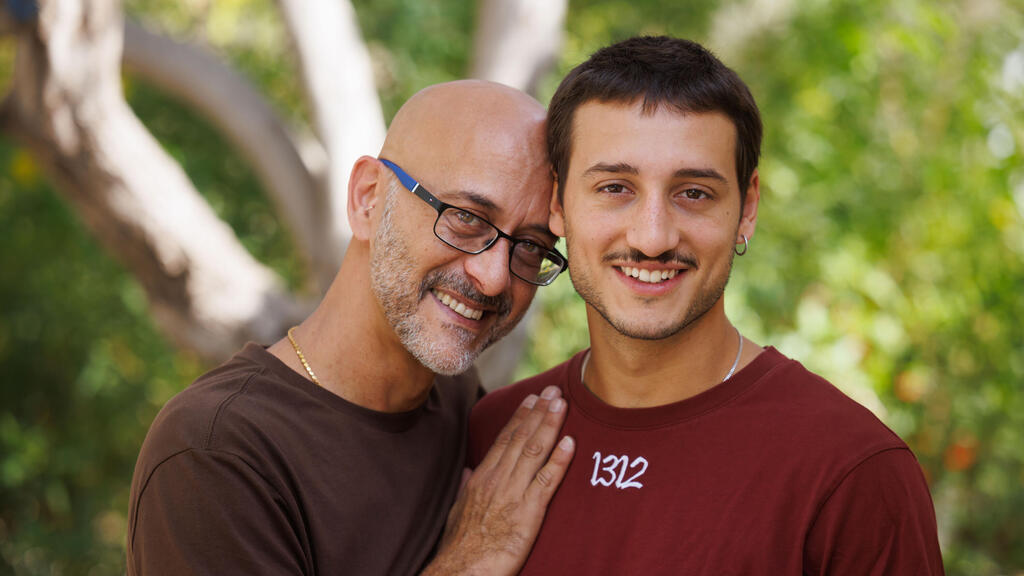

For nearly two years and four months, since his son Liam Or was abducted from his home at Kibbutz Re’im in the October 7 attack, and even after he was released from Hamas captivity, Ramzy Nassar chose to stand aside. Not in front of television cameras. Not in newspaper interviews. Immediately after the kidnapping, his son’s name was changed, Ramzy’s own identity was obscured, and the silence became a strategic decision — cold, calculated, life-saving.

Ramzy — Israeli, Arab, Muslim, a kibbutz member — knew that the reality in which his son was being held in Gaza could not tolerate additional layers of complexity. Now, after time has passed and the price has already been paid, he is choosing for the first time to break his silence and tell his story: the trauma of the massacre, the childhood that shaped him, racism, stereotypes, and what it means to give up your voice in an attempt to save your child.

Hours after learning that his 18-year-old son had been abducted, an unusual decision was made in the Or-Nassar household: to erase Liam’s second family name. On the protocol sheet prepared by the family’s ad hoc crisis command center, it was written: “Liam Or.” Beside it, a single, firm line crossed out the name “Nassar.” Not a mistake. Not confusion. A conscious decision. A few lines below it was written: “Ramzy not up front. Ramzy Nassar understood that in order not to harm his son’s chances of returning home, it was better that the public — and Hamas in particular — not know his background.

The decision: zero communication on my part

“After we were evacuated from the kibbutz, we went to friends’ apartment in Tel Aviv,” Ramzy recalls. “That was also the first time I cried after the insane 24 hours we had gone through. More friends arrived, and the command center was set up.”

At that stage, the family counted five missing people. “We knew Liam was kidnapped, that Dror and Yonat, Alma and Noam were missing or kidnapped,” he says. (It later emerged that Yonat was murdered, Dror was murdered and his body abducted, and the children Alma and Noam were kidnapped alive) “Then the discussion began: What do we do now? Goals, means, stages. A friend took a sheet of paper and started writing a protocol. I understood that at this stage there was no one to talk to — not the army, not the police. The working assumption was that we were alone.

“I immediately knew there was another story here, another factor — my background. I was not prepared to risk Liam or to attach to that asset additional traits and value in their eyes. The decision was zero communication on my part, and to wrap Liam within the Or family framework, not on his own.”

So instead of shouting, silence was chosen. How did that feel?

“To be honest, I left emotion behind earlier, in the car. I thought and acted only out of cold, painful considerations. Zero room for emotion, only logic. There simply wasn’t space for it. There is one goal, and all means are legitimate. No one can tell me whether I did right or wrong. Everything was right, because I did everything to bring my child back. I didn’t want to divert attention to myself. I wanted to focus only on him.”

