The Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro’s arrest Saturday in Caracas by U.S. forces, on the orders of President Donald Trump, places at the center of debate one of the sharpest tests international law has faced in decades.

This is not a political or moral question, but a purely legal one that strikes at the heart of the international order: May a state arrest a sitting president of another state, and what are the limits of such authority under accepted rules of international law?

Under customary international law, the immunity of sitting heads of state is considered a foundational principle. This principle is not anchored in a single specific treaty, but is based on consistent state practice and international jurisprudence, foremost the 2002 ruling of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in the Arrest Warrant case — a legal dispute between Congo and Belgium concerning an arrest warrant issued by Belgium against the Congolese foreign minister.

In that case, the court held that a sitting head of state, head of government or foreign minister enjoys absolute personal immunity from arrest and prosecution by a foreign state, even when accused of serious crimes under international law.

The logic behind this ruling is not to protect the individual, but to safeguard the functioning of the state and international relations, based on the view that the arrest of a senior sovereign official by another state could undermine the very ability to maintain a stable international system.

Trump: US will run Venezuela through post-Maduro transition

(Video: Reuters)

This immunity, known as immunity ratione personae, attaches to the individual’s status while in office and is not limited to acts carried out in an official capacity. It also shields against enforcement for private acts and expires only once the individual leaves office. This distinction is particularly important in Maduro’s case, because even if he is accused of grave crimes, as long as he remains the de facto president of Venezuela, personal immunity remains in force under accepted rules.

Alongside customary law, similar principles are reflected in international conventions. The 1961 Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations, for example, states in Article 29 that a diplomat shall be inviolable and not liable to any form of arrest or detention. Although the convention does not directly address heads of state, case law and legal scholarship cite it as an illustration of the broader principle that state representatives enjoy special protection from foreign enforcement. If a diplomat enjoys absolute immunity, the assumption is that a sitting head of state enjoys even broader protection.

International law recognizes that immunity does not amount to absolute criminal impunity, but it sets out defined and limited avenues for action against a sitting head of state. The first is proceedings before a competent international tribunal, foremost the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague.

The Rome Statute establishing the court states in Article 27 that official capacity as a head of state does not exempt a person from criminal responsibility. However, this provision applies only within the court’s own jurisdiction and does not authorize unilateral action by states. In other words, even if immunity does not shield against international criminal responsibility, it does protect against arrest by a single state acting outside an agreed institutional framework.

The second avenue is an explicit decision by the UN Security Council, acting under its powers in Chapter VII of the UN Charter. Such decisions may authorize exceptional enforcement measures, but they require agreement among the council’s permanent members and are therefore rare.

The third avenue arises when the head of state is no longer in office, whether due to the end of a term, removal or regime collapse. At that point, personal immunity lapses, and action may be taken against the individual in national or international forums.

So does Maduro’s arrest meet the criteria?

In Maduro’s case, none of the three legal pathways apply. No proceedings have been initiated against him at the International Criminal Court, the UN Security Council has not authorized enforcement and at the time of his abduction, he still maintained de facto control over the institutions of government and the security forces. This has led many critics of Trump’s decision to argue that the arrest falls outside the accepted framework of international law.

Maduro led away by Federal law enforcement officers in New York

(Video: RapidResponse47)

The U.S., for its part, may invoke the concept of extraterritorial jurisdiction, which allows states to prosecute individuals who harm their vital interests even beyond their borders, particularly in areas such as drug trafficking, terrorism and money laundering. However, international jurisprudence makes clear that the existence of jurisdiction does not override the personal immunity of a sitting head of state. In its Arrest Warrant ruling, the ICJ explicitly held that jurisdiction and immunity are separate issues, and that the presence of one does not negate the other.

Another relevant question is that of recognition and legitimacy. The United States does not recognize Maduro as Venezuela’s legitimate president, but international law does not grant any single state the power to unilaterally deny status or immunity. The prevailing approach is recognition of effective control — that is, actual authority over the machinery of government. Many countries, including major powers such as Russia and China, continue to recognize Maduro as Venezuela’s de facto president, meaning that for the purposes of international law, he is still considered a sitting head of state.

