By eye or with a measuring cup, one‑to‑one or sticky — everyone is loyal to their rice. Every day, more than half of the world’s population eats this same grain. It grows on almost every continent, is considered one of the three largest agricultural crops in the world, and holds a central role in the food security of entire countries. Rice is indeed perceived as a simple ingredient, but behind it hides a story of culture, agriculture and eating habits.

In Israel, rice is a permanent resident in the kitchen: it appears in everyday and festive meals, as a main dish or as a side. It is both ethnic and cultural, and at the same time a simple familiar food, one that doesn’t always excite. Every household has “our” rice. Some swear by basmati, others prefer Persian; some choose brown, others round grain, and some keep the same brand for years and refuse to switch.

The taste also varies: some like it white with salt only, others season it, and some add spice blends. Sometimes it is served as a vegetarian dish and sometimes based on meat. The method of preparation is also a subject of debate: some measure the rice‑to‑water ratio strictly, others work “by eye,” some sauté first in oil and others soak in water before cooking. And yet, maybe we don’t know enough about it. What are the different types of rice, what is the difference between them, where does it come from, and how is it cooked correctly? We went out to check.

Indica or Japonica? The guide to rice families

There are hundreds of types of rice in the world. They are divided into different families and varieties, and most of the rice eaten in the world belongs to two subspecies of the same plant: Indica (long, thin grains that separate after cooking) and Japonica (short or round grains, more starchy and tending to be sticky).

Indica is common in South Asia and the Middle East and includes varieties like basmati, jasmine, Persian, and various red and black rice. Japonica is common in Japan, Korea and Italy and includes round grain rice, sushi rice, and risotto varieties like Arborio, Carnaroli, and Vialone Nano.

But beyond the scientific classification, in the kitchen we are mainly looking for the exact taste and texture for a dish. To set things in order, here are the identity cards of the familiar types and the culinary pairing that suits them.

Basmati is characterized by a long, thin, aromatic grain that remains separate and airy. It requires a good rinse and sometimes soaking, and is cooked in water or by steaming. It is especially suitable for curry dishes, Indian and Persian meals, or as classic white rice.

Jasmine is long and fragrant but softer than basmati and slightly sticky. It requires less rinsing than basmati and a slightly lower water ratio. It is suitable for Thai food, stir‑fries, and Asian dishes.

Persian rice is a general name for a family of varieties from Iran. It is aromatic, delicate, separate, and sometimes slightly oily. It usually requires rinsing and soaking and cooking in the traditional method (plenty of water and then draining or steaming). It is suitable for festive stews and as a side to meat and chicken.

Round grain rice has short, starchy grains and tends to stick. It requires less rinsing and a precise water ratio. It is suitable for sushi, sticky rice, stuffed vegetables and rice patties.

Risotto rice (Arborio, Carnaroli, Vialone Nano) is very starchy and creates a creamy texture. The cooking method is different and includes gradually adding hot liquids while stirring.

Brown rice (whole grain) is any variety from which the husk and bran have not been removed. Its taste is nutty and its texture chewier. It requires more water and longer cooking time, and is suitable as a healthy side, for grain bowls and warm salads.

Red brown rice is a whole grain with a naturally reddish husk and a deep, nutty flavor. It requires long cooking and sometimes soaking.

