As part of the dramatic changes the West Bank has undergone in recent years, particularly in the expansion of settlements, another significant shift is taking place in the field of archaeology. “Judea and Samaria are changing their face in the archaeological realm and the world of antiquities,” says Eyal Freiman, 41, an archaeologist and deputy head of the Civil Administration’s Staff Office for Archaeology unit. Freiman has served in the Civil Administration’s archaeology unit for more than 15 years and has witnessed firsthand the dramatic transformation that has gained momentum in recent years.

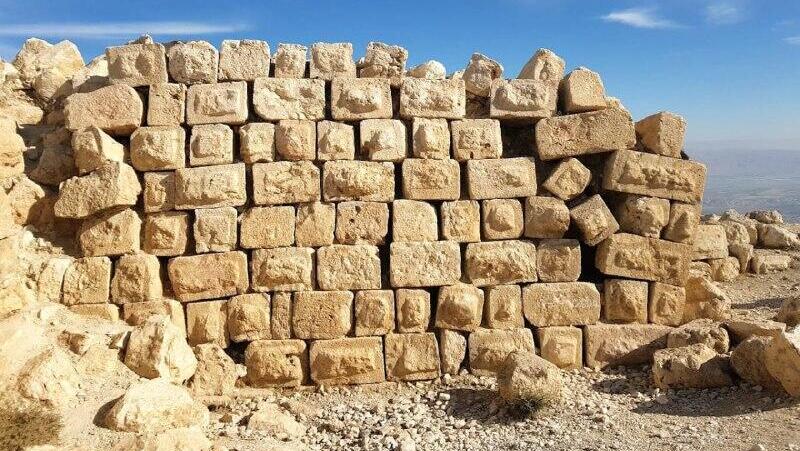

Sartaba housed a Hasmonean palace and later a Roman fortress, and is now being excavated

(Video: Civil Administration)

In 2010, the Israeli government adopted a decision to strengthen the enforcement and protection of antiquities in the West Bank, but it was an initial move with limited budgets and minimal attention from the military and government ministries. In July 2023, nearly a year after the current government was formed, a new government decision approved a multi-year plan to combat the destruction of antiquities and heritage sites in the West Bank. The decision, initiated by Heritage Minister Rabbi Amichai Eliyahu, Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich and Tourism Minister Haim Katz, allocated 120 million shekels over three years. The new budget fundamentally changed the work of the archaeology unit.

“There’s a story from the past that explains the change very well,” Freiman says. “As an archaeologist in the unit, one of my roles is to protect the land and the antiquities. I complained to my superiors that I couldn’t reach a site in Area C near al-Bireh east of Ramallah. It’s an Iron Age site from the First Temple period, and Palestinians had built a playground around it, so I couldn’t get there to ensure its protection. The answer I received was that it wasn’t possible to reach the site, so the system simply gave up on it. Today, we would never give up. Any place I want to excavate, I excavate.”

Heritage Minister Rabbi Amichai Eliyahu is one of the architects of the multi-year funding plan. “After decades in which attempts were made to erase the connection between the people and its land, we are restoring the true map of the Land of Israel," he said. "The future of our state depends on two arenas, the security arena and the consciousness arena. In this arena, the heritage sites of the West Bank are our vital asset. Over the past three years, we have worked to bring significant investments to archaeological sites. The dedicated teams of the Civil Administration’s unit are engaged in a national mission, uncovering our ownership of this land and passing on the memory to young people. This is an investment in the Jewish identity of future generations.”

Freiman himself is not a political figure. He and his team are focused on ancient finds, excavations and science, but they also understand that the government’s transformation beyond the Green Line affects not only the future, but also the past. A rare look into the Civil Administration’s archaeology unit reveals a fundamental shift in its outlook, resources, authority and findings. The unit’s budget has more than doubled, and it is simultaneously operating several large-scale projects from Hebron in the south, through Gush Etzion and Binyamin, to northern Samaria.

7 View gallery

Eyal Freiman, 41, an archaeologist and deputy head of the Civil Administration’s Staff Office for Archaeology unit

(Photo: Yariv Katz)

According to Heritage Ministry data, 3,064 Jewish heritage sites are scattered across the West Bank, 2,542 of them in Area C, under Israeli security and civil control. One-third of all sites, 1,150, have been damaged over the years by Palestinians.

At the same time, the path was paved by Benjamin Har-Even, the Civil Administration’s Staff Officer for Archaeology, who through extensive activity succeeded in motivating decision-makers to pursue legislative changes. These changes primarily transferred administrative and criminal enforcement powers to unit employees.

“Four years ago, we were a unit of fewer than 20 people responsible for all of Judea and Samaria,” Freiman said. “Fewer researchers conducted research because they were afraid to reach sites in Judea and Samaria. In addition, almost no universities excavated with us. Today, there are extensive excavation partnerships in Judea and Samaria with Bar-Ilan University, Tel Aviv University, Ariel University and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.”

