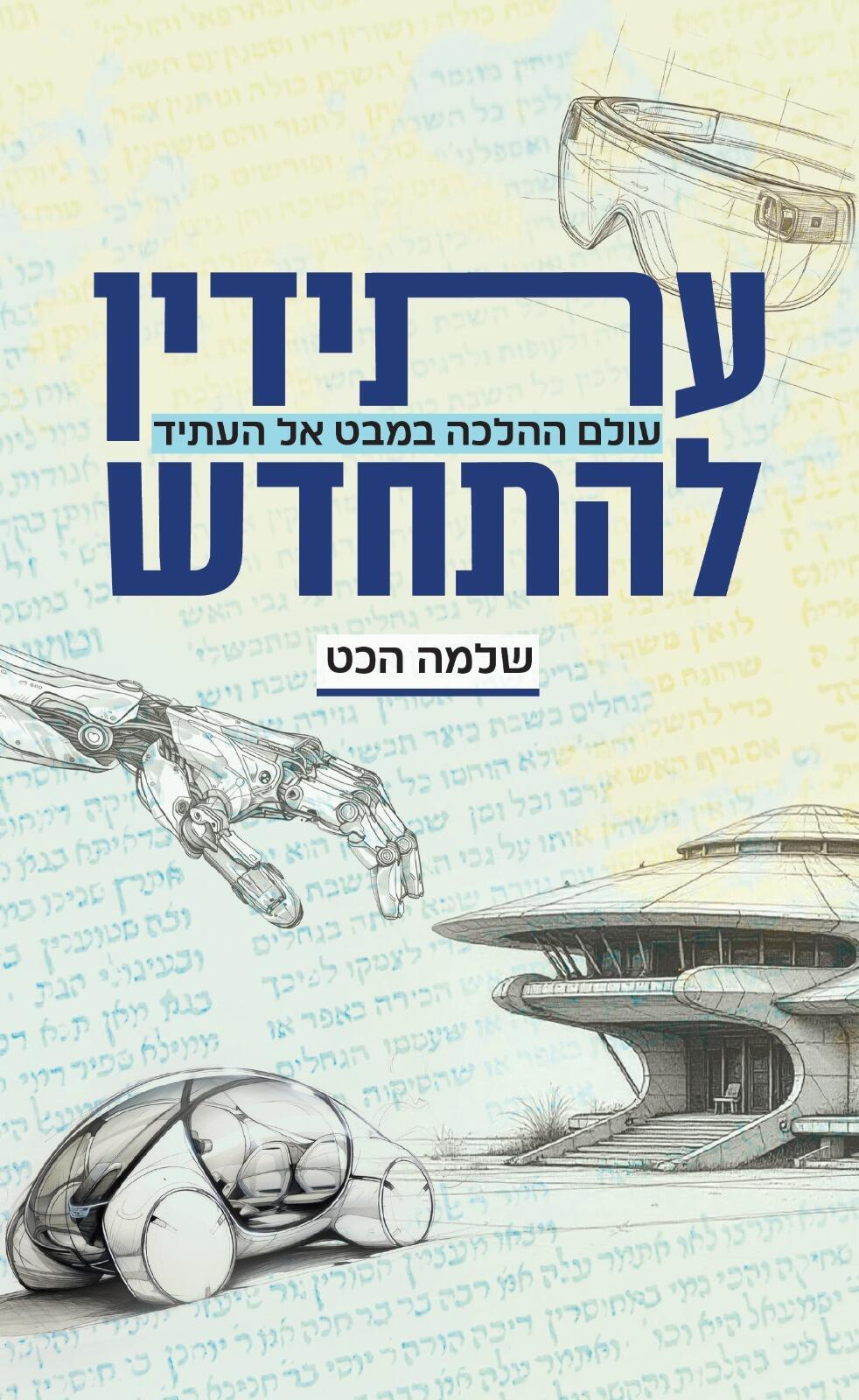

When Rabbi Shlomo Hecht began writing a book four years ago examining what Orthodox Jewish law and Judaism might look like in 20 to 30 years, he decided to include a chapter titled ‘Halachic applications of artificial intelligence.’ At the time, the central question sounded entirely science-fictional: could Jewish legal rulings be issued by computerized systems?

After the dramatic revolution sparked over the past year by ChatGPT and similar tools, it is now fairly clear that the answer is yes, subject to various limitations. As a result, the chapter remains in Hecht’s new book, Atidin LeHitchadesh (Yedioth Books, edited by Dr. Chayuta Deutsch), but the question has shifted. It is no longer whether such rulings are possible, but whether there is a problem with them and whether they would be considered valid.

5 View gallery

AI. 'Halachic language will not succeed in keeping pace with technological development, and we need to prepare for that'

(Photo: Shutterstock)

Addressing more conservative rabbis who fear what lies ahead, Hecht offers a reminder. “In the past there was criticism of halachic questions answered via text messages, but that actually increased the number of rabbis dealing with these issues. I believe that when it comes to artificial intelligence, rabbis simply will not be able to compete.

As someone who answers halachic questions myself, I also attach importance to the idea of ‘siyata dishmaya,’ divine assistance, for a rabbinic decisor. But the possibility that AI will issue rulings is a near-term forecast, and it could change the entire world of study and Jewish law."

What is your overall assessment?

“The conclusion that emerges from the book is that halachic language will not succeed in keeping pace with technological development, and we need to prepare for that."

Concern about harming the spirit of Shabbat

Hecht, 54, married and a father of six, lives in Petah Tikva. He is trained as an economist and software engineer, and alongside his professional work he was ordained as a rabbi. For two decades he has dealt with issues of Jewish law, the public sphere and technology. He is active in the Tzohar rabbinical organization and in various rabbinical forums, and was among the early members of the Beit Hillel organization of rabbis and rabbaniot, known for relatively lenient halachic positions, a stance that drew public criticism within the religious Zionist community.