Another decision made for the same reason of obscuring identity was a formal name change. “We removed the name Nassar and left only ‘Liam Or.’ We created a precedent in the State of Israel — changing the name of an adult not in his presence. That had never happened before. When Liam was released, at the hospital they gave him an ID card and he was surprised to discover the name change. I explained why we did it. He understood, but asked to change it back. That same day it was corrected.”

So you distanced yourself, your identity.

“It hurt a lot. Very much. It made me deeply sad that I had to be silent because of my identity, my background, within the country I live in, out of fear that it would harm my son, there in Gaza or here in Israel. It made me ask: What reality am I even living in? Changing the family name was a very painful decision, but every decision was made solely to protect Liam.”

You mean considerations of danger and security.

“Yes. The thought was that if Hamas knew, it could harm Liam. It wouldn’t have been received well on the other side that his father is a Muslim married to a Jewish woman, even though Islam does not prohibit this. The child could have been considered a traitor, the son of a traitor. There was fear it would lead to further abuse, to harsh interrogations.

“What did happen, by the way, were interrogations, and Liam told them I was Druze — my father’s previous background. We also didn’t want them to assign him ‘higher value,’ to hold him longer, if here in Israel it turned into some major media event.

“Even as it was, the knowledge that your son is in the hands of an enemy, of a terrorist organization that does not operate according to any rules or law, that can do whatever it wants to him, is unbearable. The daily worry was enormous, the anxiety. And there was also fear he would be hurt by our bombings, by the army. There was also concern they might try to reach my parents, for the same reasons, that information would be exposed and someone would harm or take revenge on them.”

To understand the personal meaning of such an act — erasing a family name — it is worth returning to a conversation we had long before the interviews for this article began. “My name, Ramzy Nassar, is not a technical detail. It is identity,” Ramzy said then. “The way it is pronounced matters to me — the slowness, the precision, the correct spelling, without adding or subtracting. My whole life people have gotten my name wrong — in Hebrew, in English, in documents, in schools, even today. They swap letters, add an ‘a’ that doesn’t exist, confuse completely different names in Arabic and in meaning. It sounds small, but these are two different names, two different meanings.

“For me, insisting on the name is basic respect, because a name is the simplest way to connect with a person. When someone says your name, you listen. We all like to hear our name. It’s important to me to be called correctly, because that’s who I am.”

And “who I am,” in Ramzy’s case, is many things. “I’m a father to Liam, Guy and Rani. I’m Israeli. I’m Arab. I’m Muslim. I’m a kibbutz member. I’m a friend. I love parties — that’s where I feel free. From a young age I felt that in this party community you can express yourself. It’s a nonjudgmental place, a place of expression, because you can’t always express everything in words, and when the words end the body starts speaking — in a hug, in movement, in dance. Everyone is equal in front of the speakers. Your background, your job — they don’t matter.”

“The boy turned to me and asked, ‘What’s your name?’ I answered, ‘Ramzy.’ He said, ‘No, you’re Arab.’ I didn’t understand what he wanted from me. What was wrong with me? What was the problem? He asked, ‘How do I know you’re a good Arab, that you won’t stab me with a knife?’ I was in shock. It stayed with me as the first moment when I felt something was wrong with me, but fairly quickly I understood: I’m completely fine.”

The abduction and the release: ‘The whole world stopped'