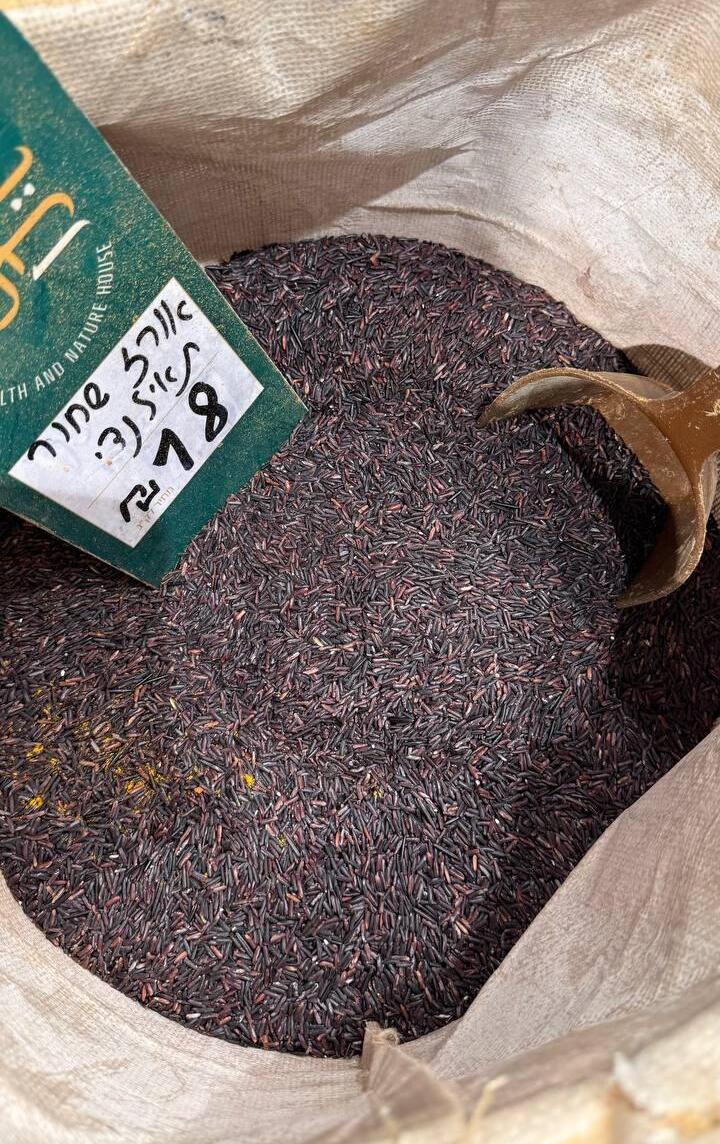

Black rice is an ancient variety with a dark husk, a sweet‑nutty taste, and a chewy texture. It requires long cooking like brown rice and is also suitable for Asian desserts.

Wild rice (literally wild) is actually a different plant (Zizania). It is long, dark, tough, and chewy, requires much longer cooking with plenty of water, and is suitable for blends and festive dishes.

Myth or real danger? The truth about arsenic in rice

Arsenic is a natural element found in soil, water and air, and therefore it reaches food through the ground and irrigation water — both in conventional and organic agriculture. It is impossible to avoid exposure completely, because almost all plants absorb it to some degree. Rice absorbs relatively high levels because it is grown under flooded conditions, and it usually contains more arsenic than other grains (especially brown rice, since the compound accumulates in the husk).

Various tests have shown large differences between products, with no evidence of immediate danger but also without certainty regarding the long‑term effects of high consumption. Washing rice reduces only a small portion of the arsenic and its effect is limited. Cooking in a large amount of water and pouring it off at the end reduces the arsenic much more significantly, but the vitamins are also washed away this way. The solution is not to give up rice, but to vary and balance, and those particularly concerned can occasionally choose the cooking method with lots of water and draining.

Understanding our consumption habits

To understand our rice consumption habits, we visited the spice shop Ras el-Hanut in Jerusalem. Owner Miri Cohen‑Chaim showcases a variety of some 10 types — from basmati and Persian to black wild rice.

Which type of rice do Israelis connect with most? “The rice people love to buy most in Jerusalem is jasmine rice,” says Cohen‑Chaim. “It’s most suitable for anyone cooking authentic foods — alongside kubbeh, inside stuffed vegetables, rice and beans. It’s the best‑selling and most popular rice. In addition to loose rice, we also have it in five‑kilo rice bags, which suit large families, alongside bags of basmati, round grain and Persian.”

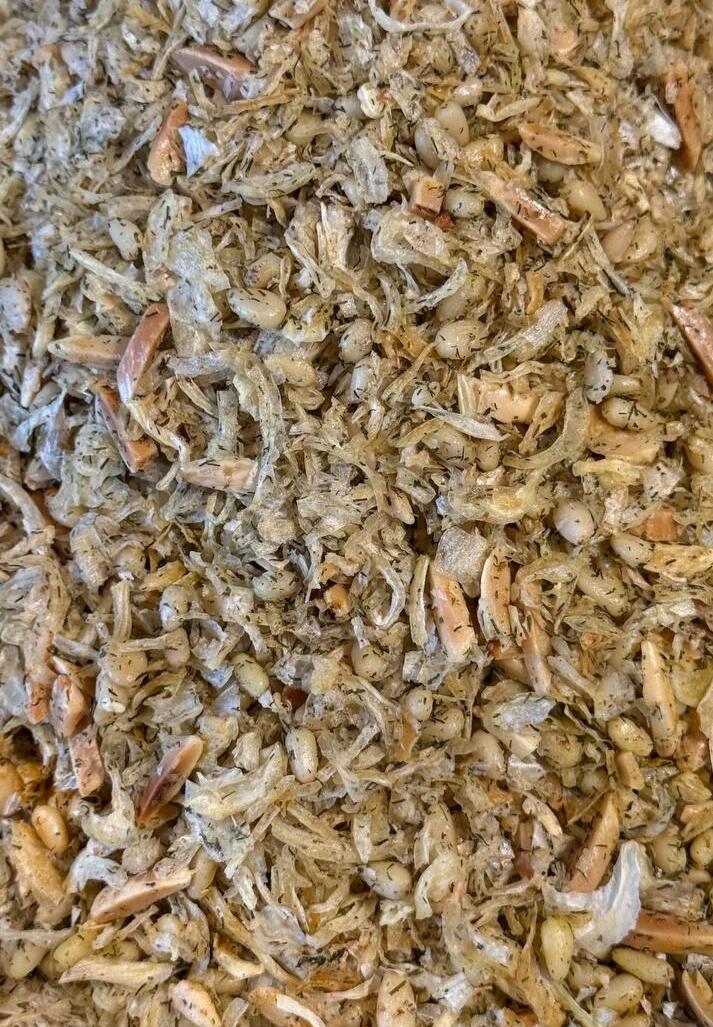

How do you upgrade rice? “There are blends that you add to the pot at the beginning of cooking — they give flavor and each blend takes you in a different direction. It really upgrades it. The ratio is 1:3 — one third cup rice and two thirds blend.”

