There is something in the quiet confidence of Ayelet Shabo that tells the story of a woman who has come a long way. So far, in fact that people around her are convinced she grew up in a comfortable, stable home. They do not know that she entered the world of design from a place marked by deep personal rupture, one that offers little space for dreams or ambition.

She was 7 when a social worker escorted her to a children’s rehabilitation home run by the Mally organization, where she grew up. She was a teenager visiting her father in prison, a divorced 23-year-old with a baby who refused to give up on studying architecture, and a woman who built for herself a new life, a family and a profession.

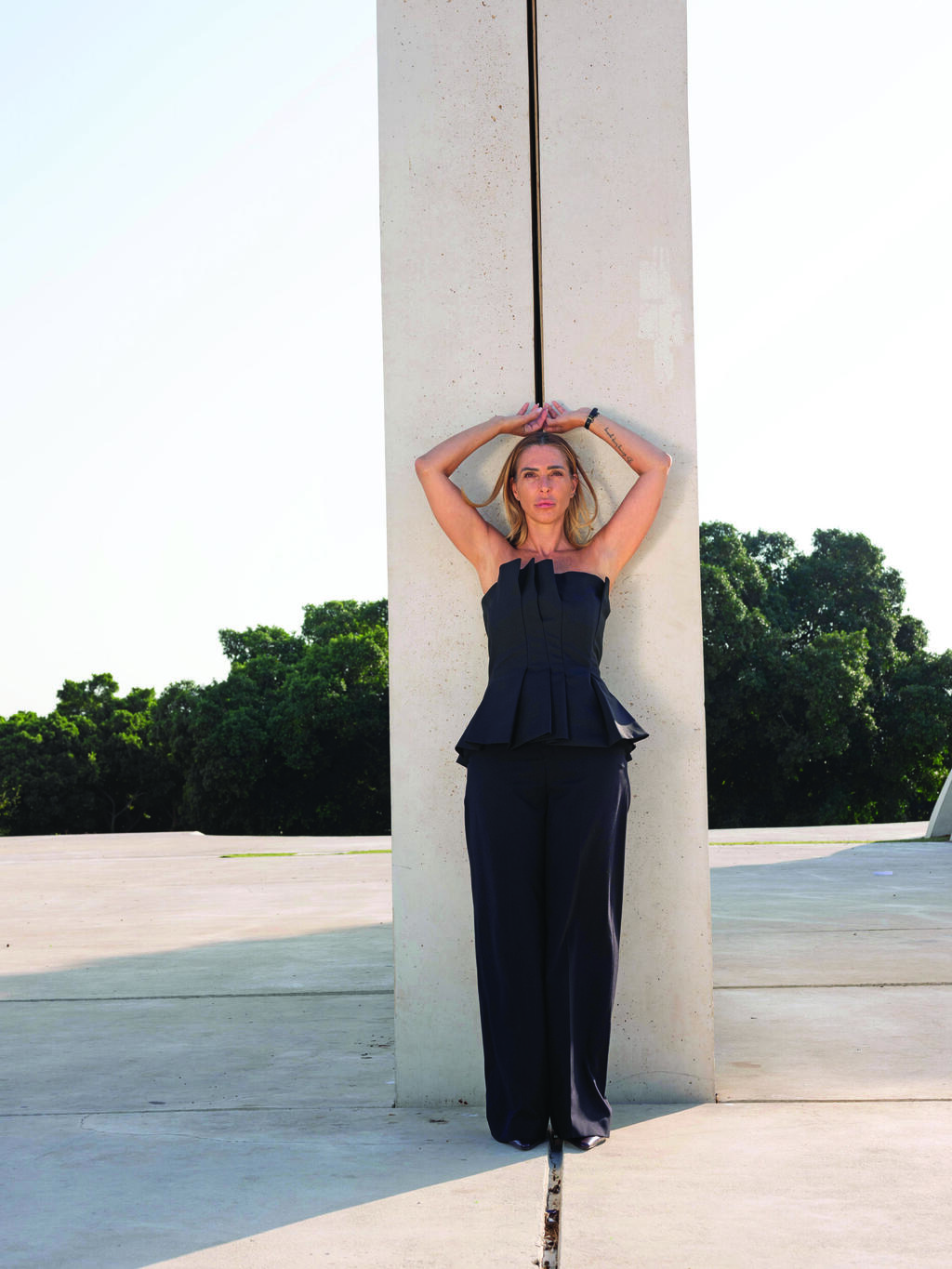

6 View gallery

'I want to help children understand that they have power, to tell them there is no glass ceiling'

(Photo: Yuval Chen)

Today, at 47, Shabo is returning to the place where she grew up, this time by choice, to meet children who are exactly where she once was. “If my words make even one child understand that they have a chance, I’ve done my part,” she says.