Freiman also described the reinforcement of enforcement efforts against the Palestinian antiquities market. “In the past, the unit’s enforcement capabilities were extremely limited. There was only one ‘antiquities looting inspector’ for all of Judea and Samaria. Today there is an entire department dealing with enforcement, investigations and intelligence, staffed by 10 people and a lawyer who serves as a military prosecutor. Today it is possible to file indictments against Palestinians who looted or damaged antiquities in Judea and Samaria, including enforcement in Areas B and C.”

7 View gallery

Hyrcania, one of the Hasmonean fortresses in the Judean Desert

(Photo: Civil Administration)

The archaeology unit itself is composed of several departments: an excavations department responsible for rescue excavations; a statutory department responsible for archaeological surveys; a special investigations unit; a planning department responsible for preparing and overseeing plans to develop and make antiquities sites accessible to the public; a documentation department; and a curatorial department. About 400,000 artifacts have been discovered at archaeological sites across the West Bank and are stored in Civil Administration warehouses. The artifacts are not yet on public display.

Inspectors from the unit conduct active excavations and preservation work throughout the West Bank. Among the sites is Sartaba, in the Jordan Valley, located on the region’s most prominent peak, where an access route to the excavation site has already been opened. Sartaba housed a Hasmonean palace and later a Roman fortress, and is now being excavated after 30 years without research.

Another site is Hyrcania, one of the Hasmonean fortresses in the Judean Desert, which stood abandoned until recent years. The Civil Administration’s archaeology unit, in cooperation with the Hebrew University and under the auspices of the Heritage Ministry, began excavating the site, paving access roads and preparing a hiking route.

7 View gallery

Antiquities at Sebastia National Park

(Photo: Moti Sheffi, Israel Nature and Parks Authority)

Sebastia, a site that had not been excavated for 100 years and stood desolate, also has seen a revival, including renewed excavations at its entrance and the exposure of a southern wall previously unknown. Sebastia is a significant site and, as part of the excavation and preservation efforts, about 1,800 dunams were temporarily expropriated from Palestinians for several years due to antiquities damage and the need to preserve archaeological treasures.

The unit is also excavating Tel Rumeida, developing and exposing ancient Hebron, while planning preservation alongside the needs of community development near a Palestinian residential area. Additional work is being carried out in other locations in Binyamin and Gush Etzion.

For the archaeologists, the fieldwork and uncovering ancient findings from Jewish history are central. They also work to preserve national treasures located at archaeological sites throughout the West Bank. However, the sweeping changes the region is undergoing in security, construction and legal spheres related to settlement expansion do not bypass archaeological sites.

The link between settlement developments and archaeological considerations is evident in nearly every arena. For example, approval of the planned community of Mount Ebal, still unbuilt and located in Area C in northern Samaria, is taking place just one kilometer from the altar of Joshua son of Nun, located in Area B and vandalized several times in the past by Palestinians. Construction plans in the area have been stalled in part due to the need to protect the archaeological site.

Another example is Sebastia, currently in advanced excavation stages, not far from the recently approved settlement of Homesh. A series of government decisions, including archaeological aspects, are forming a broader picture of settlers’ return to northern Samaria communities evacuated under the disengagement plan, including Sa-Nur, Ganim and Kadim. Several archaeological sites are also located near Jenin, where researchers hope to expand activity in the future.

Researchers also report damage to archaeological sites, though not extensive, resulting from the surge in agricultural outposts in the West Bank. Initially, the phenomenon was not coordinated, leading settlers to establish farms using heavy equipment that damaged antiquities. The Civil Administration now says coordination with the archaeology unit has improved, creating a more workable environment.

The unit has also encountered academic boycotts from Israel and abroad regarding archaeological research in the West Bank. “Since the 1990s, a consensus has formed in academia in Israel and worldwide that archaeological research in the West Bank is illegitimate and contrary to international law," Freiman explained. "Many researchers use archaeological findings to advance political agendas. Researchers didn’t come, creating a severe research vacuum. Part of the change was developing research in the West Bank in cooperation with universities. The Heritage Ministry is investing money in this.”

He added: “A year ago, we organized the first state-sponsored conference of its kind at the Dan Hotel in Jerusalem, presenting research by Israeli and international scholars who studied findings in Judea and Samaria. One Italian researcher faced disciplinary proceedings at his workplace after participating in the conference. Another Irish researcher had his research canceled because he attended. This phenomenon existed, and since the war began, it has intensified.”

Freiman concluded that “Judea and Samaria contain significant national and historical assets for the State of Israel. We must preserve antiquities as much as possible while carrying out a range of activities on the ground to prevent damage from uncoordinated construction.”

Asked whether archaeology in the West Bank is part of an attempt by the settlement movement to create facts on the ground, Freiman replied: “I look only at archaeology. Ultimately, I am an archaeologist, and I understand the importance of archaeological treasures and assets to our heritage as a people. Archaeology has always been a tool for interpretation, and people still use it that way. Every day, I see the unit’s work as my own piece of paradise, and my goal is to preserve and protect the antiquities of Judea and Samaria. Today, we have better tools and capabilities to do that.”