Rian Johnson’s Knives Out series is a clear and recurring example of the gap between what a film promises and what it delivers. On paper, it is hard to complain about a franchise built around detective Benoit Blanc (Daniel Craig), who continues a long tradition of eccentric sleuths with razor-sharp instincts. These films are meant to be sophisticated genre entertainment with plenty of twists — yet each entry ends up less than the sum of its parts.

Six years have passed since Knives Out, which cost $40 million and brought in an impressive $312 million. Its success prompted Netflix to open its wallet and pay a staggering $496 million in 2021 for two sequels. That funding made it possible to craft two more lavish detective comedies with star-studded casts: Glass Onion (2022) and now the third film, Wake Up Dead Man: A Knives Out Mystery. Johnson has repeatedly said he is willing to direct more. It is easy to see why.

Watching these films, you can sense the enjoyment Johnson finds in creating outlandish characters and twist-heavy mysteries. American critics are largely enthusiastic, but to my mind, the effort to produce polished entertainment runs into a gap between the franchise’s production resources and its script shortcomings. Johnson’s ambition to use these stories as vehicles for political satire is admirable, but the predetermined stance often flattens the mystery’s resolution.

Knives Out, the most refined of the three, centered on class conflict. The wealthy white family of the murdered author was an assortment of entitled, greedy characters — contrasted with a devoted Hispanic nurse physically incapable of lying without vomiting. Glass Onion skewered Silicon Valley’s billionaire “tech bros.” In Wake Up Dead Man, the central figure is a monstrous preacher used to critique authoritarian leaders who weaponize religion to spread hate and consolidate power. It isn’t hard to see where the satire is aimed.

Wake Up Dead Man is not short — nearly two and a half hours — and its first 40 minutes unfold without Blanc, the series’ central figure. This stretch is devoted to the events leading up to the murder that must be solved. The narrator is a young priest, Jud Duplenticy (Josh O’Connor), who effectively functions as the film’s protagonist. A former boxer who quit the sport after injuring someone, he now offers spiritual support but still has moments where the fighter resurfaces — such as when a deacon says something “unbearable” (the film spares us the details), prompting Duplenticy to break his jaw with a punch.

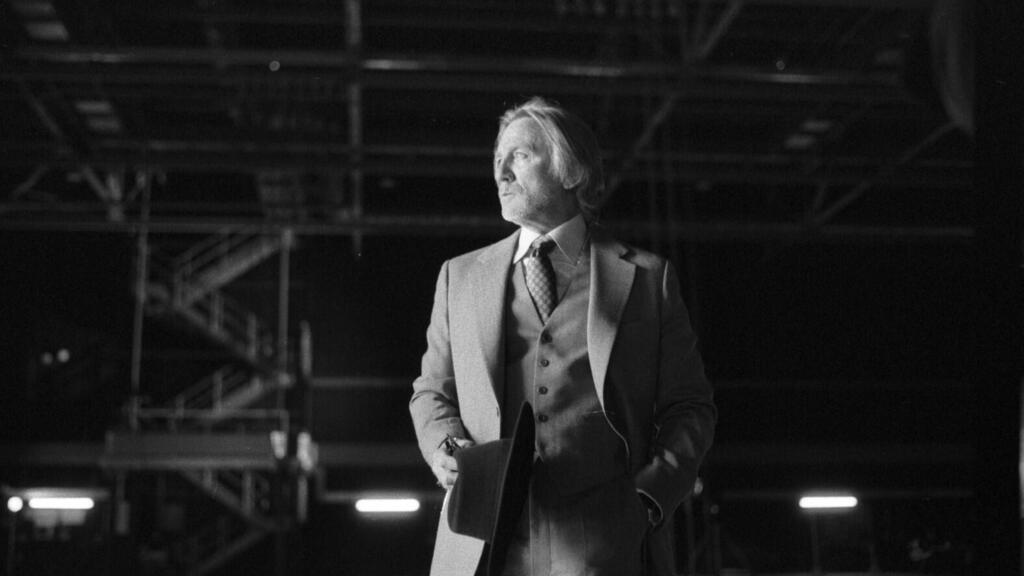

He would have been expelled from the church were it not for the backing of Bishop Langstrom (Jeffrey Wright). In exchange for that protection, Duplenticy is sent to a troubled small community in upstate New York to serve as an assistant priest. The senior cleric there is Monsignor Jefferson Wicks (Josh Brolin), a charismatic and violent priest who preaches fear and anger rather than love and compassion. The parish also carries decades-old secrets tied to its founding priest’s family and a large sum of missing money. The detailed recounting of events from long ago — seemingly disconnected from the impending murder — practically hands the audience the motive in advance.

Wicks’ small congregation includes characters played by respected actors. Glenn Close portrays Martha Delacroix, a devout believer who manages every aspect of the church from finances to laundering the monsignor’s vestments. Close brings layers of complexity to a woman whose pure faith clashes with the church’s sordid reality, but even she is not given enough screen time to fully develop. The secondary characters fare worse.

Kerry Washington plays Vera Draven, a successful attorney linked in a murky way to the parish’s past scandals. Her adopted brother, Cy (Daryl McCormack), is a conservative, struggling politician chasing relevance on social media. Andrew Scott (Sherlock) plays a writer whose star has faded. Cailee Spaeny (Priscilla) is a wheelchair-using cellist whose career ended due to health issues. Jeremy Renner plays the town doctor, Nat Sharp, and Thomas Haden Church portrays Samson Holt, the church caretaker. These characters are underwritten to the point that it’s hard to understand why they orbit the unpleasant monsignor at all. A strong cast paired with thin characters only highlights the script’s weaknesses.

One bright spot is the chemistry between Craig’s Blanc and O’Connor’s Duplenticy, strengthened by the way the young priest becomes a sort of apprentice — despite their very different views on faith. Their exchanges carry the film’s main discussions on belief, though raising these themes does not guarantee depth. The movie tries to be more serious than the previous installments, exploring faith, power and corruption, yet it still wants to be funny and light. The balance doesn’t always hold.

As the film progresses, its flaws become more apparent: too many scenes of people talking in rooms, too many clues that lead nowhere and too many forced twists. Perhaps structuring the film as a three-part miniseries would have helped refine the material or at least establish a sturdier narrative frame. As it stands, the finished film feels like it needed another draft or two to reach its full potential.