Iran acknowledged earlier this week that more than 3,000 people have been killed since protests erupted across the country last month. Other reports place the toll far higher, with the opposition channel Iran International reporting more than 12,000 dead in what it described as “the greatest massacre in history.”

Asked on Wednesday about the number of fatalities, U.S. President Donald Trump said, “No one has been able to give me an exact number. I’ve heard numbers. I think it’s a lot. It’s too many.”

Trump is far from alone in not knowing how many people have truly been killed. The gap between the figures is not accidental. Iran is a relatively closed country, without a free press and under severe restrictions on documentation, internet access and the activity of international organizations. In such conditions, definitive conclusions are nearly impossible.

What is clear is that if the higher estimates are accurate, the world is witnessing one of the deadliest protest crackdowns in modern history, with almost no precedent for the suppression of a civilian uprising on this scale. The real question is not only how many people were killed in Iran, but why, in almost every case of mass protest, the exact number of deaths remains a mystery. The debate over casualty figures is not merely technical. It is part of a struggle over narrative. Regimes have a clear interest in minimizing the toll to avoid international pressure and sanctions. Opposition groups have an incentive to inflate numbers to generate urgency and support. Human rights organizations often fall somewhere in between, but remain dependent on limited access and fragmentary information.

So how can deaths in protest crackdowns be counted at all? Which historical cases resemble the current unrest in Iran? And why do the true numbers so often remain contested?

Blurred figures with no absolute count

Unlike wars between states, where formal armies and official records exist, protests unfold within civilian populations. Killings do not take place on defined battlefields but in streets, squares and even private homes. Victims are often buried quickly, sometimes without official documentation. Families fear reporting deaths, and authorities are frequently part of the concealment.

Trump: 'It appears that people were killed who should not have been killed.'

Even the definition of a “protest fatality” is unclear. Should the count include only those killed during demonstrations, or also those who died of their wounds days later, prisoners who died under interrogation or bystanders caught in the violence? Each decision can alter the figures by thousands.

Under authoritarian regimes, the problem intensifies. Control over media, internet shutdowns, intimidation and threats against medical staff turn counting itself into a political act. This difficulty is not unique to Iran. It spans eras, regimes and continents. The further back one goes in history, the harder it becomes to estimate casualties, not only because of the absence of visual documentation, but because systematic counting was often not the norm.