She was in second grade when she arrived there. So young, yet old enough to grasp everything. Many of Shabo’s memories are fragmented, entire years erased. “It’s a kind of defense or survival mechanism,” she explains. But the day she was sent to the boarding school is etched clearly in her mind.

She remembers her mother putting her in the car without any preparation and driving from her hometown of Netanya to Afula in the north. “We arrived, and someone greeted me, probably a social worker,” she recalls. “It was a pastoral, beautiful place with ten villas. I walked into one of them, and there were ten children I didn’t know, and a couple with children of their own who were supposed to raise us. The only mother I knew drove away, and there was no one to talk to. I cried and wanted my mother. The house manager, Yehudit, hugged me and said she was there for me. But I was only seven. It didn’t matter if she was good or not. I wanted my mother.”

Living in autopilot mode

That first day was the first and last time she cried there. “In one day, I was cut off from everything familiar,” she says. “They put me in a room with a girl I didn’t know. Even though I felt God holding my hand, I was afraid to sleep. The next morning, I woke up among strangers. There was this long table filled with sliced bread and spreads, and I was supposed to make myself a sandwich and go to a school I didn’t know."

In an unconscious decision, she shut down emotionally. “I put up a wall so I wouldn’t feel,” she says. “I started living in autopilot mode. I did everything I was told. No crying, no shouting, no questions. I understood there was no point in crying. I just had to keep going.”

Did you ever ask your mother why she sent you to a boarding school?

"No. I can only guess,” she says. “She wasn’t a bad mother. She was a beautiful, kind woman who had a very hard life. When my younger brother was born, my parents were already separated. My father wasn’t normative. He made my mother's life miserable. There was alcohol, betrayals, and he would go in and out of prison. We had no money. She didn’t work and wasn’t financially independent, and she couldn't support us. She married a man she was completely dependent on, and even later, when she had partners, she always needed a man to take care of her.

After her mother and partner divorced, all three children were sent to boarding school. “I think she believed that once she got back on her feet, she would bring us home,” Shabo says. “My brother, who is two years older than me, left the boarding school of his own accord and went back home, and so did my younger brother. But I was the compliant child. I did what I was told.”

Did you ever ask to go back home?

“I didn’t think it was an option,” she says. "My mother never told me to come back, and it never occurred to me that I could say I wanted to return. I created a fantasy world because I had to survive. On the surface, everything was fine, even pleasant, compared to the home I came from. There was hot food, a clean bed, clothes, activities and friends. You don’t think about whether you’re happy or not. But something is always missing. You don’t have a real home or roots. You don’t know how to belong."

Her deepest bond was with her father. “We found each other,” she says. “He was in prison, I was in boarding school. Two lost souls. I felt we were in the same place. I wrote him letters and he wrote back. I visited him regularly. There wasn’t a prison I didn’t know as a child,” she says.

What was he imprisoned for?

"I don't know. That’s a question I still need to check,” she says.

At times, he was her only safe place, even though he could not truly be there for her. “Once I ran away from the boarding school and went to him after he was released,” she recalls. “He bought me sweets and took me back to the boarding school by bus. There was tenderness in him. He loved me. My mother loved me too, but I felt that she was the one who sent me away, not him."

Are you angry at her?

"For years, I blamed myself. I thought maybe I had done something wrong and that's why they sent me to boarding school,” she says. “That’s one reason I became such an obedient child. Today, I cannot be angry at a woman who was broken herself. I understand her. She did what she could with the tools she had. It was a different generation, a different way of thinking."

Did you talk to your brothers about what you went through?

“At first, there was a lot of pain. My brothers were at home, so why wasn’t I there? When I was nine, my mother became pregnant by someone else, and I have a younger sister, now 38. She is the greatest gift I could have received in my life.

"In one of our conversations, I told her how lucky she was to have our mother caring for her and to grow up in what seemed like a family idyll. She told me, ‘You have no idea how lucky you are, how much you were spared.’ She said there were days when there was no food in the house, days when no one came to pick her up from school. When I came home from boarding school for visits, there was always food and cakes."

First love

When her mother died of cancer, Shabo was 21. “They say she could have been saved, but life was too heavy for her,” she says. “She was tired. We barely had time to say goodbye. Shortly before she died, she told me she was sick."

Now she feels compassion for the woman she never truly knew. “I understand how much she suffered,” she says. “She wanted to be a nurse. She dreamed of a different life."

After finishing sixth grade, Shabo moved from the Mally boarding school to the religious kibbutz Ein Tzurim as a day student. “It’s a wonderful place, with lawns and open spaces,” she says. “There were 30 to 40 of us doing everything together: studying, working, eating, sleeping. Like in a boarding school, but more independent.”

After high school, she served in the army and later married her first partner. At 22, she became a mother to a son, now 24. “He’s my heart,” she says. “No one in the world knows my story like he does.

