U.S. President Donald Trump famously claims that the most beautiful word in the English language is “tariffs.” But since returning to the White House for his second term, a different word seems to bring him even more pleasure: autopen.

Every time Trump sits behind the golden desk in the even more golden Oval Office to sign executive orders in front of the cameras, he eventually repeats a familiar accusation: that his predecessor, Joe Biden, didn’t sign key documents himself, but left the job to a machine. In Trump’s eyes, this isn’t a mere technicality but a fundamental flaw: proof, he insists, that Biden was unfit for office, unaware of his actions and certainly not responsible for the signatures that bore his name.

Trump admits he used an autopen—but, he claims, only for “unimportant documents.” He maintains it’s unthinkable for anyone to sign a dramatic presidential pardon, whether for a family member or a death row inmate, with anything other than their hand. This week, what began as a tongue-in-cheek media skirmish took a serious legal turn. Trump ordered the Justice Department to launch an investigation. Ed Martin, the attorney overseeing presidential pardons, has been directed to examine whether Biden’s use of an autopen invalidates the pardons granted to his son Hunter, his brother and 37 death row inmates.

Biden’s team insists he was aware of every decision, and there is no evidence he used an autopen to sign pardons. But for Trump, the mere use of the device casts doubt not just on Biden’s signatures, but on his mental fitness as a whole.

A simple-looking machine with a long history

The autopen that sparked this political firestorm appears innocuous, but its history predates even the steam engine. The story begins in 1803 with British-American inventor John Isaac Hawkins, who created the polygraph—not the modern lie detector, but an early pantograph. In this machine, one pen wrote a message while a second pen simultaneously reproduced it.

Thomas Jefferson, the third U.S. president, was fascinated by the technology. He bought two units—one for the White House and another for his Monticello estate. In a letter to painter Charles Willson Peale, Jefferson wrote: “I cannot live without the polygraph.”

But the polygraph still required the writer’s physical presence. It couldn’t sign by itself. That breakthrough came in the 1930s, with the development of the “robot pen”—a machine resembling a cross between a turntable and a music box. It recorded the motion of a person’s hand, like a conductor writing music, and stored it on a “signature disc,” similar to a vinyl record. A mechanical arm could then replicate the movement with ink.

The next major leap came in 1942 when inventor Robert M. De Shazo Jr. responded to a request from the U.S. Navy and began producing the first official government autopens. Soon, machines were installed in senators’ offices, congressional buildings and eventually the White House. By the 1960s, about 500 autopens were operating in Washington, including in high-security locations, helping officials sign thousands of documents—telegrams, letters, judicial appointments—without lifting a finger.

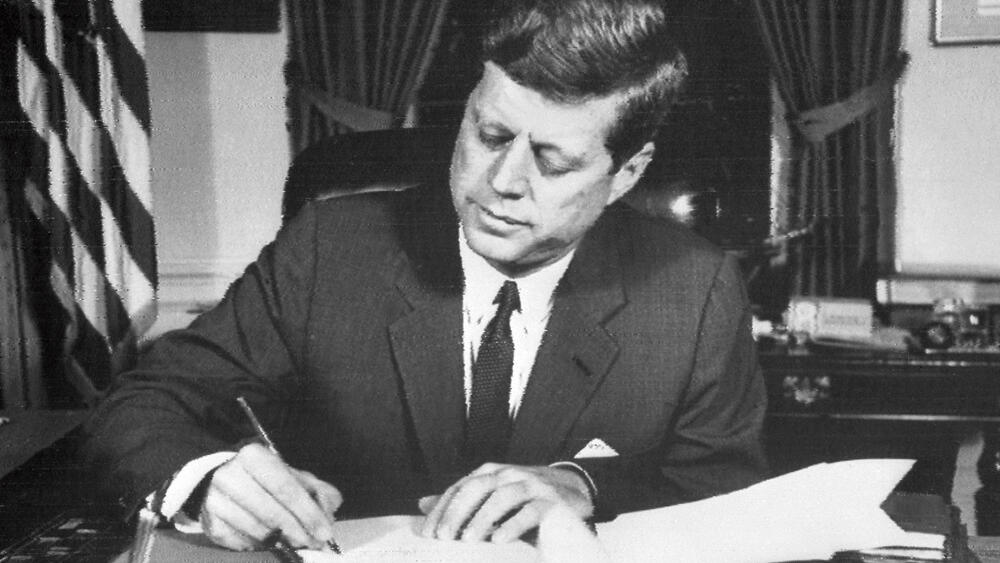

While President Harry Truman is believed to have used the autopen for routine documents, it was Lyndon B. Johnson who brought it into the public eye, allowing journalists to film it in action. The National Enquirer ran a story titled: “The Robot That Sits in for the President.” Johnson’s predecessor, John F. Kennedy, was such a devoted user that his actual signature became a collector’s rarity. Though he cut back on autopen use during his presidency, the reputation stuck, and a book titled The Robot That Helped to Make a President cemented the myth.

