Ayat, the Palestinian restaurant that stirred New York when it launched a menu titled “From the River to the Sea” shortly after the October 7 Hamas massacre, is once again at the center of a storm. The spot, founded in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, became both a symbol for its supporters and a lightning rod for its critics. Now it is expanding to Manhattan’s Upper West Side—a neighborhood where roughly 30% of households are Jewish and within walking distance of Columbia University, the epicenter of pro-Palestinian protests in the U.S.

For many residents, the move feels like a provocation, reigniting debate over the limits of free expression in a city where even restaurants have become front lines in the Gaza war.

The owner, 32-year-old Abdul Elenani, a Brooklyn native and son of Egyptian immigrants, insists the new branch will not be just another falafel stand. “It’s not just food,” he told local media. “It’s an attempt to bring people together and send a clear message about Palestine.”

He has pledged free meals to Columbia students who take part in pro-Palestinian demonstrations and says the restaurant will host fundraisers for Gaza residents as well as for the campaign of anti-Israel City Council candidate Zohran Mamdani.

Elenani has already provided more than 9,000 free meals to volunteers working for the Democratic lawmaker’s campaign, and he plans to continue the tradition of Shabbat dinners open to the public—events that have drawn more than a thousand participants, including many Jews.

Elenani, a construction contractor turned restaurateur, named the place after his wife, a 35-year-old lawyer of with East Jerusalemite parents who is known online as an expert in Palestinian cuisine. Ayat quickly gained glowing reviews and a loyal clientele.