5 View gallery

Rabbi Shlomo Hecht: 'We will need to find a new language for Shabbat, an educational and philosophical one'

(Photo: Arye Minkov)

Is the fear of being labeled overly lenient the reason your book mainly analyzes issues rather than issuing concrete rulings? Were you worried about ‘what people would say’?

“First of all, even in Beit Hillel people worry about what others will say, which is why I sign the book in my own name and not as part of any group. Second, among the ultra-Orthodox the fear of public reaction is several levels higher. Still, those who worry about what people will say will discover that the public moves forward on their own."

We saw this during the war, when some in the religious Zionist community were not embarrassed to update news on Shabbat inside synagogues.

“There is an entire chapter in the book devoted to Shabbat. At the start of the previous century, the attitude toward electricity on Shabbat reflected the fact that operating an electrical device required physical effort and caused sparks. Most devices produced heat and noise, and the result was visible and loud, accompanied by prohibitions from the Torah.

Today, with autonomous vehicles, for example, those prohibitions largely disappear. Still, I cite Rabbi Yaakov Ariel, who wrote in the past: ‘An unworthy student could distort the law and, Heaven forbid, permit travel in such a car on Shabbat. In my humble opinion, traveling in such a vehicle is a desecration of Shabbat. It borders on outright Torah prohibitions and is forbidden mainly because of the severe harm it causes to the holiness of Shabbat.’”

Rabbi Ariel even suggested considering a step backward and banning the use of ‘electrical automation'.

“First of all, he makes a clear distinction between permitting an electric mobility scooter for the sick or elderly and permitting use by the general public. During the war, distinctions were also made and the use of electric vehicles to get to and from shifts was permitted far more easily. In the future, permitting autonomous vehicles will be even easier.

"I think Rabbi Ariel is mistaken because he does not take into account that the day is not far off when the level of sacrifice of everyday routine demanded on Shabbat under his approach will be too great, and the public will find it very difficult to comply.

“Even when you try to examine what the real prohibition is in using a mobile phone on Shabbat, it is extremely hard. No electrical circuit is being opened or closed, and there is no mechanical switch involved. There is certainly no Torah-level prohibition, and even the rabbinic prohibition is limited. The main concern is damage to the spirit of Shabbat."

What will make observing Shabbat especially difficult in the future?

“Density in Israel will leave no option but living in high-rise buildings, in smart homes that control lighting, climate, water and more. Devices of various kinds ‘understand’ and ‘learn’ their surroundings and initiate actions on their own, without human touch. In such a world, the level of prohibition involved in operating electrical devices drops dramatically. We will need to find a new language for Shabbat, not a halachic language but an educational and philosophical one."

5 View gallery

Women praying outdoors during COVID. 'The pandemic accelerated change'

(Photo: Moti Kimchi)

In the past, were there rabbis who dared more easily to innovate or be lenient?

“Ultra-Orthodox rabbis are often more lenient than religious Zionist rabbis when asked a personal question not intended for publication. Beyond that, in the past leading rabbis recognized the halachic need for innovation and the fact that the public also made decisions on its own. For example, in many European communities the question of who would say Kaddish caused conflicts. In Israel this has almost disappeared, for a very simple reason: the adoption of the Sephardic custom in which several people say Kaddish together, and rabbis were forced to accept it.”

The change brought by the COVID pandemic

Hecht calls on rabbis to lead change rather than be dragged behind it. As an example, he cites ultra-Orthodox Rabbi Asher Weiss, one of the leading decisors of the current generation, who chose to approve and encourage "Minyanei Hatzerot" (holding home prayer quorums) during the COVID period.

“He permitted these prayers even though, contrary to halachic requirements, the worshippers were not in one place and could not see one another. He feared the spread of the pandemic if the ultra-Orthodox insisted on praying inside synagogues,” Hecht explains.

Hecht adds that “the public’s desire to pray together even during a pandemic, and the rabbis’ desire to maintain communal prayer rather than tell people to pray alone at home, led me to write a special chapter in the book examining whether it might be possible to go a bit further and allow a synagogue with holograms. That is, you sit at home and see the worshippers in the synagogue, as well as those at home who are connected as holograms. Would that count as a Minyan (a quorum of 10 adult men) prayer?"

And your conclusion?

“I think there still needs to be a synagogue with at least 10 people physically present, joined initially by the sick, the elderly or soldiers. But this is not a ruling for today, it is a forecast for the future.

What is clear is that changes around us, including the coronavirus, are accelerating a situation in which women will be included in a Minyan quorum as well as in Torah reading. Rabbi Yitzhak Yosef recently noted in his bulletin that the Talmud in Tractate Megillah states regarding Torah readings: ‘All may be counted among the seven, even a minor and even a woman.’ Rabbi Yosef opposes this in practice, but he acknowledges that in principle there is a halachic basis for women being called to the Torah and even reading from it."

What else is expected in the future?

“The shift to using cultured meat and dairy products produced in laboratories. This will happen relatively quickly, and then there will no longer be a prohibition of mixing meat and milk. We will need to discuss writing Torah scrolls, tefillin and mezuzot on cultured parchment, and even the renewal of sacrificial offerings.

"What all these discussions share is the urgent need to begin preparing for a Judaism very different from the one we have known for the past 2,000 years. It will be a Judaism that is primarily intellectual and faith-based, with halachic engagement playing a secondary and ancillary role. Bottom line, I am very optimistic and look to the future with hope."