Modern autopens: High-tech precision

Today’s autopens are digital machines. Companies like Maryland-based Damilic Corp, led by engineer Bob Olding, produce the most advanced versions. Olding is considered the autopen world’s undisputed guru, partly because he’s among the few willing to speak publicly about how the device works. His models store encrypted signature data on SD cards and use robotic arms to reproduce every micro-movement of the original signer’s hand.

The device can hold any standard commercial pen—even Sharpies, favored by George W. Bush for their “presidential” look. Though the pressure is uniform and the result detectable to the trained eye, the signature is so accurate that it’s nearly impossible to distinguish from the real thing without close analysis.

In 2005, the autopen raised a practical question. President George W. Bush was at his Texas ranch when a critical federal bill needed his signature, and time was running out. The White House asked the Justice Department for a formal opinion: Could the president legally sign legislation via autopen, remotely?

The DOJ ruled that Article I, Section 7 of the Constitution—requiring the president to “approve and sign” a bill—didn’t demand a literal, physical signature. As long as the president gave informed, explicit authorization, an autopen signature was valid. Still, Bush ultimately flew back to Washington and signed the bill in person, reinforcing the symbolic value of human presence.

From Obama to Biden—and beyond politics

President Barack Obama embraced the autopen. In 2011, during a G8 summit in France, he became the first president to use one to sign federal legislation—an extension of the Patriot Act. He later used it to sign a budget bill while visiting Indonesia, another during his vacation in Hawaii, and in 2013 to extend the Bush-era tax cuts.

Biden also used the device, most recently in 2024 while in San Francisco, to authorize emergency funding for the Federal Aviation Administration and prevent a regulatory shutdown as Congress debated the long-term budget.

But the autopen’s reach extends far beyond politics. Celebrities, authors and musicians use it to cope with the avalanche of autograph requests. Canadian author Margaret Atwood developed her version, the LongPen, which allows for video chats and real-time book signings from afar.

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

Yet when the public finds out, reactions are often less than friendly. In December 2022, Bob Dylan released a signed edition of The Philosophy of Modern Song at $600 per copy. Fans quickly noticed the signatures were too similar. Within days, it was revealed they were produced by an autopen. Dylan issued an apology, the publisher offered refunds, but the reputational damage stuck. Dylan said COVID restrictions and vertigo prevented him from signing personally.

Former Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld faced backlash in 2004 when condolence letters to fallen soldiers’ families were revealed to have been autopen-signed.

A legal gray area

Despite the growing use of autopens, the legal status remains ambiguous. The DOJ’s 2005 opinion supports their use, as long as the president gives prior approval. But the courts have never issued a definitive ruling.

Some legal scholars argue the core issue isn’t the use of technology, but the president’s absence during the act of signing. Just as delivery services require a signature in person, traditional legal doctrine emphasizes the importance of presence. When someone isn’t there, physically or consciously, the validity of their act may be questioned.

This is the heart of Trump’s current argument: if Biden wasn’t alert, fit or even aware of the decisions the autopen was executing, then the documents themselves might not be valid. Biden’s allies firmly reject this, saying he was fully briefed and responsible. Still, until the courts rule, the doubt lingers.

Former U.S. Attorney John Fishwick Jr. said in an interview: “Constitutionally, a pardon doesn’t even have to be in writing. The president can pardon someone orally. But still, it feels wrong to use an autopen for something so serious.”

In 2024, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals in Virginia touched on the issue. It ruled that a presidential pardon does not have to be written, weakening the legal foundation of Trump’s challenge. While the case didn’t involve the autopen directly, it emphasized that the president’s intent, not the method of execution, is what counts.

And yet, Trump continues to insist that this is not just about signatures. It’s about who signed—and whether that person was present, in body or at least in mind. Ultimately, this investigation may not be about a robotic pen, but about the competence of a president.