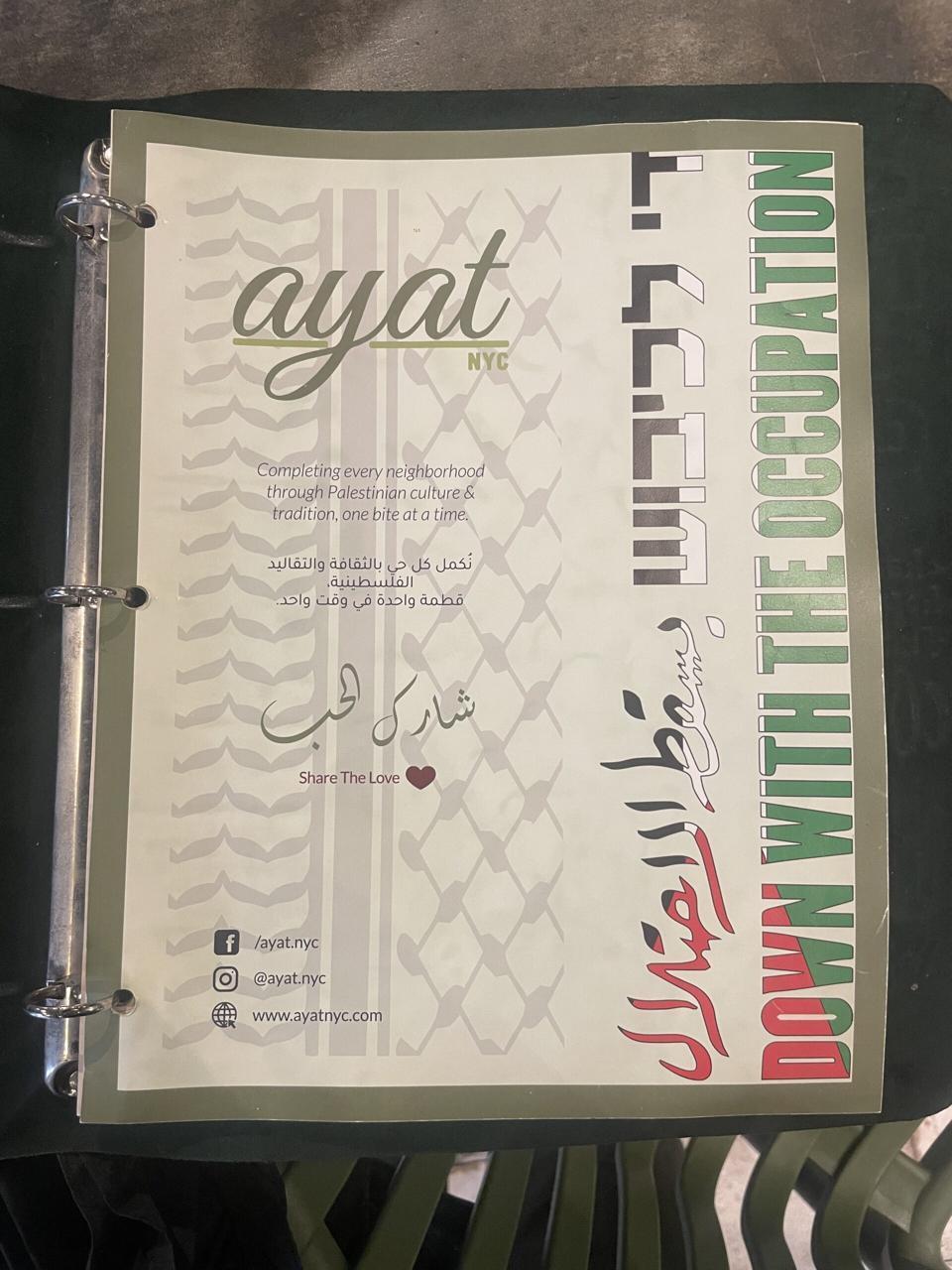

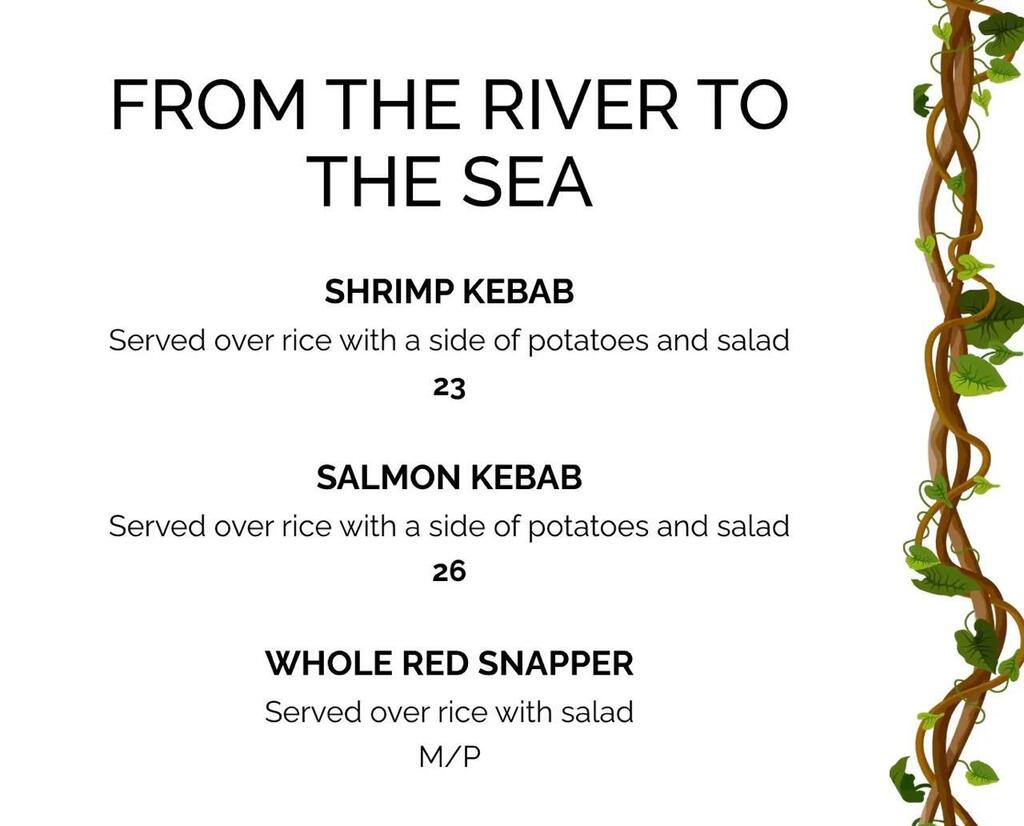

But along with the hummus came the slogans: “End the Occupation” printed in three languages on menus, murals of Palestinian women in red and green, and takeout bags stamped with “Universal Brotherhood” messages such as “Jews, Muslims, Christians—we are all human beings and we love you.” The launch of the “From the River to the Sea” menu—featuring shrimp, red snapper, or salmon—just days after Hamas massacre, brought Ayat straight into New York’s polarized cultural-political arena.

Jewish groups like the Anti-Defamation League and the American Jewish Committee condemned the use of the slogan, long associated with calls to eliminate Israel. “I am not going to apologize for what we represent,” Elenani responded. Online debate quickly escalated into real threats.

Owner Elenani pledged free meals to Columbia students who take part in pro-Palestinian demonstrations

The restaurants suffered break-ins and vandalism, their Instagram accounts were flooded with fake one-star reviews and insults, and the Bay Ridge branch’s phone line had to be disconnected after dozens of daily threats. In one call, a voice said: “We Jews are coming for you!” In another: “We’ll blow up your place tomorrow.”

On another occasion, a man entered the restaurant and called the staff “terrorists.” Police were forced to station patrol cars outside, and Elenani admitted his wife feared leaving home with their newborn. Still, he stood firm: “From the river to the sea is not a call for Israel’s destruction, but for equality.” To reduce risks, he plans to reveal the address of the new branch only once renovations are complete, likely in December.

Ayat is not unique. Official New York State data show a sharp rise in hate crimes against Jews since the start of the war, matched by a rise in crimes against Muslims. Both Israeli and Palestinian restaurants have become flashpoints. In this climate, Ayat’s new Upper West Side location looks particularly combustible. Since October 7, Columbia has seen daily protests, clashes with police, and campus building takeovers. Elenani’s pledge of free meals for demonstrators is seen by many as more than a business move—it looks like the establishment of a political outpost in the heart of a “Jewish” neighborhood.

“This isn’t a business, it’s a political headquarters disguised as a restaurant,” says Danny, a former Israeli now living on the Upper West Side. “They’re putting it right in our faces, in our neighborhood, while our kids go to Jewish schools here.”

Another resident, a mother of three, adds: “I don’t want my children walking past a place with anti-Israel slogans on the walls. It feels like a direct threat.” Others are already calling for a boycott, and one warned: “If the city doesn’t shut it down, we’ll make sure it won’t stay open long.”

Elenani, for his part, repeats the same mantra: “I’ll make them come closer to me. I’ll do everything to make people feel comfortable.” But between declarations of reconciliation and flames on the street, the gap is narrow. In a neighborhood where even a single poster of hostages—or a mural—has ignited confrontation, the opening of Ayat’s new branch seems like a recipe for another inevitable storm.