Nearly 800 days after the October 7 massacre, Israel still lacks a finalized legal framework for prosecuting the hundreds of terrorists captured during the attack, as the Knesset’s Constitution, Law and Justice Committee continued Wednesday to prepare a bill establishing a special tribunal for their trials.

The proposal, advanced by committee chair Simcha Rothman of Religious Zionism and Yulia Malinovsky of Yisrael Beytenu, would create a special court empowered to try suspects for genocide-related offenses under Israel’s 1950 Genocide Prevention and Punishment Law. The court would include 15 judges and would be permitted to deviate from standard evidentiary rules. The justice minister would be authorized to set accompanying regulations.

Malinovsky told the committee that for the first time, the judiciary had acknowledged in a formal document that the captured terrorists could face the death penalty under the proposed framework. “Israel has for the first time recognized that the Nukhba terrorists may face capital punishment,” she said. “We will soon vote to advance this law toward justice.”

The bill also calls for a policy steering team to oversee prosecutorial decisions. The panel would include representatives of the justice, defense and foreign ministers. In addition, the legislation proposes amending the law governing unlawful combatants to authorize the IDF chief of staff to issue detention orders for suspects reasonably believed to have taken part in the October 7 massacre.

Mounting logistical, legal and operational hurdles

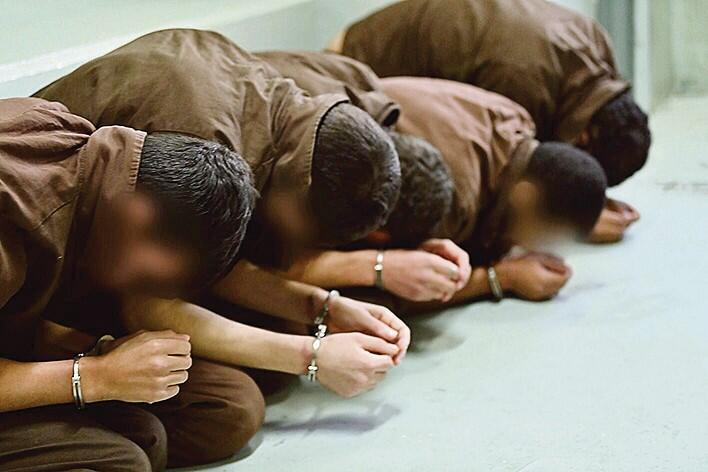

Officials briefed the committee on the unprecedented challenges of prosecuting roughly 350 terrorists, many of whom participated in multiple crime scenes across southern Israel.

Representatives of the military prosecution said the plan would require building an entirely new judicial system. Maj. Michelle Selby, head of legislation at the Military Advocate General’s Corps, warned that creating a new court would have “significant implications for substantive law, offenses that may not be chargeable, procedure, judicial appointments and international legitimacy,” since proceedings would take place in a military court.

A major obstacle is staffing. The military prosecution would need dozens of additional prosecutors, which currently do not exist within the system. Funding would have to come from outside the IDF budget, Selby said, as the military is not prepared to establish such an apparatus.

He added that transferring files to newly recruited prosecutors would risk losing “thousands of hours of work” already completed by the special investigative team handling the cases for the past year and a half. Infrastructure is also an issue: military courts in the West Bank cannot be used, meaning a new complex would have to be built.

How to structure the trials

South District Attorney Erez Padan told the committee that the prosecution is weighing three options:

1. One sweeping indictment covering all suspects — a model used in Italy in mass mafia trials.

2. A hybrid approach, beginning with a unified proceeding for preliminary motions, followed by separate trials divided by geographic sectors or terrorist cells.

3. Dozens of separate indictments.

With 49 distinct attack zones — communities, bases and road junctions — prosecutors said many terrorists moved across multiple locations, creating overlapping evidence and complicating indictment strategy.

Padan stressed that any chosen model must guarantee “fair process, public hearings, rights of appeal and professional prosecution” consistent with democratic standards.

Government tensions and criticism from lawmakers

Rothman criticized what he described as insufficient preparation by government ministries and a lack of cooperation between Justice Minister Yariv Levin and Attorney General Gali Baharav-Miara, which he said was slowing progress.

The Courts Administration presented a document assessing the implications of using existing courts. Its chief legal adviser, Barak Lizer, said the most suitable venue would be the Be’er Sheva District Court, located in the region where the attacks occurred, and that proceedings should be conducted “as efficiently and swiftly as possible.”

Lizer also noted that selecting the venue depends heavily on the number of indictments and the security and logistical demands of hosting such large-scale trials. Ideas under consideration include afternoon court sessions to reduce strain on the system or adapting public buildings in the south to serve as temporary judicial facilities.

As the committee continues its work, officials emphasized that without a coordinated government plan, additional funding and a clear procedural framework, Israel will struggle to bring the October 7 terrorists to trial in a timely manner.