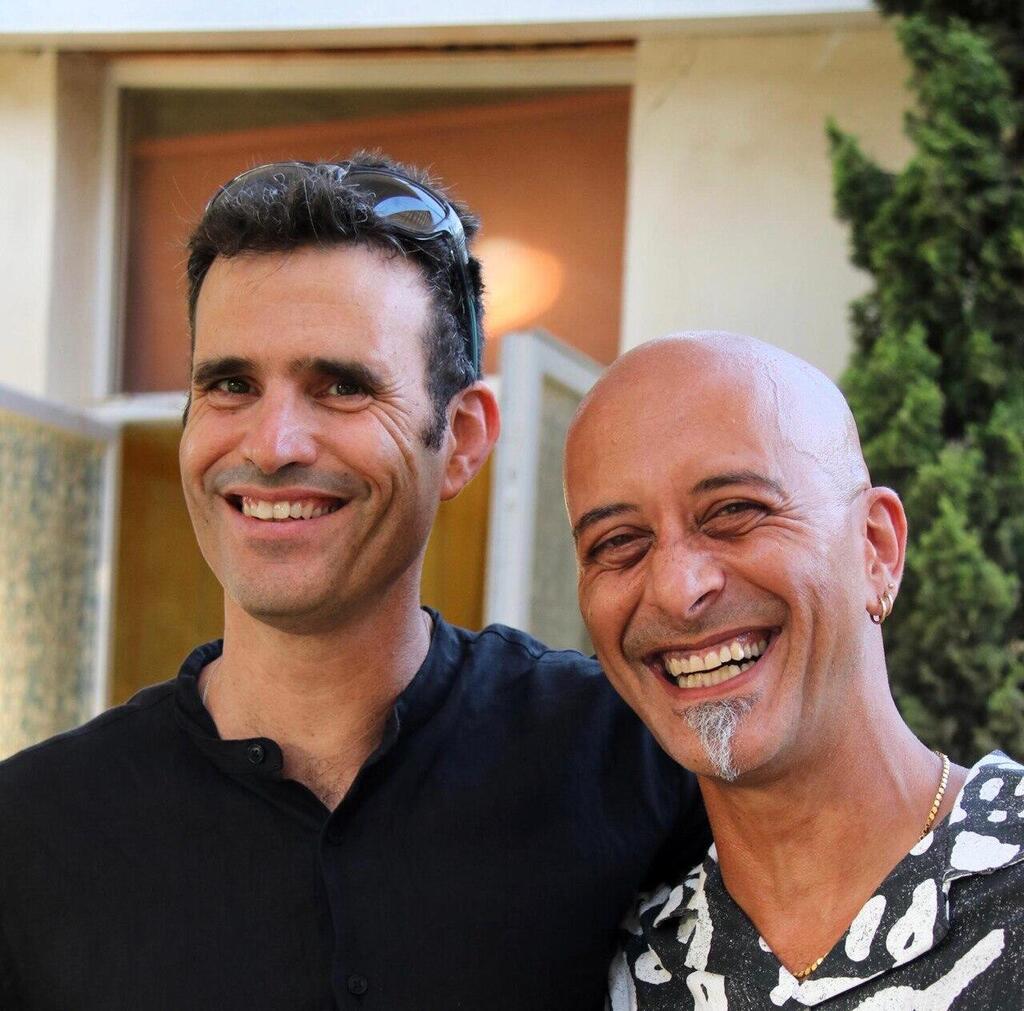

Even on the day of the brutal surprise attack, Ramzy was supposed to attend the Nova music festival, which was held adjacent to his home. At the previous party held there, produced by Unity, he had attended. “I’ve been part of this community for decades, and I wanted to see a performance by an artist I love from Sweden. My brother-in-law Dror was there with friends from Kibbutz Be’eri. That was the last time I saw him.

“At the party I met friends and offered that they sleep at our house, because they planned to go to Nova later. And that’s what happened. I planned to return to the party on Saturday morning. I slept on the couch, and at 6:30 a.m. I woke up to the sounds of interceptions. On the screen, long lines of alerts were running. I thought it was a malfunction. Outside, wherever I looked, I saw streaks of smoke across the sky, launches going out in every direction.”

Liam was living at the time in the young adults’ neighborhood of the kibbutz, a few dozen meters from his parents’ home. “I called him, he didn’t answer. I woke the kids and Dana and we went into the safe room. I called the friends who had stayed with us overnight, heard shouting, and told them to come back to us. They arrived and joined us in the safe room.

"I called Liam again, woke him. In the kibbutz WhatsApp group they wrote that there was concern about terrorists infiltrating, and shots were already being heard. I called Liam, who was on hold, speaking with his partner. We texted, and he said he heard people outside, footsteps, shouting, bursts of gunfire. I wrote to him about the infiltration concern, asked him to stay in the safe room. He wrote to me, ‘Dad, I’m scared.’”

At 8 a.m., Ramzy called Liam again. This time there was no answer. “I texted him several times to answer. There was no response. I checked his phone’s location. It was still in his room. We received messages about terrorists in homes, about fires. The couple of friends with us in the safe room were getting horrific updates from Nova. On television we saw the pickup trucks in Sderot. We didn’t understand. We didn’t believe it. We waited for the army in a helplessness that’s hard to describe — and we had no contact with Liam."

“In the kibbutz group they wrote that terrorists were concentrating in the young adults’ neighborhood. The day went on. No army. No communication with the child, not with Yonat and Dror in Be’eri either. The kibbutz’s standby security squad — seven heroes — fought the terrorists until the afternoon, when army and police forces arrived. Liam’s partner called crying and said a kid from their grade had sent her a picture of Liam. She was in shock and couldn’t send it to me. I called that kid and asked for the photo.