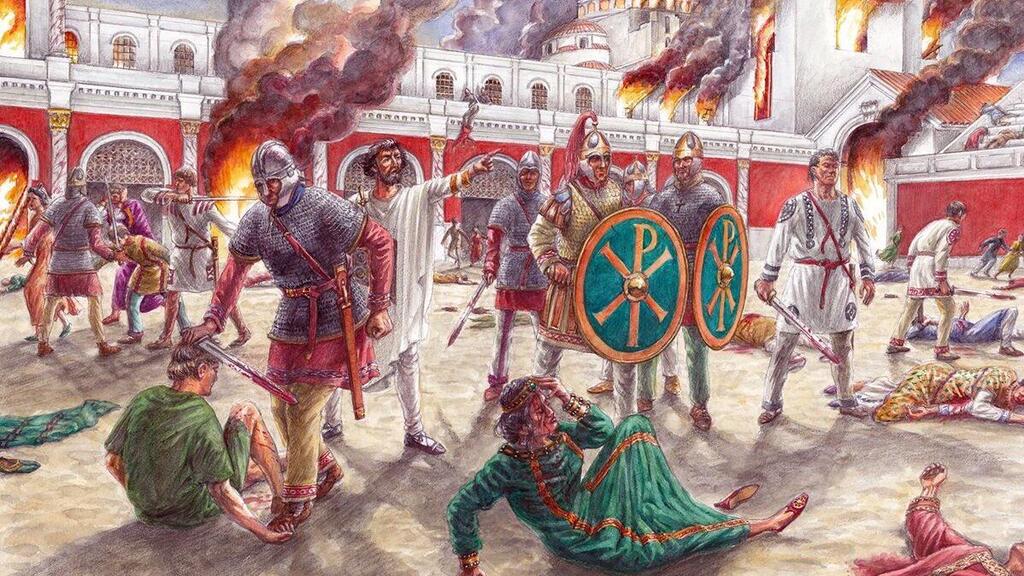

The Nika revolt (532): 30,000 to 35,000 dead

One of the earliest examples is the Nika revolt in Constantinople, the capital of the Eastern Roman, or Byzantine, Empire, located in present-day Istanbul. The uprising lasted about a week in 532 and began as riots by chariot racing factions before turning into a mass rebellion against Emperor Justinian.

According to historical accounts, the emperor ordered his forces to slaughter the rebels gathered in the Hippodrome. Estimates in surviving sources range from 30,000 to 35,000 dead. These accounts were written years later by interested parties, without names or verifiable records. The numbers may have been intended to emphasize imperial power, or they may understate an even harsher reality. Later urban uprisings across Europe, China and the Ottoman Empire were also crushed with extreme violence, claiming thousands of lives, yet recorded only in vague terms such as “many were killed.” Sources from the 14th and 15th centuries speak of “thousands dead” or “cities emptied of their inhabitants,” often without any attempt at precise figures.

The Paris Commune (1871): 10,000 to 20,000 killed

In 1871, the suppression of the Paris Commune became one of the bloodiest episodes in early modern European history. After France’s defeat in the war with Prussia, Paris was controlled for months by members of the Commune, a radical political and social movement. When the government retook the city, it launched a violent crackdown during what became known as the “Bloody Week.” Estimates of the death toll range from 10,000 to 20,000.

Some were killed in street fighting, others executed without trial, and many died later in prison or from their wounds. Distinguishing protesters from improvised fighters or uninvolved civilians proved nearly impossible, and urban revolt descended into chaos where counting itself collapsed.

Tiananmen Square (1989): a number never released

The arrival of the 20th century did not solve the problem, it merely changed its form. In 1989, the suppression of student protests in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square became a global symbol of state violence. The crackdown was widely filmed and broadcast worldwide. Yet more than three decades later, no official death toll exists. The Chinese government has never released full data, and conflicting testimonies persist.

Western estimates speak of hundreds killed, while other sources claim thousands, and some extreme scenarios suggest figures approaching 10,000. This uncertainty has become central to Tiananmen’s legacy, and mirrors the situation unfolding in Iran today.

Myanmar’s 8888 uprising (1988): 3,000 to 10,000 killed

On August 8, 1988, a nationwide uprising erupted in Myanmar, then Burma, against the ruling military junta. Known as the 8888 uprising, it involved strikes, marches and mass demonstrations. The military responded with direct fire on protesters. Most estimates cite about 3,000 deaths, though some place the toll closer to 10,000. The official figure released by the regime was just 350.

Despite relatively extensive documentation, no comprehensive list of victims exists, and the figures remain estimates based on testimonies and later reports.

Egypt 2013: up to 2,600 killed in a single day

Another prominent case is the violent dispersal of protest camps at Rabaa al-Adawiya Square and Nahda Square in Cairo on August 14, 2013. Egyptian security forces used live fire to clear sit-ins by supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood and ousted President Mohamed Morsi. Human Rights Watch documented at least 900 deaths that day, while other sources, including protest supporters, claimed as many as 2,600 were killed.

9 View gallery

Detainees during the protest at Rabaa al-Adawiya Square in Cairo, Egypt, 2013

(Photo: Reuters)

The defining feature of this case was the scale of violence compressed into a single day, with extensive documentation. Even so, the figures remain disputed.

