villages and towns were renamed with Arabic names, and any attempt at independent political or cultural activity was defined as subversive. Kurds lived inside Syria but outside its “social contract.”

This policy stemmed not only from domestic concerns but also from the regional context. Damascus closely watched developments in Iraq, where Kurds succeeded in establishing broad autonomy, and feared similar consequences on its own territory.

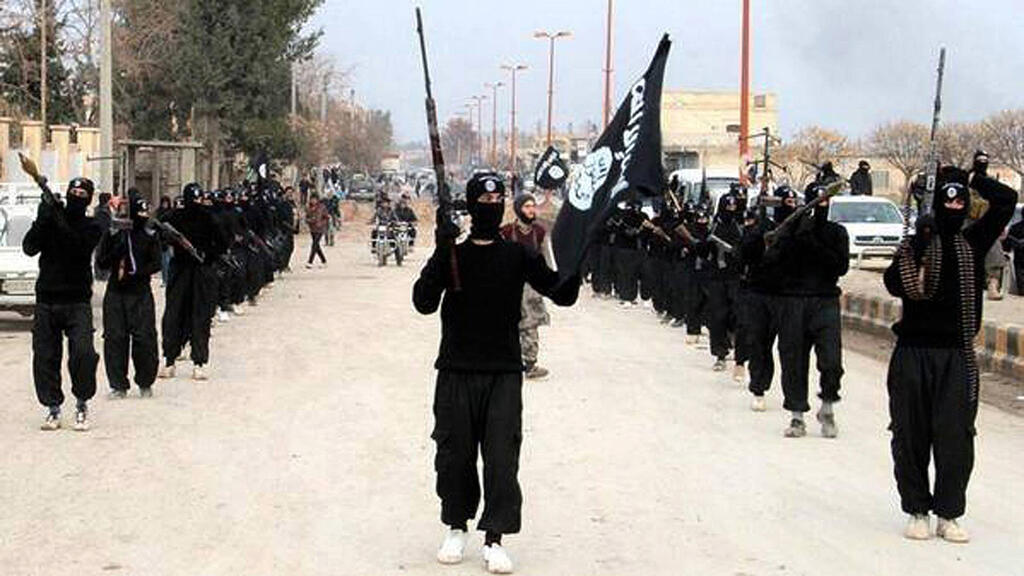

The civil war and the fight against ISIS

From the Syrian government’s perspective, recognizing meaningful Kurdish rights was seen as opening the door to undermining the structure of the state as a whole. The outbreak of the Syrian civil war in 2011 transformed reality. As the Assad government fought for survival in major population centers, large parts of the northeast were effectively abandoned. Kurds quickly moved into the vacuum, establishing local security forces, civil councils and governing mechanisms. Gradually, they built an undeclared autonomous entity known as Rojava.

This autonomy was based on a distinctive model of decentralized local governance, gender equality and the inclusion of ethnic and religious minorities. For Kurds, it was the first time they could manage their political and civic lives without direct intervention from Damascus.

The rise of the Islamic State group in 2014 turned the Kurds from a local actor into a central partner on the international stage. The battle for Kobani marked a turning point, delivering a significant defeat to the Islamic State after a string of victories against multiple armies and organizations in Iraq and Syria. Fierce Kurdish fighting, alongside U.S. air support, made them preferred Western allies.

In 2015, the Syrian Democratic Forces, or SDF, were formed, a military alliance made up of about 80% Kurdish fighters and 20% members of other communities. They united to fight Islamist terrorist organizations such as the Islamic State and Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, then led by Syria’s current president, Ahmad al-Sharaa, who was known at the time as Abu Mohammed al-Golani. Over the years, they also fought Syrian government forces and Turkish troops.

From that point on, the SDF became the backbone of the campaign against the Islamic State. They bore most of the ground fighting, paid a heavy price in lives and in return received military and political support from the United States. Within a few years, they controlled about a third of Syrian territory, including Raqqa, the former capital of the self-declared caliphate. At their peak, the Kurds effectively ran a state without formal recognition.