The price range in the store is wide: the lowest price is for Persian, jasmine or round rice at nine shekels per kilo. In contrast, the most expensive rice is black wild rice, sold at 65 shekels per kilo — a luxurious rice rich in vitamins and minerals mainly used in chef restaurants.

Common mistakes and tips for perfect rice

“Rice is two things. First of all, it’s the best stage a cook could have,” explains Zakai Houja, chef and owner of Jacko Street and Super Hamizrah in Jerusalem. “It’s really a basic product yet so rich that you can show who you are with one product. Second, it’s roots. Go to any home, taste the rice — whether grandma made it or mom — and you’ll understand the roots of the person, who they are and how much they belong in the kitchen. That’s the best definition of rice — it’s a product to impress with.”

Which types do you use? “Let’s differentiate — there’s restaurants and there’s home. In restaurants, every rice has its role. Round grain rice goes to stuffed dishes at Jacko, Japanese rice (which is also round but suitable for sushi) goes to Super Hamizrah. At home I usually go with Persian rice.”

What is your rice‑cooking method? “It depends. If you’re making schnitzels and Arabic salad you want plain rice — simple, white and clean. If it’s Shabbat rice, you want it ‘pachila’ (in Kurdish: sticky/porridge‑like), like porridge with the sides slightly burnt and everything juicy. There’s no rule that rice needs to be one way, period. Everyday? I don’t rinse rice. I take Persian white rice, two cups of rice, three cups of water, the simplest. A little frying, boiling water and don’t open for 18 minutes. Peace and goodbye.”

How would they prepare it at your house? “My grandmother, may her memory be a blessing — God knows how she used to do it. She would open the lid 80 times, add cold water every time she felt like it, and her rice came out rare. But those are skills that aren’t in our generation. My mother uses Persian or jasmine. Grandma was fixated on jasmine and sometimes mixed round grain for stuffed vine leaves.”

What are the most common mistakes people make? “In the end, rice — because it’s so basic — needs to be understood. Once you rinse rice it absorbs water, and if you don’t take that into account when calculating liquids — you get porridge or broken rice. Also, vegetables like mushrooms release liquids and you need to account for that. Another mistake is opening the pot and stirring all the time. As for working ‘by eye’ — you need high skills for that, and in general it’s better to measure. Another common mistake is with pot size and flame: once I saw cooks put a small pot on the largest flame, and that’s not good.”

So what are the tips for perfect rice? “Always weigh or measure by volume with the same cup (or by weight ratio of 200 grams rice to 300 grams water). Boiling water is a must, because cold water changes the balance. You put spices and salt at the beginning with the oil. Add sautéed onions and mushrooms a minute before the end, stir, and let the rice rest. At the end of cooking close the lid for 15 minutes — don’t eat right away. Only when it’s ready, open it and fluff with a fork. And one small tip: a rib of celery, thyme, or garlic adds body to the rice. For me, a celery rib is a constant. And when the rice is ready squeeze a bit of lemon on it and mix — it’s amazing.”

The health perspective: fiber, sugar and storage

After all the conversations about taste, texture and cooking methods, the health question arises: is there a real difference between the types, and what is rice’s effect on blood sugar levels? There’s also the practical side — how to store cooked rice safely. Karen Ann Gaiman, dietitian and fitness coach, puts it in order for us.

What are the advantages of different rice types? “In white rice, especially basmati, there is a substance called ‘resistant starch’ that functions as dietary fiber and gives a more moderate rise in blood sugar. Brown rice contains more fiber and nutrients in the husk, but it also absorbs more metals, so it’s recommended to wash it with about six cups of water before preparation. In colored rice, like red, the husk contains antioxidants, which is an additional advantage.”

Who should limit consumption? “Rice breaks down fairly quickly into sugar and causes a high glycemic response, so people with diabetes or a tendency toward diabetes should think twice before consuming large amounts. You can moderate the sugar rise by combining with fat (like almonds) or legumes. Rice is an excellent base for experimenting with legumes — mejadra with lentils, peas or chickpeas. Legumes have the advantage of fiber that is friendly to gut bacteria, and more protein.”

How to store cooked rice? “Cooked rice is kept in the fridge in an airtight container for three to five days (a vacuum container will maintain freshness better). If it changes color, shows mold or smells odd — there’s no choice but to throw it out. You have to remember that rice can be frozen; it freezes reasonably well, and if you want to prepare a large amount and freeze in portions, it’s an excellent solution that keeps for a long time.”

How to incorporate it properly in a diet? “You have to remember that rice belongs to the carbohydrate family, so the amount depends on personal goals. The most important thing is to vary — combine different types, maybe also crisps or rice sheets, and make sure we gain nutritional value from a variety of carbohydrates and not just eat rice all day.”

First published: 15:01, 01.26.26