Syria 2011: when protest turned into war

The protest wave that erupted in Syria in March 2011 began as a largely nonviolent civilian uprising demanding political reform and the end of Bashar Assad’s rule. In the early months, thousands of protesters were reportedly killed by security forces. However, the violence escalated rapidly. Armed resistance emerged, military officers defected and within months the conflict devolved into a full-scale civil war. At that point, distinguishing protest deaths from war casualties became nearly impossible.

9 View gallery

Assad. In Syria’s case, the protest quickly turned into a civil war

(Photo: Abdulaziz Ketaz / AFP)

For this reason, Syria is often excluded from historical comparisons focused solely on protest crackdowns, despite its origins as a case of violent suppression of civilian dissent.

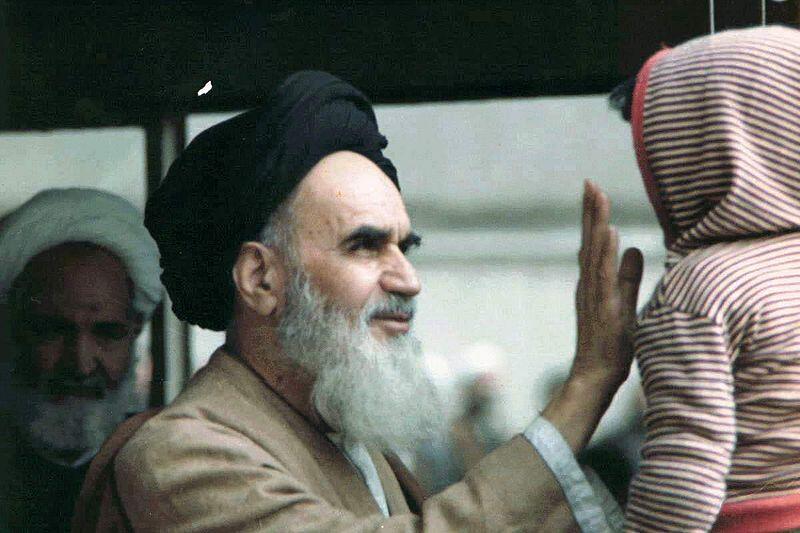

Iran in the 1980s: executions far from the streets

Iran itself offers a grim precedent. After the 1979 Islamic Revolution, the new regime under Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini violently eliminated political opponents. The peak came in 1988, when thousands of political prisoners were executed over several months.

Human rights groups estimate at least 4,000 to 5,000 victims, while other assessments suggest significantly higher numbers. Most were prisoners already in custody, executed after summary proceedings by so-called death commissions. This was not a street protest crackdown but a systematic massacre behind prison walls. Yet more than three decades later, there is still no agreed figure. Mass graves were concealed, documents destroyed and no official data released.

Today’s Iran: a different league

Iran today is a 21st-century state with social media, citizen documentation and international reporting. At the same time, it is a regime that imposes communication blackouts, restricts journalists and exerts heavy pressure on families and hospitals.

9 View gallery

Body bags in Iran during the current protests; a human toll far heavier than can ever be counted with precision

If the higher estimates of the current protest death toll are confirmed, the events would approach historic extremes. Even if the numbers prove lower, the scale of violence remains extraordinary by modern standards. What unites all scenarios is uncertainty. The true number may emerge only years from now, or it may never be known, just as in the historical cases before it.

What is already clear is that the current figures far exceed those of previous protests in Iran. During the 2009 Green Movement, which followed disputed elections, millions protested and dozens were killed. In the 2019 fuel price protests, hundreds died, with a Reuters report later placing the toll at 1,500. In the 2022 hijab protests, about 500 were killed. The numbers now being discussed recall only the executions of the 1980s, when the Islamic Republic consolidated power through mass repression.

It is impossible at this stage to determine how many people have been killed in the current unrest. But the fact that within just over two weeks, estimates already range into the thousands, and even tens of thousands, places this protest in a different category altogether. If the higher figures are confirmed, the world may be witnessing one of the deadliest crackdowns on civilian protest in the modern era, at a human cost far greater than can ever be counted with precision.