“I looked at it: Liam, wearing only boxers, tied up in a tunnel. One part of my head said, ‘That’s Liam, your son.’ Another part said, ‘It’s fake. It’s impossible.’ But my heart said: Ramzy, you know this is your child. Guy, Liam’s brother, was next to me. He saw the picture and screamed a scream that still rings in my ears.

"You have to understand, the three brothers are so close. Brothers to be proud of. They admire each other. Together they are a force, an empire. I grabbed him, looked at him and said, ‘Guy — he’s alive. And he will come back.’ We went into the safe room and I told Dana and Rani: ‘Liam was kidnapped.’ Dana, in panic, said, ‘They took my child, they took him.’ We sat there, not knowing what to do. Evening came. A tank entered the kibbutz to blow up a house in Liam’s neighborhood where terrorists had barricaded themselves. Soldiers went from house to house. We were exhausted, not knowing who to talk to.

“Before we were evacuated, I went to Liam’s room to see, to understand what had happened there. On the short way there lay the bodies of terrorists, grenades scattered around. The clinic was broken, shattered. In his house I saw the doorframe ripped out. The door open. Inside, chaos. Bullet holes in the wall.”

On November 29, 2023, after 54 days in Gaza, Liam was released as part of the first deal. “It’s hard to explain the feelings on the day of the release,” Ramzy recalls. “The closest thing might be the birth of a child. The days leading up to the release were nerve-racking, extremely charged with expectations, with disappointments — a real roller coaster. At dawn we got a call updating us: ‘He’s on the list.’ The release process itself was very long. I waited for a picture, something tangible, to know the child was OK. I remember seeing a photo of him on a minibus, nodding to a soldier who was there and moving on. Nothing compares to that.

“When we finally met, I ran to him, he ran to me, we hugged. The first thing Liam said to me was, ‘I’m OK, Dad, I’m OK.’ To hear him say that? A dream. I felt the whole world stop. Just to feel him, to smell him again — it’s insane. That was the moment I started breathing again.”

How is Liam coping today, with the reality after captivity?

“Between the child who was kidnapped and the young man who returned from captivity, there is an enormous difference. It’s not the same person. There are the traits that protected him and allowed him to survive, but he changed, and that’s expected and understandable. After he returned there was a long period of adjustment and difficulty, and maybe in some place, even though he returned physically, in certain areas he hasn’t fully returned yet.

“Today he travels a lot, does sports. One of the things he clings to as an anchor is his membership in Hapoel Tel Aviv, the soccer team he supports. It’s a place that unites everyone, where everyone is equal. He invests time and effort in it — in fan activities, going to games. He returned to Kibbutz Re’im and wants to settle there. He has dreams he wants to realize and develop. He does what’s good for him, what makes him smile.”

'How do I know you’re a good Arab?'

Ramzy was born in Misgav Ladach, in Jerusalem’s German Colony neighborhood, in August 1975. Five years later his sister Rena was born. Today she lives in the United States with her three children. He spent his childhood and adolescence in Jerusalem, where he lived until age 19. The family moved between neighborhoods — the German Colony, Ramat Eshkol, Beit Hanina and Givat Mordechai. He attended a Na’amat kindergarten in Neve Yaakov, and then from first through 12th grade studied at the Anglican School in the city, an institution owned by the Anglican Church, housed in a historic building more than 100 years old.

“We had weekly hours of Jerusalem studies,” he recalls. “We went to the Jewish Quarter, the Christian Quarter, the Muslim Quarter, the walls. We learned about the Byzantines, about Christianity, but also about the entire history of the city, all the colors of the spectrum. We learned about the endless conquests, about the amount of blood spilled here and the land that continues to absorb it.”

“I come in as an underdog, a member of a minority. And the nature of minorities, as described in sociology and anthropology books, is that they carry a drive to prove they are better. So yes, that pushed me to reach places, roles, things that were demanded of me or that I demanded of myself. Maybe to prove I’m better — I’m not what you think, but more than what you think, and better than you.”

“The period at the Anglican School was a cocoon of an international community, with many cultures and religions interwoven,” Ramzy continues. “The school absorbed children of U.N. employees, international agency staff, embassies and consulates, families who came on assignments to Israel from all over the world. I remember that during the Gulf War, for example, about 70% of the students left the country with their families, and only four or five students remained in the classrooms. We studied wearing gas masks, decorated them during lessons. Those moments created deep cohesion and a sense of partnership: Everyone is different, everyone comes from somewhere else — but everyone lives and studies together, dealing with the same reality.”

You’re describing an almost ideal world. When did you realize the outside reality could also be different?

