Several weeks before Somaliland made headlines following Israel’s historic recognition, two Chabad-Lubavitch Hasidim from Miami were already there on an unusual mission: printing an ancient Jewish text. Attorney Mendy Lieberman and businessman Yanki Rubin, members of the Chabad community in Florida, traveled to the African territory not to tour, seek business opportunities or join an official delegation, but to print the Tanya, a foundational Hasidic work.

In an interview with the Chabad newspaper Kfar Chabad, they said this was part of an unconventional personal mission: entering countries considered sensitive or hostile to Israel and attempting to print the Tanya there. They have done so in Iraq, Kuwait, Somaliland and South Sudan.

The Journey to Print the Tanya in Somaliland

( Video: Courtesy)

“There are about 195 countries in the world,” they said. “There are apparently no more than 15 where the Tanya has not yet been printed. Very few people have the courage to travel to dangerous places like these to fulfill this directive.”

What is the Tanya?

The Tanya, written more than 200 years ago by Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi, founder of the Chabad-Lubavitch movement, is still studied as a psychological and spiritual guide addressing inner struggle, meaning, choice and emotion. Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson viewed it as a universal work and insisted it be printed wherever possible, even in remote or unwelcoming countries. The book has been printed in Iran and Lebanon, including during the First Lebanon War; copies from that printing are displayed in the office of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. In recent years, it has also gained popularity among nonreligious Israelis.

Printing the Tanya in Somaliland was far from simple. Rubin said they encountered deep suspicion from local printers even before arriving. “When you want to print the Tanya in another country, especially in a place like Somalia or Somaliland, it is not welcomed,” he said. Nearly every print shop refused. “Everyone was afraid,” he added. Only after prolonged questioning, additional payment and what they described as the Rebbe’s blessing did one printer agree.

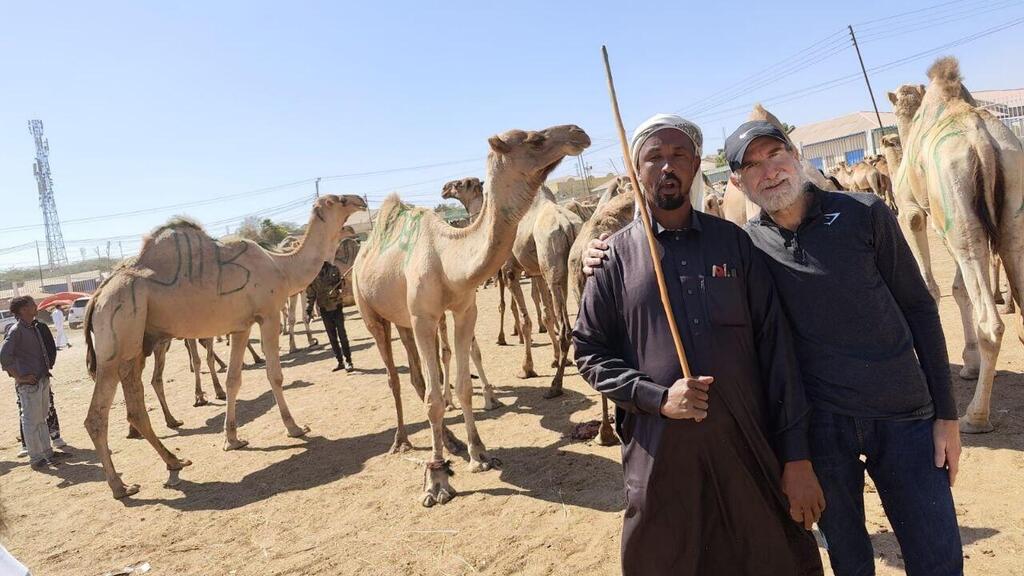

Their stay was also challenging. “People looked at us as white American tourists,” the two said, noting there are few foreigners in the streets of Hargeisa and that travel outside the capital is difficult due to poor roads. Locals were wary of being photographed, and a possible visit to another town linked to Jewish history was abandoned due to time constraints.

The most surprising moment came after they returned to the United States, when Israel announced its recognition of Somaliland. Rubin said a local guide had mentioned the possibility, but they had not taken it seriously. “Honestly, that was the first time we heard Israel might recognize Somaliland,” he said.

Even after the printing, fear lingered. “Somalia or Somaliland is not a place you want to get involved with,” they said. The printers themselves were friendly, Rubin noted, but deeply concerned about potential consequences. “The punishment for anything connected to Judaism, especially publishing something like the Tanya, could be severe,” he said, adding that Israel’s recognition might now lead to more positive attitudes toward Jews.