“I met my husband when I was 17,” she says. “He was 10 years older than me, an amazing man, a dean’s list student. But we didn’t speak the same language. I couldn’t give him what he needed, the love he was looking for."

At 23, with a six-month-old baby, she left. “I had nothing,” she recalls. “I moved in with my father, along with my son. My father had gone through rehabilitation and become a different person. I knew one thing: no one was going to tell me how to live my life. I was living for myself, doing only what was good for me.”

The marriage ended when she was 23 and her son was six months old. “I had nothing,” she says. “I moved in with my father, who had gone through rehabilitation and become a different person. I knew one thing: no one would tell me how to live.”

She enrolled in architectural engineering studies at Ruppin Academic Center. Days ran from early morning until evening, followed by nights of coursework. “My son spent a lot of time with his father and with my father. There were times when I would reach out to him and he didn’t want to come", she recalls. “It was painful. There were days filled with tears, but I tried to shut down every emotion, and if anyone knew how to do that, it was me. But I told myself, 'Don't let emotions stop you'. I was focused on one goal: to finish my studies, to earn a degree, so I could support myself and my child. I could have chosen a simple life, but I wanted more."

Years later, she remarried and entered a framework she had never known: family life. “My second husband had an incredible mother. I felt she was like a mother to me. I loved her deeply. With her, I felt at home for the first time, and in her presence I allowed myself to be who I really was.”

The couple has three children, now 13, 10 and 8. “I look at my eight-year-old and can’t believe that at his age I was already in a boarding school, alone,” she says.

About six years ago, shortly after her beloved mother-in-law died, the couple divorced. “If it had been up to me, I wouldn’t have divorced,” she admits. After the divorce, she moved into an apartment she had purchased in Netanya, a moment that proved pivotal for her.

“When I walked in for the first time, I couldn’t stop crying. I have a home I bought on my own, through hard work. Every time I think about it, I’m overwhelmed. The fact that I can buy myself whatever I want, that I don’t need gifts from anyone. It’s a kind of strength that’s hard to put into words. There isn’t a morning when I don’t wake up and begin with gratitude for what I have.”

Today, Shevo runs an independent architecture studio with a long client list, including public figures.

She recently completed building a complex of 10 villas in the community of Carmit and is now working on a premium hotel project in Panama, essentially a six-bedroom private residence. “I always want more, to prove to myself that I’m good, that I can do it,” she says. “My eldest son always tells me that even if I reach Everest, I’ll be looking for the next mountain."

Her design style, she says, is rooted in the kibbutz. “Bringing the outside in, bringing in air, nature and light. My profession is my mission. As a child, I didn’t have a home, and today I repair homes for people, building spaces that truly suit them.”

Recently, Shabo returned to visit the children’s home where she grew up, run by the Mally organization. A 15-year-old girl gave her a tour of the village. “I asked her, ‘What do you want to be when you grow up?’ She didn’t know how to answer. She was stunned by the question,” Shabo says. “I told her, ‘You deserve to dream,’ and she started crying. I understood her. That was exactly where I once was. You don’t allow yourself to think that you deserve anything."

In partnership with Psagot Winery, she launched a community engagement project. The first initiative was renovating the home at that same boarding school. “When I walked in for the first time, I couldn’t stop crying. That was my room, my bed. It was an incredible closure,” she says. “In retrospect, that place gave me the strongest foundations, even if at the time I couldn’t appreciate it. I remember the sign that hung there, ‘Educate a child according to his way.’ I looked at that sign every day. That’s how I raise my children today, and that’s how I conduct myself in the world.”

Soon, she will visit another of the organization’s family homes to meet the children and share her life story in the hope that it will help them. “I want to show them that success is possible, to give them strength and motivation, and to tell them there is no glass ceiling. You are capable, and you can do it.”

Looking at her life today, she no longer feels pity for the girl she once was. “I was dealt certain cards. Not good ones, not bad ones. Just cards,” she says. “And I chose what to do with them.”

15 children’s villages providing a home to those in need

Mally (Hamifal Le’Hachsharat Yaldei Israel) is an educational and rehabilitating organization that was founded 80 years ago by the late Mrs. Recha Friar, an Israel Prize winner. As of today, there are 15 children's villages and homes throughout Israel, welcoming around 940 children aged 6 to 18 who were removed from their homes under various circumstances.

The villages are based on an educational family-cell model in which 10 to 12 children live together in a home with a married couple and their own children, functioning as a family in every sense.

This framework provides valuable experience of growth and development in a setting that most closely resembles a true home and family. The house parents serve as available, supportive and nurturing parental figures.

The children living in the villages are integrated into community educational frameworks and benefit from a wide range of therapeutic services, tutoring and enrichment extra-curricular activities in the afternoons.