The peak of autonomy, the cracks — and the Arab world’s silence

The past decade marked the height of Kurdish power in Syria. Kurds controlled key oil fields, strategic dams and border crossings and established functioning civilian institutions. Yet beneath the surface, deep vulnerabilities were exposed. The autonomy relied almost entirely on the U.S. presence. Turkey viewed Kurdish forces as a direct threat and repeatedly acted against them militarily. No binding constitutional arrangement was ever reached with Damascus. The autonomy endured as long as the interests of global powers aligned with those of the Kurds, but once the regional balance shifted, its survival became fragile.

For Turkey, Kurds in Syria are seen as an existential security threat. Ankara views them as an extension or ideological inspiration of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or PKK, and refuses to distinguish between different Kurdish forces. Since the start of the Syrian civil war, Turkey has worked consistently to prevent a continuous Kurdish territorial belt along its southern border through military operations, buffer zones and the use of local militias. Any Kurdish advance is perceived as a Turkish strategic loss.

By contrast, the United States viewed the Kurds as a tactical rather than a strategic partner. The alliance was born out of the need to fight the Islamic State, but Washington avoided committing to a political arrangement that would guarantee long-term Kurdish autonomy. The U.S. desire to preserve relations with Turkey and avoid deep entanglement in Syria led to a cautious and at times inconsistent policy. For the Kurds, it was support that enabled achievements but did not guarantee a future.

Russia, for its part, sees preserving Syria’s unity as a core interest and supports the central government in Damascus, especially when its ally Assad was in power. Although it maintained tactical contacts with the Kurds, at decisive moments Moscow always preferred strengthening the centralized state. Iran also supports curbing Kurdish autonomy, fearing domestic repercussions and damage to its axis of influence through Damascus. More broadly, Arab states tend to remain silent on the Kurdish issue, wary of encouraging separatist trends elsewhere.

Since al-Sharaa came to power after Assad’s fall about a year ago, he has sought to reunify Syria. The new leadership views Kurdish autonomy as a temporary product of chaos, not a foundation for a future political order. Reports that forces linked to the new government have carried out brutal massacres against members of the Alawite and Druze minorities since his rise have only heightened Kurdish fears of relinquishing their autonomy.

In March last year, an agreement was reached between al-Sharaa and Druze leaders that was seen at the time as dramatic. It called for integrating SDF forces into the Syrian army and incorporating their civilian institutions into state structures. Yet no real progress has been made toward implementing the deal. On the ground, however, developments have moved in the opposite direction. In recent weeks, government forces have advanced into Kurdish-held areas, a push that peaked in recent days as they seized strategic territories and resources while Kurdish forces were forced to retreat.

Why the Kurds matter to Israel?

The Kurds claimed earlier this week that Israel had offered them assistance. This is not surprising. From Israel’s perspective, Kurds in Syria are not formal allies, but they are an actor of indirect strategic importance. Over the years, Kurds have been seen as a non-hostile force that fought the Islamic State and to some extent balanced the influence of Iran and Hezbollah in northern Syria. A strong Kurdish autonomy created a space not directly controlled by Damascus or Tehran, complicating the consolidation of the Iranian axis.

The weakening of the Kurds strengthens Syria’s central government and its allies, including Turkey, and brings Israel’s northern frontier closer to a reality in which hostile actors operate with greater freedom. A fragmented, weak Syria crowded with local players served Israeli interests more than a centralized Syria capable of restoring sovereignty. At the same time, overt Israeli support for the Kurds could trigger escalation with Turkey and the new Syrian government. As a result, Jerusalem is keeping a low profile, especially as it conducts negotiations with Damascus over a security arrangement mediated by Washington.

Once again, Syria’s Kurds stand at a historic crossroads after a decade of autonomy that offered a taste of self-rule. Even in the post-Assad era, they find themselves back at a familiar point, without strong diplomatic backing to secure their future.