“At the crude level of racism, my world was almost ideal. Truly. I was inside a very universal cocoon. At school, racism simply wasn’t an issue. If there was such behavior, something that humiliated or harmed a child’s dignity because of their background, skin color or language, there was punishment. Zero tolerance. They were willing to remove a child from the school and not readmit them over such an expression. Racism met me mainly outside school hours. Until then I had a protective, embracing framework, and then there was one moment when I understood that something was changing.”

What was that moment?

“It happened at a summer job. I was 14. My aunt found me work at the central Postal Bank in Jerusalem, in Givat Shaul. Several kids my age worked there together, sorting mail. I was the only Arab. I would arrive in the morning, stop at Angel Bakery, buy a roll and chocolate milk and start working. One day, all the kids were talking and getting to know each other. One of them turned to me and asked, ‘What’s your name?’ I answered, ‘Ramzy.’ He looked at me and said, ‘No way, you’re Arab.’ I didn’t understand what he wanted from me. What was wrong with me? What was the problem? He asked, ‘How do I know you’re a good Arab, that you won’t stab me with a knife?’

“I was in shock. That stayed with me as the first moment when something suddenly felt wrong about me. But pretty quickly I understood: I’m completely fine. The problem isn’t with me. That moment exposed me to the conflict we live in here. One state, we’re all citizens, but there is history, and there is baggage.”

“Yes, I’m identified with the Muslim religion. Yes, it’s part of me, but it doesn’t define me. Religion and faith are very personal things. In the end, we’re all human beings. There is a great deal of racism in this country, between everyone and everyone. When you understand that, it’s easier to cope — even though the comparison here in Israel is fundamentally flawed, because Judaism is a religion and Arabness is an origin.”

And how did that baggage affect the rest of your life?

“It didn’t become the central thing in my life. I didn’t let it manage me. I know who I am, I know where I come from. I understood that people like to categorize, to live with stereotypes. Like Russian immigration — a different name, a different language, and immediately labels: ‘vodka,’ ‘don’t like to work.’ The moment you speak with someone face to face, identity starts to define them. I’m identified with the Muslim religion, yes. It’s part of me, but it’s not what defines me. Religion, faith — those are very personal things. In the end, we’re all human beings.

“There’s a lot of racism in this country, between everyone and everyone. When you understand that, it’s easier to cope. Even though the comparison here in Israel is fundamentally flawed, because Judaism is a religion and Arabness is an origin. And yes, it affected my life. Look, I come as an underdog, a minority member. And the nature of minorities, as described in sociology and anthropology books, is that they always have the drive to prove they’re better. So yes, it motivated me to reach places, roles, things I was required to or demanded of myself. Maybe to prove I’m better — I’m not what you think, but more than what you think, and better than you.”

The culture and values in the Nassar household, he says, were those of a classic but progressive Arab-Muslim Jerusalemite society. It wasn’t a religious home. We didn’t go to the mosque every day and we didn’t live by decrees, but the customs of the Arab and Islamic world were present in the food, in the hospitality, in conduct. The best food in the world, classic Arab-Jerusalem cuisine, stuffed vegetables and home dishes and the hospitality: open, warm. We spoke mainly Arabic, but Hebrew and English were always present. We grew up with three languages. My sister and I will always speak first in English. Even if our parents wanted to speak between themselves so we wouldn’t understand, they had no such option, because we understood everything. At the same time, most of my Hebrew I learned only in high school. Before that it came from television and the neighborhood.”

I'm staying here

Since then, the world has changed from end to end, and Ramzy has been exposed to the complexity of Israeli society and the fragility of the sense of security. “Relationships, work, conversations — everything took on a different proportion,” Ramzy says. “Priorities are different. Part of the recovery process is creating a new routine, because a reality similar to what existed before will no longer exist. The conduct is different. The thinking is different. I can say that yes, the sense of security was pulled out from under my feet. And in Gaza we still have a hostage, Ran Gvili, but there is an attempt to find or create some kind of inner calm, at home, in the family, at work. In every area. There is a desire to enjoy things. Satisfaction becomes more important. We saw how uncertain tomorrow is, how many surprises the future holds.”

Ramzy met Dana, who would become the mother of his children, in Tel Aviv. For years he worked in television production. Dana had a catering company that supplied meals to crews, and that’s how they met. About a year after Liam was born, they decided to return to Kibbutz Re’im, where Dana was born and raised. We wanted the children to grow up in a values-based, supportive community, and it was one of the best decisions we made,” he says. “As a mixed couple, and in general. And today, even after everything we’ve been through, we’re here. I’m here. I’m staying.”