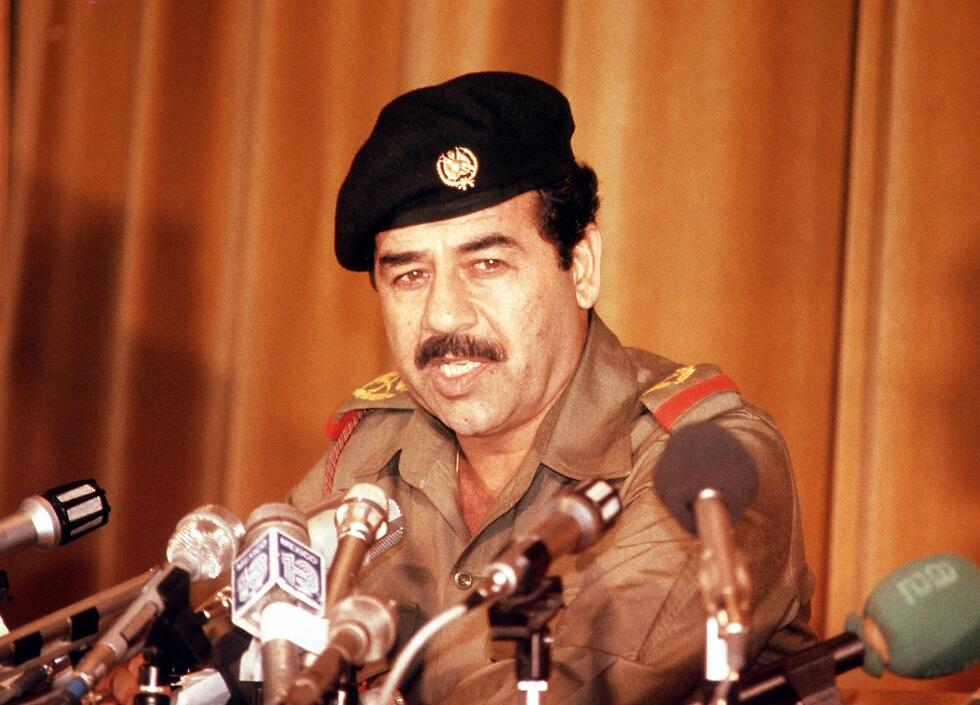

Comparisons to past cases underscore the exceptional nature of this incident. Saddam Hussein, for instance, was arrested by U.S. forces in 2003 only after the invasion of Iraq and the collapse of his regime, when he no longer held effective power. Panama’s leader Manuel Noriega was similarly arrested in 1989 during a large-scale military invasion, after the U.S. had effectively stripped him of his status as head of state. In both cases, personal immunity was no longer in effect at the time of arrest. This is the key legal distinction from the Maduro affair, where immunity, under accepted rules, still applies.

Beyond the immunity issue, other core principles of the UN Charter are also at stake, foremost among them the prohibition on the use of force outlined in Article 2(4), which requires states to refrain from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of another state.

International law also enshrines the principle of non-intervention in the internal affairs of sovereign states. While an arrest is not necessarily equivalent to a military invasion, some interpretations view it as an act of force — or at the very least, coercive interference — especially when carried out without consent or an international mandate.

From a legal perspective, the professional consensus tends to regard the unilateral arrest of a sitting president as a clear deviation from the established norms of international law. Even amid deep political disagreement over Maduro and his policies, legal rules are designed precisely for such contentious situations — to set clear boundaries on the actions of states. The remaining question is not only what the law says in this specific case, but whether the international system will continue to uphold those rules, or allow new precedents in which state power overrides established legal frameworks.

International law has no police, and Trump is the sheriff

One of the central issues raised by Maduro's arrest has less to do with what international law says and more to do with how it is enforced. Unlike domestic criminal law, which operates through defined enforcement mechanisms, international law functions in a system without centralized authority. There is no supranational body with its own independent police force, so legal rules rely almost entirely on inter-state cooperation and voluntary restraint.

In such a system, any unilateral action by a powerful country is not merely seen as applying the law—it is perceived as reshaping the enforcement reality itself. When a state acts alone against a sitting head of state, it is not just interpreting international law; it is stepping into the role of enforcer. This shift alters the foundational balance of the international legal order, transferring weight from institutions to raw power.

That’s one reason even countries critical of Maduro or opposed to his regime have been cautious in publicly supporting the move. Their concern is not solely legal—it is institutional: if any country can enforce its own reading of international law through force, then the rules themselves lose their restraining effect.

And Trump? The extraordinary and unprecedented action he took aligns closely with the foreign policy vision he has long championed, one that seeks to reduce reliance on international institutions. Trump has repeatedly expressed skepticism toward global courts and the United Nations, claiming they constrain U.S. freedom of action. In that light, American actions are less about consensus and more about asserting a unilateral interpretation of authority and legitimacy. So it's little surprise that the world’s self-declared new sheriff chose to go after Maduro.